calsfoundation@cals.org

Lee County

| Region: | Southeast |

| County seat: | Marianna |

| Established: | April 17, 1873 |

| Parent counties: | Crittenden, Monroe, Phillips, St. Francis |

| Population: | 8,600 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 599.81 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

| 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

13,288 |

18,886 |

19,409 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

24,252 |

28,852 |

26,637 |

26,810 |

24,322 |

21,001 |

18,884 |

15,539 |

13,053 |

12,580 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10,424 |

8,600 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

3,465 |

40.3% |

| African American |

4,663 |

54.2% |

| American Indian |

39 |

0.5% |

| Asian |

13 |

0.2% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

2 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

121 |

1.4% |

| Two or More Races |

297 |

3.5% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

216 |

2.5% |

| Population Density |

14.3 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$29,681 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$16,968 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

22.1% |

|

Located in the Delta, Lee County is bounded on its east by the Mississippi River. Two navigable rivers, the St. Francis and the L’Anguille, flow through the county. Marianna, the county seat and largest town, sits on the L’Anguille. Though the county’s fertile land and timber resources built its rural agricultural landscape, its emphasis on agriculture translated in a severe population decline as agricultural modernization progressed in the middle of the twentieth century.

European Exploration and Settlement

Hernando de Soto and his men were probably the first Europeans to enter what is now Lee County in August 1541. The expedition likely descended the St. Francis River and entered the chiefdom of Quiguate, which the Spaniards described as the largest of the fortified Native American towns they visited in La Florida. The Grant Site, a Kent phase archaeological site, is the likely remnant of the Quiguate chiefdom.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, French explorers, hunters, and their American counterparts entered the wilderness via the Mississippi, L’Anguille, and St. Francis rivers. One traveler on the Mississippi in the early 1790s reported a vessel “laden with Bear and Buffaloe Meat, taken on the St. Francis River.” Permanent settlers soon replaced hunters; one of the first was Sylvanus Phillips, who moved near the mouth of the St. Francis in the late 1790s. Near Phillips, according to an 1808 account, were twelve other families with an “abundance of fine looking cattle.” Phillips later became the namesake for Phillips County and founded Helena (Phillips County), named for his daughter. In 1818, John Patterson, Phillips’s stepson, moved farther into the frontier to a hunting cabin south of present-day Marianna, at a site later called Patterson’s Branch. Patterson, according to lore, was “the first Anglo-Saxon child born in what is now Arkansas,” around 1800.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In 1815, growth in the lower St. Francis was made possible by federal surveys that became the basis for the Public Land System in the Louisiana Purchase. Survey teams worked west from the mouth of the St. Francis and north from the Arkansas River, meeting at what is now the corner of Lee, Phillips, and Monroe counties. The historic importance of the point was recognized in 1926 by the L’Anguille Chapter of the Daughters of American Revolution with a stone marker. Although difficult to access until the early 1970s, it became the Louisiana Purchase Historic State Park in 1961 and a National Historic Landmark in 1993.

Initially, most settlements, such as Walnut Bend (post office established in 1838) and Council Bend (1846), were confined to the Mississippi River, but within a few years, settlers moved into the interior. In 1848, Walnut Ridge (changed to Marianna in 1852) was founded along the L’Anguille by Colonel Walter H. Otey. In 1855, Moro was founded west of Marianna. LaGrange, south of Marianna, established a post office in 1856. About 1858, Marianna moved three miles south to a point where the L’Anguille was declared navigable year-round. Many of the settlers arrived with cotton seed and slave labor. One settler, in a 1920 interview, recalled moving from Alabama in 1859 to near present-day Aubrey with 200 friends, relatives, and slaves.

Civil War through Reconstruction

As the Civil War began, the region raised several companies of men for the Confederacy, but no major battles were fought in what is now Lee County. Skirmishes between Union soldiers and Confederate loyalists around La Grange and Marianna were common in 1862. In June and July 1863, soldiers under the Confederate leadership of Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke and Major General Sterling Price stopped in Moro en route to attack Union-occupied Helena. Despite the tensions between Union occupiers and locals, a cotton economy, although illegal, thrived.

After the war, Confederate veterans returned. At least two prominent Confederate generals owned plantations in the future Lee County: Daniel Chevilette Govan and Gideon Pillow. Lee County’s proximity to Memphis, Tennessee, a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity, and scattered reports suggest that the Klan influenced the area’s politics and economy. But Republican Reconstruction governor Powell Clayton and State Militia Commander Daniel Phillips Upham suppressed Klan activities in the Militia War (1868–1869).

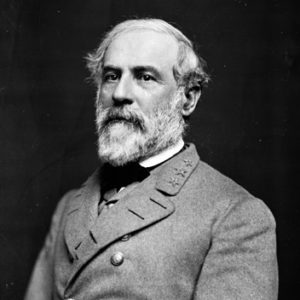

By 1870, Marianna’s population had grown to at least 150, and the town was vying to be the seat of a new county. In April 1873, legislation to create Lee County was moved through the General Assembly by William Furbush, an African-American Republican who represented Phillips County in the state House. The county incorporated parts of four neighboring counties—Phillips, Monroe, St. Francis, and Crittenden. Furbush most likely selected “Lee,” honoring General Robert E. Lee, to show his allegiance to Democratic backers around Marianna.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

After an appointment to the office of sheriff by Republican Governor Elisha Baxter, Furbush orchestrated a fusion political compromise between Lee County’s economically powerful Democratic minority and its Black Republican majority. The parties shared political power and offices and avoided the most violent political confrontations. However, in 1878, when Democrats intimidated Republicans during elections, the tenuous alliance ended, paving the way for a Democratic sweep of nearly all the county’s races. Furbush switched parties to become the Democratic candidate for state representative in 1878. Upon his election, Furbush became the first African American from that party in the General Assembly.

As in other parts of the South, populism emerged as a force in Lee County in the 1880s and 1890s. One of the first movements began in February 1882 with the arrival of a charismatic African American named John W. Niles. Niles arrived from the all-Black town of Nicodemus, Kansas, which was founded in 1877 during the Exoduster movement, in which Southern African Americans fled to Kansas as Reconstruction ended. Niles, under the banner of the Indemnity Party, preached a message of indemnity (reparations for former slaves) and the dream of Progress, an all-Black town separate from whites in northern Lee County. The ideas resonated with the black sharecropping majority and the waves of black immigrants streaming in from the southeast. The Indemnity Party faded following the arrest of Niles in June 1882 for selling liquor without a license.

In 1888, populist candidates ran close races against Democrats across the state. The Union Labor/Agricultural Wheel’s candidate for the First Congressional District was Lewis Porter Featherstone. Featherstone, a white resident of Forrest City (St. Francis County) and president of the State Wheel, was declared the winner after a congressional investigation found the Democratic incumbent, William Henderson Cate, had won through fraud. Cate regained his seat in the next election. In 1891, Lee County was the site of a cotton pickers’ strike. The Colored Farmers’ Alliance, and a splinter group, the Cotton Pickers League, planned for pickers to strike across the cotton South unless planters raised pay to one dollar from fifty to sixty cents per 100 pounds of cotton picked. However, the only strike to emerge was in Lee County. Violence ensued with the deaths of two Black pickers, a white plantation manager, and fifteen strikers. The violence hurt the credibility of the Colored Farmers’ Alliance, reducing its membership and authority.

Steamboats—such as the Plow Boy, St. Francis, Mollie Hamilton, Nettie Johnson, and Lee Line—made regular trips carrying bales of cotton, passengers, and other goods between Memphis and towns on the St. Francis and L’Anguille rivers until railroads began to supplant river transit in the early 1880s. First, between 1880 and 1881, the Helena and Iron Mountain Railroad linked Marianna with La Grange and Helena to the south and Marianna with Haynes (Lee County) and Forrest City in the north. The Missouri and North Arkansas, the second line in the county, was an ambitious project that connected Joplin in the Missouri Ozarks with Helena. Completed in 1909, it ran through western Lee County. Locals joked that the initials “MNA” stood for “May Never Arrive,” but the line was a boon to Moro and a catalyst for two new towns—Aubrey and Rondo. The third and final railroad, a Missouri Pacific line, was completed by 1913. Known as the Marianna Cutoff, it ran from Memphis through the plantation towns of Soudan and Brickeys to Marianna. Its popularity was reflected in the music of the times when the Memphis Jug Band recorded “Mary Anna Cut Off” in 1930. Today, only the Iron Mountain route is still in use. Other settlements served by railroads in the county include Raggio.

As the county’s cotton economy grew, so did the desire to build levees for flood control. Captain Henry Newton Pharr, a planter and engineer living at La Grange, initiated that quest in 1891. In 1893, the General Assembly approved the St. Francis Levee District, which encompassed Lee, St. Francis, Crittenden, Craighead, Poinsett, and Mississippi counties and part of Phillips County. In the late 1890s, the Mississippi River Commission constructed a levee at Walnut Bend between the Mississippi and St. Francis rivers to prevent the St. Francis from forming a cutoff into the Mississippi River.

Numerous incidents of racial violence occurred in the county in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Dave Ramsey was killed in 1881 for allegedly attempting to rape a white girl. After allegedly committing arson, Jesse Howard was lynched two years later. The 1891 Cotton Pickers Strike led to at least seventeen deaths. Additional race-based lynchings took place in the county in 1900 and 1919.

Early Twentieth Century

By the early twentieth century, economic development had visibly altered the county’s landscape. The growth of agriculture, railroads, and a Southern hardwood forest industry shrank the county’s vast old-growth forests from virtually unbroken in 1870 to “chronically cut over” by the early 1930s. Conservation efforts on Crowley’s Ridge, headed by the Soil Conservation Service, in the 1930s resulted, nearly three decades later, in the St. Francis National Forest—one of the nation’s smallest at 22,600 acres—in 1960. Hunters today know the St. Francis National Forest and the 200-acre Lee County Wildlife Management Area near Haynes for their abundant deer, wild turkey, squirrel, rabbit, quail, duck, and dove. The Mississippi River State Park, utilizing part of the St. Francis National Forest, began operations in 2009.

On April 16, 1927, at 8:00 p.m., the levee at Whitehall broke, allowing water from the Mississippi River to flood eastern Lee County. Backwaters from the St. Francis River were already flooding the region as part of the larger Flood of 1927, but the break added to the misery. The St. Francis Levee Board contracted the steamer the Henry Lee to assist government rescue boats along the St. Francis River. For about ten days, the boats rescued people and livestock, taking many to a dry Marianna.

As cotton production expanded, the state Agricultural Extension Service established the Cotton Branch Experiment Station at Marianna in 1926 as one of the three original branches. Carl Avriette Moosberg created an early blooming cotton variant at the station in the 1950s. Besides cotton, western Lee County became a significant producer of rice by the mid-1920s. The county continues to be major grower of cotton, rice, wheat, corn, sorghum, and soybeans.

Like the rest of the rural South, Lee County’s agricultural economy underwent several dramatic changes in the twentieth century and beyond. Throughout the century, the county’s rural agricultural population abandoned working for shares and sought equality and better financial opportunities in Northern and Southern cities. Agricultural production adapted with mechanization as the county’s population continually fell—from 28,852 in 1920 to 8,600 in 2020, a decline of seventy percent.

The county constructed a courthouse in 1939 with support from the Public Works Administration. The structure and a statue of Robert E. Lee located on the lawn are both listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Modern Era

The late 1960s and 1970s in Lee County, like a century before, marked a period of momentous change as race relations were strained in a series of incidents. In 1969, conflicts emerged over the creation of the Lee County Cooperative Clinic, a Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) program, headed up by Olly Neal Jr., that provided medical care to the county’s poor, most of whom were Black. Tensions rose again as African Americans demanded economic and political equality by staging a boycott of white businesses in downtown Marianna (June 1971 to July 1972), and Black students boycotted Lee Senior High School from January to May 1972. These events sparked a renewal of Black political participation after nearly a century of disfranchisement and intimidation. In 1990, Lee County elected Roy C. “Bill” Lewellen, its first Black state senator since the 1870s, and in 1994, Robert Taylor was elected Marianna’s first Black mayor. Rodney Slater, a native of Marianna, served as Secretary of the Transportation in the administration of President Bill Clinton.

In the fall of 1970, under pressure from the federal government, the county’s school board abandoned its “freedom of choice plan” and integrated the public schools; however, Lee Academy, the new private school, siphoned a significant portion of the white school-age children, leaving the public schools virtually segregated to this day.

Although historically it has been one of the poorest counties in the country, Lee County saw its poverty rate improved throughout the twentieth century. In 1969, 50.3 percent of all families in Lee County lived in poverty. By 1979, that number had fallen to 36.6 percent. The number rose again to 39.1 percent by 1989, but by 1999, only 24.7 percent of families were living in poverty. By the 2010 census, however, the percent of the population living below the poverty line had risen to 42.6. By 2021, this percentage had fallen to 36.8.

Two new plants—Douglas and Lomason (later Camaco), an automobile seat frame manufacturer, and P. M. Manufacturing, a clothing manufacturer—opened in 1960 and 1967, respectively. In 1970, a Coca-Cola bottling plant opened. By 1983, Camaco was the only manufacturer left in the county; however, in January 2007, Camaco announced it would shut down in March. In 1977, the W. G. Huxtable Pumping Station, one of the world’s largest, was completed seven miles southeast of Marianna to prevent flooding in the St. Francis bottomlands. A correctional facility, the East Arkansas Regional Unit at Brickeys, opened in 1992, and the Marianna/Lee County Airport expanded significantly in 2004. However, agriculture dominates Lee County’s economy: fields of soybeans and rice are now as common as king cotton. In 2001, the county’s only remaining cotton gin—McClendon, Mann & Felton—expanded its Marianna operation to accommodate record harvests efficiently, and in 2005, the Cotton Branch Experiment Station was renamed the Lon Mann Cotton Research Station and added a new headquarters, the Dan Felton Jr. Building.

For additional information:

Adler, William M. Land of Opportunity: One Family’s Quest for the American Dream in the Age of Crack. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1995.

Apple, Nancy, and Suzy Keasler, eds. History of Lee County, Arkansas. Dallas: Curtis Media Group, 1987.

Couto, Richard A. Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Round: The Pursuit of Racial Justice in the Rural South. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Neal, Olly, Jr., as told to Jan Wrede. OUTSPOKEN: The Olly Neal Story. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2020.

Tri-County Genealogy. Marvell, AR: Tri-County Genealogical Society (1986–).

Wintory, Blake. “William Hines Furbush: African-American, Carpetbagger, Republican, Fusionist, and Democrat.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 63 (Summer 2004): 107–166.

Blake Wintory

Little Rock, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Lee County Courthouse

Lee County Courthouse  Lee County Courthouse

Lee County Courthouse  Lee County Courthouse

Lee County Courthouse  Lee County Map

Lee County Map  Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee  Marianna Park

Marianna Park  Marianna Arch

Marianna Arch  Marianna Street Scene

Marianna Street Scene  Marianna Street Scene

Marianna Street Scene  Marianna Street Scene

Marianna Street Scene

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.