calsfoundation@cals.org

Lawrence County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Walnut Ridge |

| Established: | January 15, 1815 |

| Parent County: | New Madrid, Missouri |

| Population: | 16,216 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 587.53 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

5,592 |

2,806 |

2,835 |

5,274 |

9,372 |

5,981 |

8,782 |

12,984 |

16,491 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

20,001 |

22,098 |

21,663 |

22,651 |

21,303 |

17,267 |

16,320 |

18,447 |

17,457 |

17,774 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17,415 |

16,216 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

15,044 |

92.8% |

| African American |

143 |

0.9% |

| American Indian |

52 |

0.3% |

| Asian |

39 |

0.2% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

12 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

175 |

1.1% |

| Two or More Races |

751 |

4.6% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

357 |

2.2% |

| Population Density |

27.6 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$39,993 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$21,473 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

15.6% |

|

The “Mother of Counties,” Lawrence County once covered a majority of northern Arkansas, an enormous stretch of land ultimately forming thirty-one counties. Present-day Lawrence County straddles the Black River, a natural boundary separating the lowlands of the Mississippi Delta from the foothills of the Ozark Plateau. Long dominated by cotton production, this agricultural county now produces rice, soybeans, corn, and sorghum.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The Osage hunted in what would become Lawrence County, although they had no settlements there. The eastern portion of the county may have been visited in 1541 during a side trip of the expedition of Hernando de Soto. Arkansas became United States territory with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Named for War of 1812 naval hero Captain James Lawrence, the county was created in 1815 as part of Missouri Territory and was the second of five large counties in what became Arkansas Territory in 1819, preceding the creation of Arkansas Territory by four years.

White settlers first inhabited the county’s western regions, traveling on the Black River or, after 1811, over the Military Road. This route, along with the swampy conditions of the east, explains the early settlement concentration in the county’s hilly western half.

The earliest important settlement was at Davidsonville along the Black River. Named for territorial legislator John Davidson, the town served as the first county seat in 1816. Exaggerated tradition claims 3,000 Davidsonville residents before yellow fever ended the settlement. In 1829, the county seat moved to Jackson on the Military Road, and Davidsonville as a community ceased to exist.

Another major settlement was at Smithville near the county’s present western border. Named for businessman Robert Smith, the town became the county seat in 1837, a year after Arkansas attained statehood. In 1838, Smithville witnessed the Trail of Tears as a band of 1,200 Cherokee with “measles and whooping cough among them” passed through the town. Smithville also served as a staging area for local volunteers during the Mexican War (1846–1848). Located at an intersection on the Military Road, Smithville prospered before declining with the loss of its status as the county seat in 1868. Although zinc mining offered hope in the 1890s, the enterprise ultimately failed.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The 1860 federal census reported 8,875 white citizens in the county with three free people of color and 494 enslaved people. At the 1861 Secession Convention, Milton Baber and Samuel Robinson represented the county. While it does not appear that Baber was a slave owner, Robinson owned at least seventeen enslaved people.

During the Civil War, Lawrence County escaped damage while experiencing only a few minor skirmishes near Smithville and the Spring River. Home guards of men incapable of regular service opposed raiding jayhawkers, the area’s only serious threat. Although some residents joined Federal forces, sentiment ran with the Confederacy, and more than seventeen units were organized, most serving in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

During Reconstruction, Lawrence County’s western region became Sharp County, prompting the county seat to be moved from Smithville to the isolated but centrally located Clover Bend in 1868. When Democrats gained control of the county one year later, the seat moved again, this time to the rising commercial center at Powhatan.

Post Reconstruction through the Early Twentieth Century

People were living in the area that is now Powhatan as early as 1816, though it was not platted until 1849. Eventually, the town experienced explosive growth and soon sported mills, shops, and hotels. Because of this growth, it became the county seat in 1869. The first courthouse was built in 1873 and burned in 1885. A Victorian-style replacement was constructed in 1888, using many of the bricks salvaged from the first courthouse in the interior side of the outer walls. Although the county seat until 1963, this once-bustling port began its long decline when bypassed by the railroad and a new bridge at nearby Black Rock, a one-time boomtown of lumber, pearls, and buttons. Today, Powhatan attracts tourists as Powhatan Historic State Park.

Completion of the Iron Mountain Railroad through Walnut Ridge in the 1870s and the Kansas City, Fort Scott, and Memphis Railroad through the adjacent town of Hoxie a decade later shifted the county’s population and economic gravity to the largely uninhabited east. By 1870, legislators divided Lawrence County into eastern and western districts. Walnut Ridge became the eastern seat, while the county seat proper remained at Powhatan. The introduction of screens, pipe wells, and other conveniences coincided with widespread lumbering and agriculture. Timber mill boomtowns sprang up across the east while Walnut Ridge–Hoxie emerged as the county’s economic and population center.

The Walnut Ridge Race War of 1912 was sparked when white workers tried to intimidate African Americans in the county. Designed to scare the Black workers into quitting their jobs, the effort was partially successful.

Served by local newspapers since the 1850s, Lawrence County has been home to the Walnut Ridge–based Times Dispatch since its acquisition by James Bland in 1921. Literary notice came to the county when nationally acclaimed author Alice French (My Name is Masak and The Collaborator: The Trial and Execution of Robert Brasillach), who sometimes wrote under the pen name Octave Thanet, made Clover Bend her winter residence from 1881 to 1909.

As elsewhere, the twentieth century brought to Lawrence County automobiles, planes, radio, and, after World War I, a greater awareness of the world. With cotton leading the way, the county enjoyed economic growth before prices collapsed in the Great Depression. New Deal programs resulted in new bridges and school buildings, and, near Clover Bend, the sale of more than 5,000 acres to the U.S. government for distribution to landless farmers under the Resettlement Administration.

The county was the site of a long-running and bloody feud in the early twentieth century. The Bagley-Ridgeway Feud led to several murders, assaults, and at least one case of arson.

World War II through Modern Era

The construction and operation of the Walnut Ridge Army Airfield during World War II made a huge impact upon the county. This basic army flying school trained thousands of army and marine pilots while transforming the economic landscape of the Depression-blighted area. After the war, a massive warplane salvage facility operated at the site, and in 1947, Southern Baptist College moved to the base from Pocahontas (Randolph County). Today, the site serves as the Walnut Ridge airport and hosts several industries, while the school, now called Williams Baptist University, thrives as a liberal arts institution on a dramatically transformed campus.

In the 1950s, Lawrence County made national news when Hoxie Public Schools willingly desegregated in the face of enormous resistance. The county also drew attention in the 1960 gubernatorial race when Southern Baptist College president Hubert E. Williams challenged popular incumbent Orval Faubus, whose campaign manager owned the Times Dispatch. The county was the site of a brief stopover by the Beatles in 1964. A local radio station, Lake Charles State Park, and a new hospital, library, courthouse, and new highway bypasses mark recent progress.

Small communities in the county include Portia, Imboden, Ravenden, Lynn, Minturn, Sedgwick, Alicia, and Saffell. Strawberry is located near its namesake Strawberry River. Former settlements include College City, which merged with Walnut Ridge after a 2016 vote, and the now abandoned Black community of Driftwood.

Multiple sites at Powhatan Historic State Park are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Telephone Exchange Building, the Ficklin-Imboden Log House, and the Powhatan Methodist Church. Bethel Cemetery is located near the location of the extinct Denton community. The Northeast Arkansas Regional Archives are located in Powhatan.

For additional information:

Johnson, B. H. Harold, ed. History of the Walnut Ridge Army Airfield. Walnut Ridge, AR: Walnut Ridge Army Flying School Museum, 2005.

Lawrence County Historical Journal. Imboden, AR: Lawrence County Historical Society (1996–).

Lawrence County Historical Quarterly. Imboden, AR: Lawrence County Historical Society (1978–1992).

Lawrence County, Arkansas: 1815–2001. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 2001.

Linkpendium Lawrence County. http://www.linkpendium.com/genealogy/USA/AR/Lawrence/ (accessed July 13, 2023).

McLeod, Walter. Centennial Memorial History of Lawrence County. Walnut Ridge, AR: Lawrence County Historical Society, 1980.

Perkins, Blake. “Race Relations in Western Lawrence County, Arkansas.” Big Muddy: A Journal of the Mississippi River Valley 9, no. 1 (2009): 7–21.

Perkins, J. Blake. “Women and American Settlement in Territorial Lawrence County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 75 (Summer 2016): 111–136.

John G. Jacobsen

Williams Baptist University

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Cache River Bridge

Cache River Bridge  Hoxie Glee Club

Hoxie Glee Club  Lake Charles State Park

Lake Charles State Park  Lawrence County Courthouse

Lawrence County Courthouse  Lawrence County Courthouse

Lawrence County Courthouse  Lawrence County Map

Lawrence County Map  James Lawrence

James Lawrence  Portia Lumber Company

Portia Lumber Company  Powhatan Courthouse

Powhatan Courthouse  Scott Cemetery

Scott Cemetery  Southern Baptist College Chapel

Southern Baptist College Chapel  Walnut Ridge Army Air Field

Walnut Ridge Army Air Field  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School Fighter Planes

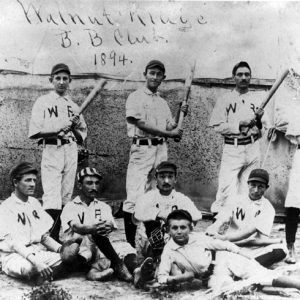

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School Fighter Planes  Walnut Ridge Baseball Club

Walnut Ridge Baseball Club  Walnut Ridge Laundry

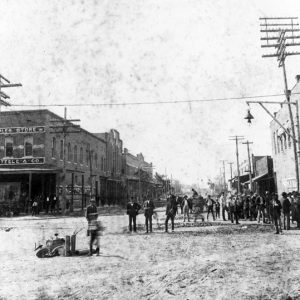

Walnut Ridge Laundry  Walnut Ridge Street Scene

Walnut Ridge Street Scene  Walnut Ridge Street Scene

Walnut Ridge Street Scene  Williams Baptist College Fine Arts Building

Williams Baptist College Fine Arts Building

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.