calsfoundation@cals.org

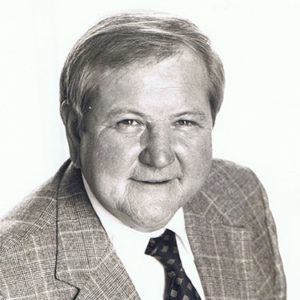

John Thompson (Jack) Meriwether (1933–2013)

John Thompson (Jack) Meriwether was a city administrator whose later career in higher education channeled hundreds of millions of dollars to Arkansas colleges and universities. Meriwether was city manager—the city’s chief administrator—of Texarkana (Miller County) and then Little Rock (Pulaski County). He was an officer at a bank in his hometown of Paragould (Greene County) and was general manager of the Arkansas Gazette for several years. He also served as vice president for governmental relations for the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County).

Jack Meriwether was born on November 23, 1933, to Ray Meriwether and Marie Thompson Meriwether in Paragould. His father and his uncle, Bill Meriwether, ran a hardware store started by his grandfather in 1883. Meriwether and his cousin, Robert W. Meriwether, spurned careers in the family business and sold it. Meriwether attended The Citadel in Charleston, South Carolina, for two years and then received a bachelor’s degree in political science and economics at UA.

After graduation, he became an intern in the city manager’s office in Little Rock, which triggered an interest in public service and administration. He enrolled at the University of Kansas in Lawrence and received a master’s degree in public administration. He was a U.S. Army infantry officer in Korea after hostilities ended there.

The City of Little Rock hired him as an aide to the city manager in 1959, and he was soon promoted to assistant city manager. Texarkana hired him as city manager in 1964. At the time, the city was beset by social and economic decline, high crime, and racial and labor conflicts. Meriwether persuaded the city to approve an industrial bond issue that attracted Cooper Tire and Rubber Co. to Texarkana; the company became the largest employer in area. During his tenure, Texarkana was designated as a Model City in President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty, which attracted tens of millions of dollars of federal aid for improvements in blighted neighborhoods. It also brought an influx of workers under the federal VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) program. The racially integrated force of VISTA workers organized poor neighborhoods to work for improvements, which created some conflict in the rigidly segregated city.

Little Rock’s city board of directors faced labor strife in 1969. The city’s garbage workers, recently organized by a government workers union, went on strike, and the city manager left town when policemen called in sick, which was referred to as “blue flu,” to protest the city’s lack of concern about their pay and working conditions. The board fired the city manager and hired Meriwether, a champion of unions.

The city entered a long period of harmony with its organized work force, with Meriwether handling negotiations with the union and the police and firemen’s fraternal orders. When the city undertook the development of University Avenue and the widening of state Highway 5 from downtown to the city’s western border, Meriwether—who was then the assistant city manager—did much of the negotiation over easements with business owners, which cost the strapped city very little. Later, when a developer submitted plans for a subdivision west of University Avenue, Meriwether told him that the city would view it more favorably if it had a wooded park and playground in its center. The city later would name it Meriwether Park.

Drawing on his experience at Texarkana, Meriwether had Little Rock included in the second round of Model Cities. Downtown renewal included a convention hotel built atop a municipal parking garage and connected to the city’s old municipal auditorium. A program called “New Careers” gave on-the-job training to young African American men and women to prepare them for professional jobs in the all-white ranks of city government. Several African Americans with training in the program—including Mahlon A. Martin, Bob Nash, and Nathaniel Hill—went on to distinguished careers in state and national government and with foundations. Martin, who got his start under Meriwether, became Arkansas’s first black city manager and the state government’s first black chief administrator as director of the state Department of Finance and Administration.

Meriwether’s creed was that public administrators should move after five years because they will have reached the end of their effectiveness and accumulated too many enemies. Concluding his five years as city manager of Little Rock (he had spent about five years in the same position in Texarkana), Meriwether resigned in 1974 and went back to Paragould as vice president for development at the First National Bank of Commerce.

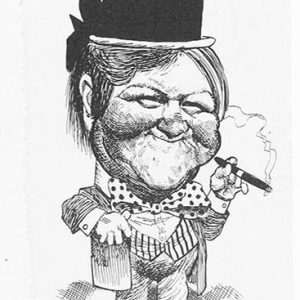

Under the caption “The House that Jack Built,” the Arkansas Democrat published a cartoon by its editorial cartoonist, Jon Kennedy, showing Meriwether having just finished building a house labeled “New Era of Little Rock Progress.” A year later, he returned to Little Rock, partly so that his wife, Peggy Crane Meriwether of Fort Smith (Sebastian County), who was suffering from cancer, could be near medical facilities. His wife died in 1983; both of the couple’s sons died as young men.

Meriwether began his seven years as general manager of the Arkansas Gazette in 1975, hoping to save the newspaper, which was engaged in a competitive war with the Arkansas Democrat. Meriwether chaired a task force appointed by Governor Dale Bumpers, which in 1975 recommended sweeping reforms in public and higher education, and he was chairman of the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, which was set up by the former governor to invest in education and economic development to improve the status of minorities and the poor in Arkansas.

Hoping to use Meriwether’s interpersonal skills and goodwill to improve the University of Arkansas’s standing with state government, UA president James E. Martin hired him as vice president for university relations in 1982. At the special session of the legislature in 1983 to address education needs, Meriwether lobbied to get Governor Bill Clinton’s sales tax passed, but then he lobbied legislators to earmark $50 million of the annual proceeds for higher education. Clinton and his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, had promised that all of the tax would go into a special fund that would forever serve only the public schools. The legislature adopted Meriwether’s plan, however, enraging the Clintons.

When Ray H. Thornton Jr. became president of the university a few months later, the Clintons persuaded him to direct Meriwether not to lobby the legislature again. Meriwether turned his attention to the federal government, first obtaining a Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation grant to study ways in which government aid might improve the research and development capabilities of the state’s universities. His old friend Senator Bumpers by then was a member of the Senate Appropriations Committee. Over the next dozen years, Bumpers steered some $120 million in grants to UA and its campuses, many of them for agricultural, engineering, and medical research.

In 2008, Meriwether married Judy Thompson, a longtime friend.

Meriwether died on June 27, 2013. His ashes were scattered in Paragould.

For additional information:

Marmaduke, Jacy. “Witty, Determined, Transformed Cities.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 28, 2013, p. 6B.

Obituary of John T. “Jack” Meriwether. Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 28, 2013, pp. 7B.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Jack Meriwether Cartoon

Jack Meriwether Cartoon  Jack Meriwether

Jack Meriwether  Jack Meriwether Caricature by George Fisher

Jack Meriwether Caricature by George Fisher

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.