calsfoundation@cals.org

Dallas County

| Region: | Southwest |

| County Seat: | Fordyce |

| Established: | January 1, 1845 |

| Parent Counties: | Bradley, Clark |

| Population: | 6,482 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 667.32 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

6,877 |

8,283 |

5,707 |

6,505 |

9,296 |

11,518 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

12,621 |

14,424 |

14,671 |

14,471 |

12,416 |

10,522 |

10,022 |

10,515 |

9,614 |

9,210 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8,116 |

6,482 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

3,487 |

53.8% |

| African American |

2,592 |

40.0% |

| American Indian |

17 |

0.3% |

| Asian |

7 |

0.1% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

0 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

103 |

1.6% |

| Two or More Races |

276 |

4.3% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

201 |

3.1% |

| Population Density |

9.7 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$38,072 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015-2019) |

$20,517 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

14.7% |

|

Dallas County is a rural county, dominated in its early days by farming, mostly cotton, and then railroads and timber; these industries have accounted for the majority of economic sustenance for residents and landowners throughout its history. Many communities that exist in the county today owe at least some part of their development to the construction of either a nearby railroad, mill, or both.

Pre-European Exploration

Just prior to European exploration and settlement, Native American tribes, primarily Caddo and Quapaw, lived, traveled, and hunted in the area now known as Dallas County. Several sites identified as burial or other sacred sites have been identified in southwest Arkansas, and some were explored by archaeologists earlier in the twentieth century, including some in Dallas County.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

White settlement of the Ouachita River valley began as early as 1812. Very little settlement was in the area now known as Dallas County until 1840, but even those settlers were mostly farmers and their slaves. While agriculture has always been the primary concern of the county’s citizens, industry—such as sawmills, grist mills, flour mills, cotton gins, tanyards, blacksmith shops, and pottery producers—was also evident before the Civil War.

Pottery production was a particularly important industry in Dallas County starting in the 1840s. Several clay beds that provided suitable clay for pottery were available in the area. The earliest example of an organized commercial production of potters’ clay was established by Joseph and Nathaniel Bird in 1843. The Bird family was the most prominent in the industry and the youngest brother, William, eventually headed it. In the last years of the century, John C. Welch, a former apprentice to William Bird, was the sole owner and operator of a pottery production facility in the county. An apprentice of Welch, Lafayette Glass, would establish his own pottery-manufacturing concern, but he would eventually move his operation to Benton (Saline County) to establish the industry there.

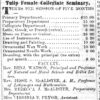

The first community to gain prominence in the area that is now Dallas County was Tulip. Previously named Brownville and then Smithville, after prominent early settlers and citizens, Tulip was located on the Chidester Stage route from Camden (Ouachita County) to Little Rock (Pulaski County) and boasted three different collegiate schools and a literary magazine during its heyday. The schools in the community included the Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary and the Arkansas Military Institute. By the time the county was created in 1845, Tulip was well established, but it was never incorporated and was never the seat of the county’s government.

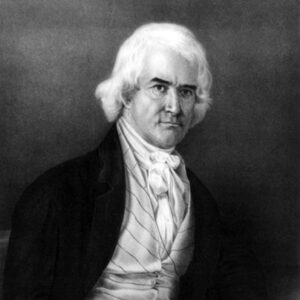

Dallas County was created on January 1, 1845, from parts of Bradley and Clark counties. It was named for George Mifflin Dallas, eleventh vice president of the United States. The town of Princeton was platted as the county seat of the newly formed county and, by 1850, rivaled Tulip as the economic and cultural center of the county, with its own academy and a prominent inn.

The first courthouse was a log structure built in 1846 on the east side of Princeton’s town square. Previous county business had been conducted in the home of a Mr. Watts, presumably Presley Watts, the first county clerk.

By 1850, the county had 256 slaveholders owning 2,542 slaves, mostly farming cotton and other crops. In 1852, the original log courthouse was replaced and paid for by a member of the Smith family. In 1855, Princeton was incorporated. By 1859, a map of Arkansas marked the communities of Tulip, Princeton, Fairview, Red Bird, and Chappell in Dallas County, although the communities of Holly Springs and Pine Grove, both settled around 1840, had been mentioned elsewhere in previous writings.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Represented by Robert Fuller at the 1861 Secession Convention, Dallas County had a white population of 4,788 along with 3,494 enslaved people. Fuller himself is recorded as a lawyer in the census, and he owned at least twenty-three enslaved people.

Roughly 500 farmsteads, houses, churches, and schools dotted a Civil War map of Dallas County, most disappearing during or shortly after the war. Few structures were actually destroyed because of fighting during the Civil War but rather because of neglect. About a third of the population left the area for Texas and Louisiana to avoid the fighting during the war. Many never returned.

Arkansas seceded from the Union on May 6, 1861. This led to the closing of the Arkansas Military Institute in Tulip as the students were mustered for service to the Confederacy. The war had come in earnest to southern Arkansas by 1863, with a skirmish at Tulip in October and a skirmish at Princeton in December. Dallas County saw much activity in the following year’s Camden Expedition, a part of the larger Union action known as the Red River Campaign. The Camden Expedition was led by Union general Frederick Steele, whose army had previously captured the capital city of Little Rock. In the face of Confederate resistance in southwest Arkansas, Steele sought to return to Little Rock through Dallas County. Steele camped near Princeton, and his men foraged for supplies as the Confederates, under General Sterling Price, were still back in Camden working to complete a bridge across the Ouachita River to join the pursuit of Steele. Price was successful in catching Steele as his army attempted to cross the Saline River at Jenkins’ Ferry on April 29–30, 1864, resulting in the final battle of the expedition.

No fighting other than minor skirmishes leading up to the final battle at Jenkins’ Ferry actually occurred in Dallas County, including another skirmish at Princeton, but Confederate cavalry forces under General James Fagan were in a position to attack Steele there, camping only a few miles away north of Princeton. The Confederates did not attack, as they were apparently never aware of the Union presence and moved to resupply to the west without realizing the situation. Had they attacked, some historians speculate, Steele’s army could have been destroyed in Dallas County.

Even after the conclusion of hostilities, the war continued to impact life in the county. At least one lynching of a Unionist, James Kennedy, occurred after the war.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

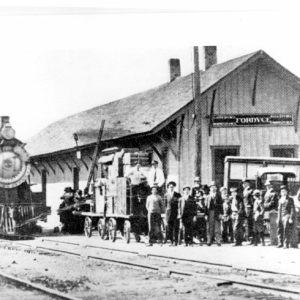

In 1881, the construction of four major railroads began in Dallas County. The first and most prominent was the Texas and St. Louis Railway, which was chartered in May by James W. Paramore to create a line to bring cotton from the fields in Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas to market in St. Louis, Missouri. During the summer of 1882, the Texas and St. Louis Railway was constructed across the southeast corner of Dallas County. Also in 1882, the city of Fordyce was platted to serve as a station on the railway.

The second major railway to pass through Dallas County was the Ultima Thule, Arkadelphia, and Mississippi Railway, organized in June 1883. It was intended to run as a logging line from Arkadelphia (Clark County) to Ultima Thule (Sevier County) but was never built farther west than Daleville (Clark County) and east to Dalark (Dallas County) and Sparkman (Dallas County).

On April 8, 1884, Fordyce was incorporated as a city. Two years after, in 1886, the Texas and St. Louis Railway switched from narrow to standard gauge and was renamed the St. Louis, Arkansas and Texas Railway (commonly known as the Cotton Belt).

By 1890, Fordyce already had the highest population of any town in Dallas County at 1,710. Princeton, still the county seat, consisted of only a half dozen stores, one hotel, and a few houses. In an attempt to reverse the town’s decline, on February 25, 1890, the Fordyce and Princeton Railroad Company was incorporated and began construction on a logging line from Princeton to Fordyce.

The timber industry continued to grow and, by 1900, was second only to agriculture as a source of income in the county.

Early Twentieth Century

The Little Rock and Southern Railway Company was incorporated to build a line through the eastern half of Dallas County from Haskell (Saline County) to El Dorado (Union County) in 1902. An African-American community, then known as Lea Ridge, was relocated farther west to provide another stop on the rail line and was renamed Carthage. The Rock Island Railway Company took ownership of the Little Rock and Southern Railway Company in 1905.

By 1908, Fordyce was the trade center of Dallas County and the center for railway connections in south-central Arkansas. This shift in economic importance to Fordyce also brought political clout, and the Dallas County seat was moved from Princeton to Fordyce. As a result, the construction of the Fordyce and Princeton Railroad turned from Princeton and toward Carthage, thus sealing the demise of Princeton as an economic and political influence.

In 1911, the Dallas County Courthouse was built in Fordyce. In the same year, the Malvern and Camden Railway Company was incorporated to build a line from Malvern (Hot Spring County) to Camden. The communities of Willow (Dallas County) and Manning (Dallas County) were developed to serve as stops on the line. The next year, the Ultima Thule, Arkadelphia, and Mississippi Railway shut down with the closing of a lumber company in nearby Clark County.

The town of Sparkman, having faded in previous decades, found rebirth northeast of its original location and was platted on the Malvern and Camden Railway line in 1913. Later in that year, the Malvern and Camden line became a part of the Rock Island. The “new” Sparkman survived and was incorporated in 1915.

During the 1920s, many county farms were sold to lumber companies. Farming, aside from the timber industry, is mostly confined to the southwest area of the county in the twenty-first century. The railroads began to lose their significance in the 1920s as the versatility of gas-powered vehicles changed the way logging was done, eliminating the need to build tracks and maintain infrastructure to support them for logging.

By 1930, Dallas County reached its peak population to date of 14,671. Gasoline-powered log trucks became more dependable, and their usage increased, not just in removing the timber but in all areas of transport within the industry. In 1940, the last trainload of logs pulled into the Fordyce station, signaling the end of an era.

World War II through the Modern Era

Dallas County lost around thirty soldiers during World War II out of approximately 600 who enlisted. Those who did not serve in the military had the opportunity to serve the war effort by working in nearby munitions plants in Calhoun and Ouachita counties.

Two members of the Rolling Stones were arrested passing through Fordyce in 1975, bringing international attention to the county.

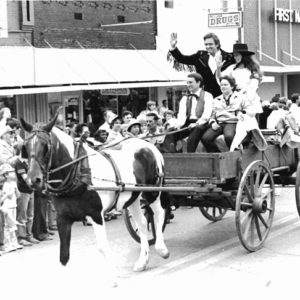

Reflecting the influence of railroads on the history of Dallas County, and particularly Fordyce, the first Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival was held in the city in 1981 and has been held annually in the city on the fourth Saturday in April ever since. Johnny Cash performed at the second annual festival in 1982.

The 2010 census of Dallas County showed a declining population of 8,116. The slowdown in the home-building industry in the early twenty-first century caused the price of timber to fall dramatically, prompting job losses in the timber industry, a source of income that the county is still vitally dependent upon. By 2020, the population had contracted to 6,482.

Another noteworthy source of income to the county is tourism, especially related to hunting. Estimations are that the influx of hunters doubles the economy during the height of deer season. Many former homesteads and lands are now host to well-established hunting clubs whose members purchase supplies in the nearby communities and have their kills processed locally.

Attractions in the county include the Dallas County Museum and multiple properties on the National Register of Historic Places. These include the Fordyce Commercial Historic District, the Dallas County Training School High School Building, and the Cotton Belt Railroad Depot, all in Fordyce. Other sites include the Ed Knight House near Pine Grove, the Butler-Matthews Homestead near Tulip, and the Captain Goodgame House at Holly Springs.

Famous Citizens

In 1863, famed African-American attorney Scipio Africanus Jones was born to a slave mother at a plantation near Tulip. College football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant lived with his grandfather in Fordyce when he was young.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Southern Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1890.

Dallas County Museum. Fordyce, Arkansas. http://www.dallascountymuseum.org (accessed February 14, 2022).

Huckaby, Elizabeth Paisley, and Ethel C. Simpson, eds. Tulip Evermore: Emma Butler and William Paisley, Their Lives in Letters 1857–1887. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1985.

Moneyhon, Carl, ed. “Life in Confederate Arkansas: the Diary of Virginia Davis Gray, 1863–1865—Part I.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Spring 1983): 47–85.

———. “Life in Confederate Arkansas: The Diary of Virginia Davis Gray, 1863–1865—Part II.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Summer 1983): 134–169.

Michael Hodge

North Little Rock, Arkansas

Revised, 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Arkansas Military Institute

Arkansas Military Institute Dallas County Museum

Dallas County Museum Kennedy, James (Lynching of)

Kennedy, James (Lynching of) Princeton, Skirmish at (April 28, 1864)

Princeton, Skirmish at (April 28, 1864) Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary

Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary "Bear" Bryant Exhibit

"Bear" Bryant Exhibit  Carthage Street Scene

Carthage Street Scene  Dallas County Courthouse

Dallas County Courthouse  Dallas County Courthouse

Dallas County Courthouse  Dallas County Map

Dallas County Map  George Dallas

George Dallas  Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Cake Train

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Cake Train  Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Parade

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Parade  Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival  Fordyce Train Depot

Fordyce Train Depot  Timber Cutting

Timber Cutting  Tulip Community Building

Tulip Community Building

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.