calsfoundation@cals.org

Johnson County

| Region: | Northwest |

| County Seat: | Clarksville |

| Established: | November 16, 1833 |

| Parent County: | Pope |

| Population: | 25,749 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 661.00 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

3,433 |

5,227 |

7,612 |

9,152 |

11,565 |

16,758 |

17,448 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

19,698 |

21,062 |

19,289 |

18,795 |

16,138 |

12,421 |

13,630 |

17,423 |

18,221 |

22,781 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25,540 |

25,749 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

20,088 |

78.0% |

| African American |

482 |

1.9% |

| American Indian |

274 |

1.1% |

| Asian |

926 |

3.6% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

36 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

1,952 |

7.6% |

| Two or More Races |

1,991 |

7.7% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

3,439 |

13.4% |

| Population Density |

39.0 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$38,511 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$21,010 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

22.7% |

|

Johnson County has been the location of much of the state’s coal mining as well as one of the centers of the state’s peach industry. The northern section of Johnson County is located within the Boston Mountains, which consists of the entire southern boundary of the Arkansas Ozarks, and within the boundaries of the Ozark National Forest. It is characterized by mountains, thickly forested landscape, and streams and rivers. The southern region of the county is located in the Arkansas River Valley and consists of lowland bottom lands. Johnson County has five creeks/rivers: Horsehead, Little Piney, Mulberry, Spadra, and Big Piney. The county is also home to the University of the Ozarks.

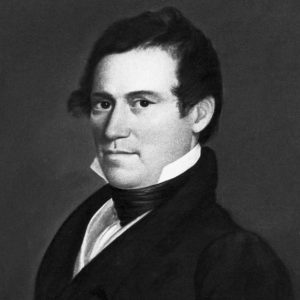

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Native American rock art, such as the King’s Canyon Petroglyph Site (which is on the National Register of Historic Places), as well as over 600 recorded campsites, indicate that people lived in this area for at least 10,000 years. At the time of the Louisiana Purchase, the Osage laid claim to the land, though they gave up such claims in an 1808 treaty with the United States government. Present-day Johnson County was part of a Cherokee reservation established between 1818 and 1828, and there an Indian factory on Spadra Creek to serve the Cherokee. Matthew Lyon served as the U.S. factor to the Cherokee Nation around 1820. Early white settlers started arriving in the first three decades of the eighteenth century, first by keel boat and later by steamboat; many were likely illegal squatters, who were a constant source of annoyance and complaint to the Cherokee. The county was created from Pope County and named after territorial judge Benjamin Johnson in 1833. The first county seat was Spadra, located on the Arkansas River. In 1837, the county seat was moved to Clarksville.

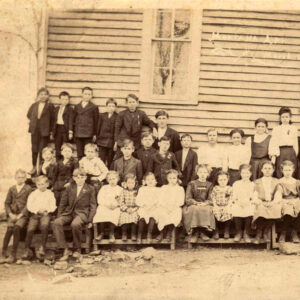

The earliest schools were pay schools, which were held in private homes and employed hired tutors. In 1843, a public school system law was passed but did not require a school-supported tax; only in 1866 was it made legal for taxation to support the educational system. By 1860, there were at least forty-nine schools in the county. Other schools that originated in the county included the Female Seminary School, the Deaf Mute Institute, and the School for the Blind.

Johnson County has a history of slavery, which began from the time of the earliest white settlers and lasted through the Civil War. Slavery was practiced in both the upland and low bottomlands of the county. However, the slave population in Johnson County was small compared to other parts of the state: In 1860, there were only 7,612 persons in the county (6,639 whites and 973 African Americans).

Civil War through Reconstruction

The impact of the Civil War hit Johnson County in the first year of the war. Even though no Civil War battle occurred in the county, violence, contested ground, destruction, and general disturbance occurred. Many areas were occupied by Union soldiers (such as the Union forces occupying Clarksville), who burned several buildings in the area to prevent their use by Confederates. The county courthouse experienced damage from both sides of the conflict. Like in other parts of the Ozarks, many people participated in guerrilla warfare. The rural regions and towns experienced robberies, property theft and destruction, murder, and other forms of violence. At least three engagements took place in the county: the Skirmish at Buffalo Mountains, the Skirmishes at Clarksville, and the Affair at Clarksville.

Reconstruction in Johnson County consisted of continual violence and political difficulties. One of the most famous violent episodes was the 1873 murder of Judge Elisha Mears. The man suspected in the killing was “noted desperado” Sid Wallace, who attempted to assassinate a Joseph T. Dickey, a St. Louis drummer (or a railroad foreman, depending upon the source), in the spring of 1872 and who was convicted of murdering Constable R. W. Ward of Clarksville. A widespread account of Wallace tells that he witnessed his father’s murder by Union soldiers (or by local bushwhackers disguised as Union soldiers) when he was twelve and, after his twenty-first birthday, traveled widely to eliminate the men responsible, men who had remained in the area as “carpetbaggers.” However, Wallace committed other murders as well, perhaps as part of a gang of outlaws, before he was arrested. Wallace managed to take control of the Clarksville jail on November 25, 1873, and shot at citizens from the jail window, killing Thomas Paine, who had testified against him in the murder trial. He was finally hanged on March 14, 1874, an event that drew observers from across the county.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The emergence and use of the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad, which was completed from Little Rock to near Clarksville in 1872 and on to Fort Smith (Sebastian County) in 1874, as well as telegraph lines, connected Clarksville and other towns to the rest of the nation. Likewise, the coal mining industry increased in size and provided jobs for many citizens in the county. Coal had first been found in 1840 on an outcropping on Spadra Creek, and barges began shipping coal to Little Rock and other places in 1843, though it was not until the advent of railroads in the county that the industry became profitable. The principal population centers connected with coal mining were Coal Hill, Spadra, Jamestown, Hartman, Montana, and Clarksville. Fletcher Sryglay, the land agent for the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad, recruited many European immigrants for the coal mines, adding to the cultural diversity of the area, especially in the emergence of Catholic and Lutheran populations. However, the use of Slavic immigrants to break a strike led to what is called the Jamestown War, in which many men died. Another notable strike took place in 1915.

An African-American man named Hemp Neal was lynched on November 5, 1878, outside of Clarksville for allegedly raping a young white woman. This was the first recorded lynching in Johnson County. Three years later, Charles Jones was executed after a short trial when he was accused of attacking a white woman.

Coal Hill, settled in 1876 and originally known as Whalen’s Switch, was a violent and dangerous place in the later part of the century, reporting numerous incidents of drunken fights, murders, and robberies. However, in 1887 and 1888, Coal Hill shipped ten times as much coal as the rest of the state and, between 1910 and 1920, was the second-largest town in the county. This success was in part due to the employment of the convict lease system, in which prisoners served as veritable slave labor. An early strike in 1886 made public the horrors of the system in which convict miners were kept in filthy quarters and whipped if they did not meet their daily quotas. An 1888 legislative inquiry resulted in a few minor changes to the system, though convicts continued to be used for mining coal for many years to come.

Also during this period, the timber industry took hold in Johnson County and surrounding counties, following the railroad into the region. The closest lumber mill was in Cass, which is located in the northeast section of Franklin County. Throughout all of the Arkansas River Valley, Johnson County has the largest amount of timber. In 1891, at least ten different types of trees were harvested for timber. However, the timber industry provided only a temporary respite of prosperity, eventually declining in the 1930s and leaving many people to seek better opportunities elsewhere. In some cases, towns disappeared because they functioned based on the prosperity and success of the lumber industry. Starting in the 1930s, the U.S. Forest Service began buying up land that had been cleared and repopulating it in hopes of returning what was lumbered away.

The Brothers of Freedom organized in Johnson County in 1882 to support agricultural workers. It eventually merged with the Agricultural Wheel.

Arkansas Cumberland College opened its doors in Clarksville on September 7, 1891, following the closure of Cane Hill College, which had left Cumberland Presbyterians without an educational institution of their own in the state. It later changed its name to the College of the Ozarks and is now the University of the Ozarks.

Early Twentieth Century

On February 5, 1902, three men (wearing blackface, according to one source) robbed the Bank of Clarksville and, in the process, killed Sheriff John Powers. Exactly one year later, Fred Derham and George Underwood were hanged in Clarksville for the crimes. The third robber, John Dunn, got away and was never charged with his crime. The hanging brought out one of the largest crowds Johnson County had ever seen.

Natural gas was discovered in Johnson County in profitable quantities on November 19, 1921, at a drilling site five miles northwest of Clarksville. In 1929, the Arkansas Western Gas Company built an eight-inch pipe eighty-seven miles long from the Clarksville Gas Field, then the largest in the state, to Fayetteville (Washington County). Natural gas production is still a component of the county’s economy.

The first hospital in the county was Union Hospital, established in 1910. The county is now home to Johnson Regional Medical Center, which has eighty beds for patients.

William Lee Cazort represented the county in both chambers of the Arkansas General Assembly before being elected in 1928 to the first of multiple terms as lieutenant governor.

The Flood of 1927 caused Spadra Creek, which drains into the Arkansas River, to back up and spill over into Clarksville twice that year. However, only after the creek flooded again in 1943 was a flood-control project established to protect the town.

Camp Ozone, a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp, was established in 1933 on the south-central boundary of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forest. Approximately 200 men served at the camp, carrying out the construction of roads and telephone lines, landscaping, and other duties.

World War II through the Modern Era

The 1930s and 1940s saw much school consolidation in Johnson County. In September 1930, the county consolidated six school districts into the Lamar district. In February 1942, six more consolidations were carried out. In June 1949, the county merged four more schools with already consolidated units.

During World War II, the College of the Ozarks hosted a Civilian Pilot Training Program course as well as a naval training facility and classes in the new technology of radar. These programs brought hundreds of new students to the campus, forcing regular classes to relocate.

Johnson County, like other Arkansas River Valley counties, had plantations and farms located in the low bottomlands in the southern region of the counties. Originally, cotton was the largest crop produced, but after cotton production started to decline in the early twentieth century, different fruit crops such as apples, peaches, and pears came to the fore. In 1948, the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville opened an agricultural branch substation in Johnson County specializing in fruit; this substation has been involved in the creation of new peach varieties, and peaches remain an important crop.

In the 1930s, Johnson County also began shipping poultry to other outlets. A poultry processing plant opened in 1952, and the poultry industry is a large employer in the county. Other major employers include the brick industry and the university. The county remains a regional transportation hub, with the Arkansas River, Interstate 40, and various rail lines cutting through it; an airport in Clarksville also serves the area.

Attractions

Johnson County hosts an annual Peach Festival in July. The northern part of the county is covered by a large swath of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forest, which affords opportunities for camping, hiking, and boating. The county features more than two dozen locations listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including a Missouri-Pacific depot in Clarksville; the McKennon House, designed by architect Charles L. Thompson; and the Big Piney Creek Bridge.

For additional information:

Johnson County Historical Society Journal. Coal Hill, AR: Johnson County Historical Society (1975–).

Koenig, Jennifer S. “‘No ma’am, no negroes here at all’: African Americans in Johnson County, Arkansas, 1865–1920.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2008.

Langford, Ella Molloy. Johnson County, Arkansas, the First Hundred Years. Clarksville, AR: Ella M. Langford, 1921.

Overbey, Debra, and Gwen Usery. “Solving the Puzzle . . . Piecing Together African American Ancestral Research in Johnson County, Arkansas.” Johnson County Historical Society Journal 46 (Spring 2020): 31–45.

Rafferty, Milton D. The Ozarks: Land and Life. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2001.

WPA Interview with Pate Newton. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas. Online at http://libinfo.uark.edu/SpecialCollections/wpa/newton.pdf (accessed September 21, 2022).

Jennifer S. Koenig

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Dardanelle and Ivey's Ford, Actions at

Dardanelle and Ivey's Ford, Actions at Fort Smith Expedition (November 5–23, 1864)

Fort Smith Expedition (November 5–23, 1864) Johnson County Courthouse

Johnson County Courthouse Johnson County Historical Society

Johnson County Historical Society Knoxville (Johnson County)

Knoxville (Johnson County) Mickel, Lillian Estes Eichenberger

Mickel, Lillian Estes Eichenberger Native Americans

Native Americans Ozone School

Ozone School Big Piney Creek Waterfall

Big Piney Creek Waterfall  Clarksville Armistice Day Parade

Clarksville Armistice Day Parade  Clarksville Gas Station

Clarksville Gas Station  Clarksville Street Scene

Clarksville Street Scene  Clarksville Street Scene

Clarksville Street Scene  Hartman Catholic Church

Hartman Catholic Church  Johnson County Courthouse

Johnson County Courthouse  Johnson County Map

Johnson County Map  Benjamin Johnson

Benjamin Johnson  Arch McKennon Home

Arch McKennon Home  Montana School

Montana School  Oark General Store

Oark General Store  Oark Post Office

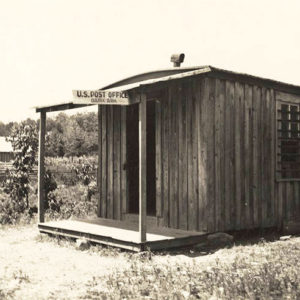

Oark Post Office  Salus Post Office

Salus Post Office

In 1840, Sidney Bumpas Cazort came to Johnson County from North Carolina, landing off a flat boat with his wife and child and two slaves who had refused his offer of freedom. He had friends who had settled nearby and wished to come to Arkansas to hunt. He bought 3,000 acres of what his grandson, Dr. Alan Cazort, always described as “3,000 acres of the worst land in Arkansas.” His three sons farmed the land successfully, but none of the children (24 in all, Alan Cazort being the youngest, born in 1900) chose to farm. Seventy-one acres of that once overfarmed “worst land” has been grazed and fertilized with chicken manure for fifty years and the current owner would like to see a CSA thrive there, growing produce, pastured hogs and chickens, and producing cheeses, wine, and crafts for local markets. The land is, in 2012, two miles off I-40. The owner would offer ten acres rent free for five years as start-up. (Emphasis is not profit but conservation and good nutrition.)