calsfoundation@cals.org

Jonesboro Lynching of 1881

aka: Greensboro Lynching of 1881

In March 1881, Martha (Mattie) Ishmael, the teenage daughter of planter Benjamin Russell Ishmael, was brutally murdered in the family’s home near Jonesboro (Craighead County). Four African Americans were accused of the murder and were bound over to the grand jury, but before they could be tried, they were lynched by a mob of masked men.

Benjamin Ishmael was born in Tennessee, but by the middle of the 1830s, he and his parents had settled in Arkansas in Greensboro (Craighead County), eleven miles east of Jonesboro. Greensboro, then located in Greene County, was settled around 1835, and was mostly occupied by small farmers. It was not until the late nineteenth century that the lush forests of the area would give rise to the timber industry. In 1838, Ishmael married Malinda McCracken in Greene County. She was a native of North Carolina and was quite young at the time of the marriage; different sources place her age between fourteen and seventeen.

The census indicates that, by 1850, the family, which was living in Big Creek Township in Greene County, included six children. Mattie Ishmael was apparently the tenth child in this family, born around 1863. Around that time, her brother Benjamin, by then married and a father, was killed in a skirmish near the mouth of Richland Creek in Searcy County while serving in the Second Arkansas Cavalry (US).

Although the Black population was small in Craighead County, the county—like many in Arkansas—faced racial unrest during Reconstruction. There was considerable Ku Klux Klan activity in the area, much of it centered around Greensboro. In 1868, Governor Powell Clayton placed the county under martial law and sent militia to stop the Klan activity in the area.

In 1868, Malinda Ishmael died. Benjamin Ishmael was living in Powell Township with his son Henry and his daughter Mattie by 1870. He and Mattie were still living there in 1880, Henry having married and established his own home. By this time, there were only 261 African Americans in the entire county, accounting for a scant 3.7 percent of the population.

According to newspaper accounts, at some time during the first week of March 1881, Benjamin Ishmael left Mattie at home while he made a quick trip to the nearby mill. According to the Omaha Daily Bee, when he returned home several hours later, “he found his daughter lying on the floor of the sitting-room, weltering in a pool of blood.” It appeared that she had been beaten with an ax or a club, and the room showed signs of a struggle. Mattie was unconscious when her father found her and died before she could reveal any details about her attackers. Her attackers were allegedly in search of money that her father had hidden in the house. According to the Bee, “The neighborhood of the tragedy is in a fever of excitement, and the sequel may be the appearance of, and some swift work by, Judge Lynch.”

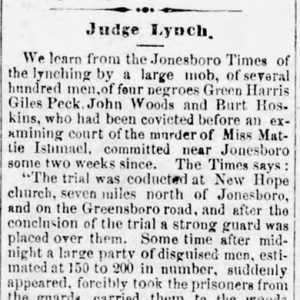

On March 12, the Decatur Daily Republican reported that four Black men—Green Harris (sometimes referred to as Hawes), Giles Peck, John Woods (sometimes referred to as Jud Woods), and Burt Hoskins (sometimes referred to as Haskins)—had been arrested and tried before magistrates Jackson and Akers at New Haven Church, eight miles north of Jonesboro. The hearing, which found that the men were guilty, was attended by several hundred people. According to this and several other reports, the accused made a complete confession. The magistrates bound them over to the grand jury, and they were ordered taken to the jail in Jonesboro. The hour being late, however, it was decided to hold them overnight in the church under a strong guard. The large crowd gradually dispersed, “muttering threats of vengeance.”

Around midnight, between 200 and 300 masked men surrounded the church, overpowered the guards, and broke in the doors and windows. They seized the accused, dragged them to a tree about 200 hundred yards away, and hanged them. Once again, the crowd dispersed, “leaving the bodies of their victims dangling in the air and presenting a horrible spectacle in the moonlight.” According to the Republican, “The crime and punishment form one of the blackest pages in the annals of the state.”

Few details are known about the four men who were lynched. Only one, Green Harris, was listed in Craighead County at the time of the 1880 census. He was a twenty-year-old farmer, a native of Mississippi, living in Powell Township with his wife, Jane. There was a Burt (Birt) Hoskins in Poinsett County, Arkansas, in 1880. He was a twenty-six-year-old single barber, living in the household of Aggie Harris. Living in the same home was a twenty-nine-year-old laborer named Jarvis Peck.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Lynching.” Daily Globe (St. Paul, Minnesota), March 12, 1881, p. 1.

“Terrible Fate of a Young Lady.” Omaha Daily Bee, March 11, 1881, p. 1.

Untitled article. Decatur Daily Republican (Decatur, Illinois), March 12, 1881, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

My great-grandfather, Hiram Wyatt Ishmael, was a first cousin to Mattie Ishmael (their fathers were brothers), and Hiram was close to the same age as Mattie. He was present at the hanging and told the family that for the rest of his life, he had nightmares about what he saw that fateful evening. He told about riding along in his buckboard one night when he imagined that he felt the hands of those men hanged on his body. My grandmother, Lola Ishmael Graddy, who lived with us for much of her long life of 85 years, told me stories about the murder, and she would always look under her bed at night before she went to sleep. She was told that the one who murdered Mattie was hiding under Mattie’s bed and attacked her when she came into the room.