calsfoundation@cals.org

Homer

The Homer was a steamboat that plied the waters of the Ouachita River in the early 1860s. It achieved significance for its role in the Camden Expedition of 1864, when Union troops seized it, along with its cargo, and sunk it. Confederate soldiers later used its timbers to bridge the Ouachita.

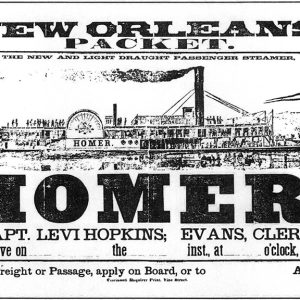

The Homer, built for $30,000 in Parkersburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), in 1859, went into service on November 14, 1859, at the Port of Cincinnati, Ohio. It was a 194-ton sidewheel packet measuring 148 feet long, twenty-eight feet wide, and five feet deep. Its co-owners were Levi Hopkins of Mason County, Virginia, and his father-in-law, stock dealer and farmer William H. Neale of Parkersburg.

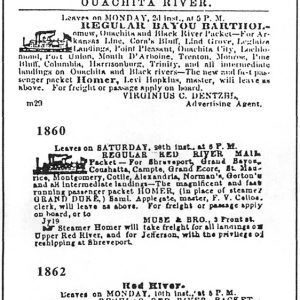

Neale and Hopkins sold the Homer in the spring of 1860 to Samuel Applegate and James Parsons soon after it was enrolled at the Port of New Orleans, Louisiana, where Applegate, who served as the ship’s master, ran it on the Red and Ouachita rivers as a regular mail packet. Ambrose W. Skardan bought out Applegate’s two-thirds interest in the vessel in 1861.

After the Civil War began, the Homer was placed under contract to the Confederate government, transporting men and supplies on the Mississippi, Red, and Ouachita rivers. Its role was not an uncommon one after Union troops captured New Orleans, as commercial trade became both rare and risky as Federal forces pressed westward.

The Homer continued carrying personnel and materials up the Mississippi to the Rebel defenders of Port Hudson, Louisiana, and various places on the Red and Ouachita rivers throughout 1863 and early 1864. It was far up the Ouachita, about thirty miles below Camden (Ouachita County), when it was captured by troops of Major General Frederick Steele’s Union army during the 1864 Camden Expedition.

Steele led an army of around 6,800 Union soldiers out of Little Rock (Pulaski County) on March 23, 1864, to link up with Major General Nathaniel Banks on the Red River for a combined drive into Texas. Steele was reluctant to participate, in light of the poor roads of southern Arkansas and the fact that the area through which his army would march was known to be virtually picked clean of foodstuffs, with what was left likely to be taken or destroyed by Confederate cavalrymen who roamed the area.

Steele’s army skirmished with Confederate troops during the march south and skirmished heavily at Elkin’s Ferry and Prairie D’Ane. Fearing that rumors of Banks’s defeat in Louisiana were true, they abandoned the drive toward the Red River and turned instead to Camden. The Union army, now swelled by the arrival of an additional Federal column from Fort Smith (Sebastian County), faced a real prospect of starvation. Captain Charles A. Henry, the Union quartermaster, reported that when Steele’s troops reached Camden on April 15, “there were about 800 wagons and nearly 12,000 public animals….The difficulty of procuring forage occasioned great uneasiness, as we were without any base of supplies and with an active enemy in front….Our supplies of breadstuffs were entirely exhausted, and it was thought best to try and procure sufficient corn to furnish half allowance of forage and one-fourth rations of meal to the men.”

The Homer’s fate became entwined at this time with that of Steele’s army, though it was far enough up the Ouachita to be safe from Union warships. A detachment of the First Iowa Cavalry and Third Missouri Cavalry (US) captured the Homer around thirty miles below Camden. The vessel was “laden with corn and other quartermaster and commissary supplies. Lieutenant J. T. Foster of Company B, First Iowa, an old Mississippi River steamboat pilot, took the wheel and piloted the boat back to Camden.”

The Homer held between 3,000 and 5,000 bushels of corn, which were swiftly consumed by the hungry Union troops. Steele sent foraging expeditions into the country around Camden, but Confederate cavalry ambushed a foraging column at Poison Spring on April 18 and defeated another column bringing food from Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) at Marks’ Mills on April 25. Steele decided to retreat to Little Rock before his army was destroyed.

Steele’s army began to march, crossing the Ouachita River on the night of April 26 after destroying ninety-two wagons and a large amount of harness equipment that had to be abandoned because the starving Union horses and mules were incapable of pulling them. The Homer apparently was sunk at this time by Union troops to prevent it from returning to Confederate service. Steele’s army quietly removed its pontoon bridge and headed toward Little Rock, leaving the Confederates on the opposite side of the Ouachita with no means of crossing.

The Confederates turned to the Homer to solve the problem. The steamer’s cabin remained above water, and the Rebels salvaged 10′ x 12′ planks. The planks were hammered into crude rafts that were strung together across the Ouachita. It was not until the morning of April 28 that the bridge was declared open to traffic, allowing the Confederate army to resume its pursuit of Steele’s troops. After a savage battle at Jenkins’ Ferry on April 30, Steele succeeded in extricating his army across the swollen Saline River and completing his retreat to Little Rock.

The Homer shipwreck site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 14, 2002. As an archaeological site, the Homer shipwreck preserves important information, both within the vessel itself and the historical record it contains.

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin C. Steele’s Retreat from Camden and the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry. Little Rock: Eagle Press of Little Rock, 1990.

Drexler, Carl G. “The S.S. Homer Rises from the Ouachita.” Arkansas Archeological Survey. https://web.saumag.edu/aas/2021/12/13/the-s-s-homer-rises-from-the-ouachita/ (accessed December 14, 2021).

Edwards, John Newman. Shelby and his Men: or, The War in the West. Waverly, MO: General Joseph Shelby Memorial Fund, 1993.

“The Homer (Shipwreck).” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Lothrop, Charles H. A History of the First Iowa Cavalry Veteran Volunteers, from its Organization in 1861 to its Muster out of the United States Service in 1866: Also, a complete Roster of the Regiment. Lyons, IA: Beers & Eaton, 1890.

Pearson, Charles E., and Allen R. Saltus Jr. Underwater Archeology on the Ouachita River, Arkansas: The Search for the Chieftain, Haydee and Homer. Baton Rouge, LA: Coastal Environments, Inc., 1992.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. 34, part 1. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1891.

Mark K. Christ

Arkansas Civil War Sesquicentennial Commission

Historic Preservation

Historic Preservation Military

Military Homer Ad

Homer Ad  Homer Shipwreck Site

Homer Shipwreck Site  Homer Steamboat Schedule

Homer Steamboat Schedule

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.