calsfoundation@cals.org

Greene County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Paragould |

| Established: | November 5, 1833 |

| Parent county: | Lawrence |

| Population: | 45,736 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 577.34 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

| 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 |

| – | – | – | 1,586 | 2,593 | 5,843 | 7,573 | 7,480 | 12,908 | 16,979 |

| 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 |

| 23,852 | 26,105 | 26,127 | 30,204 | 29,149 | 25,198 | 24,765 | 30,744 | 31,804 | 37,331 |

| 2010 | 2020 | ||||||||

| 42,090 | 45,736 | ||||||||

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

41,038 |

89.7% |

| African American |

933 |

2.0% |

| American Indian |

163 |

0.4% |

| Asian |

181 |

0.4% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

292 |

0.6% |

| Some Other Race |

699 |

1.5% |

| Two or More Races |

2,430 |

5.3% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

1,596 |

3.5% |

| Population Density |

79.2 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$47,056 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$23,494 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

16.4% |

|

For many years, Greene County’s main attraction, Crowley’s Ridge, was isolated because of swamplands on three sides: the St. Francis River bottoms to the north and east, and the Cache and Black River lowlands on the west. But drainage of the swampland led to growth in the area, and, in starting in the mid-twentieth century, many industries set up shop in the county. Its county seat of Paragould has been labeled as the safest city in Arkansas by the Arkansas Crime and Information Center.

Pre-European Exploration

Beginning about 18,000 years ago, the melt water from the Laurentide glacier that covered much of North America created a sluiceway that “washed out” much of the soft sedimentary soil of the old Gulf of Mexico in the middle-south area of what is now the United States. About 16,000 years ago, the wide flow declined to a point, leaving two great rivers with a long ridge of land between them. The faster- and heavier-flowing Mississippi River eventually cut through the ridge south of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, and joined the Ohio River at Cairo, Illinois. Crowley’s Ridge, as it was later called, was greatly influential in the shaping of Greene County. The first Native Americans arrived in the area more than 10,500 years ago. In 1974, Dan Morse and colleagues with the Arkansas Archeological Survey uncovered in southwest Greene County the earliest recognized cemetery in the New World. The find indicated a territorial stability of people previously believed to be too nomadic to have designated a specific site for burials. Other archaeological finds in the county reveal that the Indians have occupied the ridge area through a long history of changing cultural traditions.

European Exploration and Settlement

Louisiana Governor Antoine de La Mothe Cadillac was probably the first European to visit this part of northeast Arkansas. In 1715, the French crown ordered him to explore the headwaters of the St. Francis River. Indians with whom he came into contact reported that the area contained silver, though he found only lead near Fredericktown, Missouri. Suffering great discomfort while ascending the river, he wrote in his diary: “This colony is a monster…. I have never seen anything so worthless.” However he felt about the area, he did move European civilization closer to what is now Greene County.

Records in the old Powhatan Courthouse reveal that Pierre LeMieux was the first European to settle in the area. In the early 1790s, he developed a place he called “petite baril,” later translated to Peach Orchard. He died in 1817.

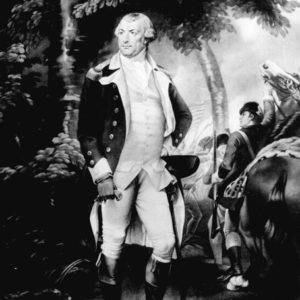

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In 1815, Benjamin Crowley moved his family from Kentucky to Lawrence County in Arkansas. He settled on the Spring River and farmed in an area regional historians called “the second Garden of Eden.” In December 1821, Crowley crossed the Black and Cache rivers to explore the ridge area. Armed with a War of 1812 land grant, “Old Ben” selected a vacated Delaware Indian site that had developed around a large spring on a ridge. No one knows when the ridge became known as Crowley. Some pioneers had settled on the lower ridge area near Helena (Phillips County) several years before Crowley’s home became the community meeting place where county officers discussed and solved civic matters. When the volume of legal and court activities required a seat of law, Isaac Brookfield and Lawrence Thompson wrote a petition seeking permission to organize a county. The territorial legislature approved the petition in November 1833. Three local historians report that the county seat remained in Crowley’s home until it was moved to a town called Paris, but no document or town site has been found to prove Paris even existed. The county is named for Revolutionary War general Nathaniel Greene.

In 1840, the county voted to move the seat of government to Gainesville, so named because “it gained the county seat.” Two documents were found in 1996 indicating that Gainesville was laid out with eighty-six lots, and a state tax auditor’s report dated May 18, 1842, noted that “nearly all lots were sold and deeded to the purchasers.”

The lowlands of the St. Francis, Cache and Black rivers slowed settlement in Greene County. In 1849, Congress passed an act intended to reclaim the swamplands. It transferred all the Arkansas swamplands to the state and provided funds for locating, evaluating, and draining.

With a new county seat on an improved road running to Helena, the growth of Gainesville, the drainage activities, and the arrival of land speculators, Greene County finally began to boom in the mid-1850s. But the area south of Greene County was booming as well. In 1859, the state legislature passed an act taking parts of Greene, Mississippi and Poinsett counties to create Craighead County. Greene County lost six square miles of its south border.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The Civil War interrupted the county’s economic growth. James W. Bush was selected to attend the Arkansas Secession Convention. He voted twice against secession, but during the May 6, 1861, session of the convention, an ordinance to secede passed 69-1, with Bush following the majority. A Home Guard unit, one cavalry, and four infantry companies were formed, mostly from Greene County. All saw considerable action fighting with the Army of Tennessee. Casualties were high. Another cavalry company was formed to join General Sterling Price’s raid into Missouri in the fall of 1864. It was assigned to Lieutenant Colonel Davies Battalion, Joseph O. Shelby’s division, and also suffered heavily.

During the war, “Nate” Bolin, a native of Cape Girardeau, organized a guerrilla unit. He was joined by notorious bushwhacker Sam Hildebrand. Operating out of Scatterville, near Rector (now in Clay County), Bolin and Hildebrand’s brigands frequently raided Union units in southeastern Missouri. The Scatterville camp was destroyed in 1864, but Bolin and Hildebrand continued to operate with a smaller band until May 1865, when General Jeff Thompson of the Missouri State Guard surrendered his command.

Postwar recovery was slow. County offices were filled by Unionist officials, but the control was not harsh. However, Governor Powell Clayton declared martial law in Greene County in 1868 because of reports that African Americans were being mistreated at a Walcott mill. When Clayton’s militia moved up the Greensboro Road toward Walcott, the unit was met by the Greene County “Home Guards” (Ku Klux Klan) commanded by Benjamin H. Crowley, “Old Ben’s” grandson. They fought a skirmish around Wiley’s Mill at Bucksnort, just south of the Greene County line. After several were wounded and one home guard was killed, the militia retreated to Jonesboro (Craighead County). Martial law was lifted several weeks later.

Reconstruction ended in the county in 1873. After newly elected State Representative B. H. Crowley negotiated a deal with the liberal Republicans, a new election was held in the county, and ex-Confederates were elected to all county offices.

In November 1872, Cairo-Fulton Railroad construction crossed the Missouri border into Randolph County. Greene County officials helplessly watched the economic boom to the west. By 1874, the rail line had become part of the St. Louis Iron Mountain (Missouri Pacific) system. It operated across the full length of Arkansas. During the 1873 spring legislative session, Crowley introduced a bill to create Clayton County from the northern part of Greene County. Because they did not like Governor Clayton, the citizens of the new county voted in 1875 to change the county name to Clay. Greene County then gained a small part of Randolph County, but ten years later gave up a small northeast area to Clay.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

Jay Gould gained control of the Iron Mountain in 1880. He learned that James Paramore’s St. Louis-Texas Railroad (Cotton Belt) was licensed to build a cheaper narrow gauge line through Arkansas to Texas. Gould decided to construct a regular gauge line to closely parallel Paramore’s route. It would branch off the main Iron Mountain line at Knobel (Clay County) and run through Greene County toward Helena. The railroads crossed six miles south of Gainesville. After “The Crossing” gained a post office, the postmaster named the town Paragould, deriving the name from Paramore and Gould. The new town grew rapidly and became the county seat in 1884, beginning the sharp and sudden decline of Gainesville. Other towns in Greene County associated with the railroad include Marmaduke, Delaphine, and Bertig.

Northeastern Arkansas offered one of the few remaining hardwood forests in the nation. With rail transportation and drainage improvements, Greene County experienced a major boom. Industry involving timber and timber-related products grew rapidly. At the time, more tight-barrel staves were shipped out of Greene County than any other place in the world.

A number of racially based incidences of violence took place in the county in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These events cumulatively led the already small African American population of the county and particularly Paragould to decrease steeply.

Early Twentieth Century

The drained and newly cleared bottomland on both sides of Crowley’s Ridge led to the development of large farm operations before the turn of the century. Timber-related businesses continued to spur industrial growth through the 1920s, but as the timber business declined, production of cotton, corn, and soybeans increased. Significant rice production did not come to the county until after World War II.

The railroads continued to dominate industrial activities. The Missouri Pacific located one of its large “roundhouse” machine shops in Greene County in 1911, and the shops serviced large steam locomotives well into the 1950s. At one time, the Missouri Pacific rail yard and “roundhouse” employed about 300 people.

The Paragould War Memorial, dedicated in 1924, is a Statue of Liberty replica honoring the men from the county who fought and died in World War I.

The economy of Greene County surged during the 1920s, but the stock market crash of 1929 and the drop in cotton prices bankrupted many area families. The federal government, in response to the Depression, established the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to provide work for unemployed young men. Led by Belle Wall, the Chamber of Commerce director, the county applied for assistance through the Arkansas Department of Parks. The CCC moved onto the old Crowley plantation site, constructed barracks, and built an attractive pavilion, an amphitheater overlooking a spring-fed lake, and many camp sites on the 270 acres that Crowley had settled in 1822. More than 10,000 people attended the opening of Crowley’s Ridge State Park in 1933, the 100th anniversary of Greene County.

The Paragould Meteorite struck in the southern part of the county in 1930. At the time, it was the largest recovered meteorite in the world.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Greene County native Paul Page Douglas became a highly decorated fighter ace during World War II. Seventy-eight Greene County military men lost their lives during World War II, and Greene County, like other agricultural-based communities, suffered significant population loss during the three decades following the war. The Ely Shirt Factory was the only large plant in Greene County. By 1950, county officials began an effort to attract larger plants.

The first big plant with international connections, Emerson Electric of St. Louis, Missouri, came to Paragould in 1955. Manufacturing small electric motors for home appliances, Emerson first employed about 500 people. Though production has fluctuated, the Paragould plant produced more fractional horsepower electric motors in some years than any other plant in the United States and at times employed near 1,300 workers.

Modern Era

A 2001 census study revealed that the non-farm paid employment force in Greene County was greater than one-third of the total paid workforce. This figure, 33.4 percent, was below the state average of 37.2 percent. After that, however, several major manufacturing facilities (including two large railcar plants) located in the county.

Chamber of Commerce studies have shown that industry and commerce in the county are served by thirteen motor freight carriers, two main-line railroads, four major highways, and a charter-service airport. County facilities include an improved Crowley’s Ridge State Park, Lake Frierson State Park, several well-equipped playground facilities, Crowley’s Ridge College, two vocational-technical schools, an Arkansas State University satellite facility, an award-winning daily newspaper, two fully accredited public school systems, a county museum, a new courthouse with modern facilities, a new county jail, and a restored courthouse.

Famous residents of Greene County include actress Lee Purcell, artist Edward Everett Burr, criminal Frank Nash, and politician Jimmie Lou Fisher.

For additional information:

Crowley, B. H. History of Greene County. Paragould, AR: B. H. Crowley, 1906.

Greene County, Arkansas: History and Families. Vol. 1. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 2001.

Greene County, Arkansas: History and Families. Vol. 2. Nashville, TN: Turner Publishing Company, 2009.

Greene County Historical and Genealogical Quarterly. Paragould, AR: Greene County Historical and Genealogical Society (1988–).

Greene County Historical Quarterly. Paragould, AR: Greene County Historical Society (1964–1986).

Hansbrough, Vivian. History of Greene County, Arkansas. Little Rock: Democrat Printing and Lithographing Co., 1946.

Muller, Myrl. A History of Greene County, Arkansas. Little Rock: Parkhurst Book Design, 1984.

Mack Hamblen

Greene County Historical Society

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Arkansas Department of Workforce Services (ADWS)

Arkansas Department of Workforce Services (ADWS)  Corner Cafe

Corner Cafe  Crowley's Ridge

Crowley's Ridge  Crowley's Ridge State Park

Crowley's Ridge State Park  Crowley's Ridge State Park

Crowley's Ridge State Park  Delaplaine Street Scene

Delaplaine Street Scene  Gainesville Street Scene

Gainesville Street Scene  Greene County Museum

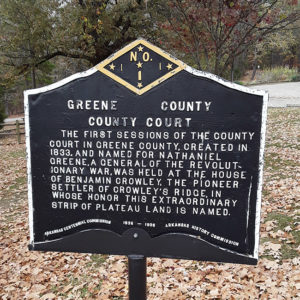

Greene County Museum  Greene County Court Plaque

Greene County Court Plaque  Greene County Courthouse (1888)

Greene County Courthouse (1888)  Greene County Courthouse (1888)

Greene County Courthouse (1888)  Greene County Map

Greene County Map  Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene  Lake Frierson State Park

Lake Frierson State Park  Light

Light  "Mama's Opry," Performed by Iris DeMent

"Mama's Opry," Performed by Iris DeMent  Marmaduke Street Scene

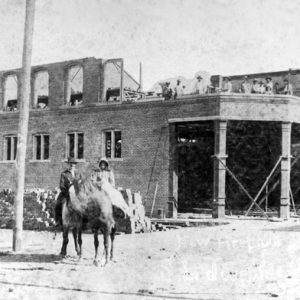

Marmaduke Street Scene  Paragould Building Construction

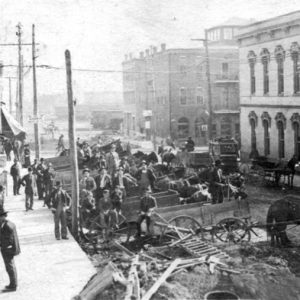

Paragould Building Construction  Paragould Street Scene

Paragould Street Scene  Security Bank

Security Bank

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.