calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA)

aka: Arkansas Equal Suffrage Central Committee (AESCC)

aka: State Woman's Suffragist Association

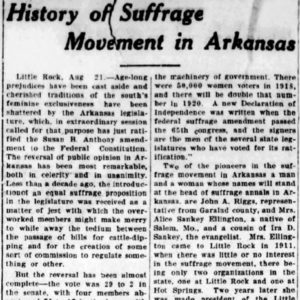

The post–Civil War era saw the beginnings of major social change in Arkansas concerning race relations and civil rights, temperance, and voting rights for women. Female leaders from other states, often with legal backgrounds, came to Arkansas to advocate for women’s suffrage. They helped set up organizations such as the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which was designed to advocate for suffrage in the Arkansas General Assembly, to encourage related organizations and activities, and to attract press coverage. Two different AWSA organizations, one that existed from 1881 to 1885, and another that began in 1914, were instrumental in promoting women’s suffrage in Arkansas. Because of the suffragists’ work in these and companion organizations, in 1918, Arkansas became the first non-suffrage state to allow women to vote in primary elections. Arkansas also became the twelfth state to ratify the women’s suffrage amendment that would, in 1920, mandate equal voting rights nationally.

At the state constitutional convention in 1868, voting for Arkansas women was proposed. However, the idea was eventually passed over partly because of the fear that it would encourage “revolutions in families.” There were also general concerns about politics and suffrage. The Morning Republican in Little Rock (Pulaski County) noted in June 1868 that it had earlier “expressed our warm sympathy with the cause of women’s rights.” The article cautioned, however, that this sympathy would be seen as a political “fatal mistake on the part of the leaders of the movement in affiliating with the [D]emocratic party.” Connecting the civil rights and women’s suffrage movements, the newspaper article supported civil rights advocate Frederick Douglass and quoted him as saying, “While the Democratic party is disenfranchising the negro, and woman, too, the Republican party is enfranchising the negro at least, and, I think, is largely in favor of the enfranchisement of woman.” After the constitutional convention, pro-suffrage speakers such as Phoebe Wilson Couzins visited Little Rock. The January 4, 1870, Morning Republican noted that the speaker from neighboring Missouri provided “an eloquent lecture, full of brilliant and sparkling thoughts.”

By September 1881, former Massachusetts resident Eliza (“Lizzie”) A. Dorman Fyler formed and became president of the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association in Eureka Springs (Carroll County). The group’s function was to advocate for “such legislation as shall secure to woman all the rights and privileges which belong to citizens in a free republic.” Fyler was considered to be a good candidate to spearhead a women’s suffrage movement partly because of prior experience elsewhere. As historian Elna C. Green noted, Fyler had been a temperance worker as well as a lawyer, “and was nearly a generation ahead of most southern women in the critical experiences that produced suffragism.” By 1885, she would become known as the first woman to practice law in the state, though there is a dispute about whether she was technically a member of the bar.

While advocating for suffrage rights, Fyler was concerned that the women who voted should be literate. The Massachusetts newspaper the Springfield Republican reported that Fyler told the American Woman Suffrage Association in 1885 that in Arkansas, there was “an alarming amount of illiteracy at the polls.” She advocated for an educational qualification for suffrage in Arkansas, similar to what was in place for the better-educated citizens of her native Massachusetts.

Fyler dissolved the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association in October 1885, the year in which she herself died at the age of thirty-five. Vestiges of the suffrage group’s goals continued, however, without the Carroll County group. The January 26, 1890, Arkansas Gazette announced a meeting of a group with a nearly identical description, the Arkansas Woman’s Suffrage Association, headed by Clara McDiarmid in Little Rock. Its goal was to elect delegates to a national suffrage convention. McDiarmid had organized the group in 1888, apparently without knowing about the earlier Fyler organization. McDiarmid’s new group sometimes went by other names, such as the State Woman’s Suffragist Association.

Ongoing women’s club and suffrage activity increased in the state as the temperance movement, too, picked up strength. The Political Equality League in Little Rock, formed in 1911, especially created momentum for suffrage, establishing branches in Hot Springs (Garland County), Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Fayetteville (Washington County), and other cities by 1914. That was the year that the next Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association formed in Little Rock’s Marion Hotel in October. Its president was Alice S. Ellington. Its goals were to support a constitutional suffrage amendment for Arkansas primary voting as well as to support general women’s suffrage.

In 1915, the AWSA and the Political Equality League financially supported the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage in its efforts for a national suffrage amendment. By the time the National American Woman Suffrage Convention was held in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in September 1916, AWSA vice president Florence Brown Cotnam was scheduled to speak on “Dixie Night,” an event that highlighted southern women’s views and accomplishments related to suffrage.

Despite the support of the AWSA, the Political Equality League, and other related groups, there were disappointments regarding a women’s suffrage amendment in the Arkansas General Assembly in 1915. It passed both houses of the legislature, but it was eventually not presented to voters because of a law that limited such ballot amendments to three.

In 1917, growing suffrage support, the AWSA’s work, and the work of the Political Equality League bore fruit. A bill to allow Arkansas women to vote in primaries passed both houses of the legislature. Governor Charles Brough then signed the measure into law. That legislative decision led the AWSA to reorganize itself into the Arkansas Equal Suffrage Central Committee (AESCC) led by Cotnam. The AESCC would show women how to work within established political parties rather than being strictly nonpartisan. It also supported the national suffrage campaign.

About 40,000 Arkansas women voted in the 1918 primary. U.S. senator Joseph T. Robinson said, “They gave honest thought to their votes, and the best women of the state went at the matter as a duty they owned and a privilege they had long desired.”

The Nineteenth Amendment, which allowed women to vote, passed in the Arkansas General Assembly in July 1919. It became law nationally in 1920, and the AESCC became the Arkansas League of Women Voters. The group that had started as the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association thus evolved and continued to educate new voters about their rights and responsibilities.

For additional information:

Cahill, Bernadette. Arkansas Women and the Right to Vote: The Little Rock Campaigns, 1868–1920. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

Green, Elna C. Southern Strategies: Southern Women and the Woman Suffrage Question. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Moneyhon, Carl. Arkansas and the New South, 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Taylor, A. Elizabeth. “The Woman Suffrage Movement in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Spring 1956): 17–52.

Williams, C. Fred, S. Charles Bolton, Carl H. Moneyhon, and LeRoy T. Williams, eds. A Documentary History of Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2013.

Jeanne Norton Rollberg

Little Rock, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Florence Cotnam

Florence Cotnam  Clara McDiarmid

Clara McDiarmid  Suffrage Article

Suffrage Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.