calsfoundation@cals.org

Urban Renewal

Urban renewal is the generic term given to the redevelopment of land in urban areas. In the United States, it is largely associated with post–World War II federal housing policy stemming from the passage of the federal Housing Act of 1949. Though ostensibly designed to beautify cities by getting rid of old and decrepit housing stock and replacing it with new and modern homes, these projects typically had a racial component. This has led to accusations that urban renewal programs consciously manipulated residential areas to establish, perpetuate, and/or extend geographical racial segregation in city neighborhoods. As Little Rock (Pulaski County) is Arkansas’s largest urban area, its experience of urban renewal typifies the experience of many other urban areas in the South and also in the nation, though it was by no means the only city in Arkansas to experience urban renewal.

Little Rock’s housing patterns did not always look the way they do today. From its earliest days, the city developed a reputation for having a more progressive racial climate than surrounding areas. The scarcity of labor in the pre–Civil War period meant that skilled black slaves were in demand and could bargain for better terms of employment and for more freedoms. Some were allowed to “hire out” their labor and keep a portion of their wages, and some even purchased their own living quarters.

As a result, even during slavery, racially mixed housing patterns in the city were established. In Little Rock, unlike in many other cities, there were no laws to prohibit blacks and whites living in the same area. As the city grew, however, discernible black residential areas began to develop just off West 9th Street’s downtown black business district and toward the east of the city. This was due largely to economic constraints, the location of black institutions and businesses, and the practicalities of finding security in numbers. Yet there were also many “pepper and salt” (that is, mixed black-and-white) neighborhoods. As late as 1941, a study sponsored by the Greater Little Rock Urban League noted, “While Negroes predominate in certain sections…in Little Rock, there are…no widespread…‘Negro sections’ [of residence].”

The passage of the federal Housing Act of 1949 changed that. The act, designed to modernize cities in the post–World War II era, was used by Little Rock to begin a racial redistricting of the city. It initially held out the promise of better conditions for Little Rock’s black population by eradicating poor housing and replacing it with new public housing units. But white city planners had other ideas. Their focus was less on improving the conditions of the black community and more on using funds to perpetuate and even extend segregation in the city. B. Finley Vinson, head of the Little Rock Housing Authority (LRHA) and its slum clearance and urban redevelopment director, freely admitted that “the city of Little Rock through its various agencies including the housing authority systematically worked to continue segregation.”

The intent of city planners to use federal housing policy as an instrument for achieving residential segregation was evident when black areas of residence were seemingly targeted for redevelopment because of their close proximity to white neighborhoods rather than their slum status. For instance, the first part of the city designated as a “blighted area” for demolition and clearance was a ten-block area of homes at the heart of the downtown Little Rock black community in the Dunbar neighborhood. Blacks viewed the area, resident Lola S. Doutherd said, as “the choicest area of the Negro residential section….It contains many churches, schools, completely modern homes, paved paid out streets, and it is within easy walking distance to the business section of the city.” Doutherd alleged that “coercion and intimidation” were used by the LRHA to force black residents to sell their properties in the area. The LRHA “threatened the owners by telling them if they did not sell at the appraised price, they would be ordered in court and given less, or evicted from their homes.”

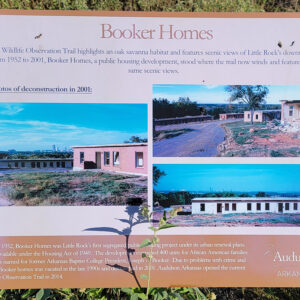

While the LRHA evicted black residents downtown, it built black public housing on the edge of the city limits as far away from white neighborhoods as possible. The first public housing projects built under the redevelopment plans were the 400 units of Joseph A. Booker Homes in the far southeastern city limits. Other housing projects followed a similar pattern. By 1990, the major public housing projects of the 1950s had ninety-nine percent black occupancy. Predominantly white areas had only five percent of the city’s public housing units, and there were none at all in the far west of the city.

Given this residential gerrymandering, it is hardly surprising that Little Rock’s first response to the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas school desegregation decision was to build two new geographically segregated high schools in the city. In addition to the existing centrally located white Central High and black Dunbar High, Horace Mann High was built in the predominantly black eastern part of the city, and Hall High was built in the predominantly affluent white western part of the city. From the outset, this encouraged the school district to grow in a geographically segregated manner hand-in-hand with city housing policy.

City residents clearly understood what was happening. A 1964 report by the Greater Little Rock Conference on Religion and Race titled, “Confronting the Little Rock Housing Problem: An Alarming Trend,” noted: “The evidence indicates an advanced trend toward complete racial segregation in housing.” At one meeting of concerned citizens, Little Rock housing director Dowell Naylor was asked bluntly, “Is development in housing in Little Rock drawing racial groups together or silently drawing them apart?” Naylor answered, “Drawing them apart.”

Private-sector practices bolstered public policy in creating a geographically segregated city. “Restrictive covenants” were placed in property contracts to prevent resale to blacks. “Redlining” was used by banks and mortgage brokers to deny loans to black families in white areas of residence. Real estate agents used “racial steering” to show white purchasers homes only in areas of white residence, and black purchasers homes only in areas of black residence. In a maneuver known as “block-busting,” real estate agents sometimes deliberately moved black families into centrally located white blocks of residence. Whites moving out were sold more expensive homes in the growing Little Rock western suburbs, while blacks paid high prices for the limited housing stock left available to them.

Meanwhile, efforts by black families to move into white areas were resisted. In September 1965, attorney John Walker purchased a home in the all-white Broadmoor addition in western Little Rock. A can of paint was hurled through his front window, and his shrubbery was set on fire even before his family moved in. After they moved in, white neighbors ostracized them. As one resident put it, “The policy in Broadmoor is to ignore the Walkers. If no one says anything to them I think it will be only a matter of time before they move somewhere else.” The resident was right. Walker moved north to the University Park development not long after. The University Park area was one of the rare instances in which middle-class blacks were able, through a concerted effort, to preserve a black presence in western Little Rock.

In 1966, the Arkansas Gazette ran a series of articles by Jerol Garrison that assessed trends in race and residence. An editorial summed up the findings: “There has been a clear trend, a trend toward the concentration of Negroes in one large area centrally located, and of whites in newer residential areas to the west….The movement is away from the ‘pepper and salt’ pattern in which Negro and white neighborhoods are interspersed.” It concluded, “In such circumstances racial segregation becomes more obvious and all-encompassing, especially when schools desegregated by law become largely segregated in fact simply because of prevailing residential patterns.”

In 1971, when busing threatened to overturn the effects of residential segregation by forcing cross-city transportation of students to ensure integrated public schools, Little Rock witnessed a sprouting of new private schools. Their locations once again largely mirrored the city’s segregated housing patterns.

Since the 1950s, Little Rock’s policy of urban renewal, alongside other factors, has created a more residentially segregated city. In the twenty-first century, two halves define the city. One, to the east of Interstate 30 and to the south of Interstate 630, is predominantly black, Latino, and poor. The other, to the west of Interstate 430 and to the north of Interstate 630, is predominantly white and more affluent. Although some would insist that this came about through a series of individual choices in the housing market, there is strong evidence (including material introduced into the 1982 Little Rock Schools desegregation lawsuit and upheld in the federal courts) to suggest that the city’s current geographically segregated housing patterns have been consciously created by public policy, with private-sector collusion, since the 1950s.

For additional information:

Johnson, Ben F., III. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Kirk, John A. “Housing, Urban Development and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the Post–Civil Rights South.” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Society and Culture 8 (Winter 2006): 47–60.

———. “‘A Study in Second-Class Citizenship’: Race, Urban Development and Little Rock’s Gillam Park, 1934–2004.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 64 (Autumn 2005): 262–286.

Kirk, John A., and Jess Porter. “The Roots of Little Rock’s Segregated Neighborhoods,” Arkansas Times, July 10, 2014, pp. 12–16. Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/the-roots-of-little-rocks-segregated-neighborhoods/Content?oid=3383298 (accessed November 17, 2021).

Mapping Renewal. University of Arkansas at Little Rock. https://mappingrenewal.ualr.edu/stories.html (accessed November 17, 2021).

Roher, Acadia. “Urban Renewal in Little Rock’s Dunbar Historic Neighborhood: A Walking Tour.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2021.

Semuels, Alana. “How Segregation Has Persisted in Little Rock.” The Atlantic, April 2016. http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/04/segregation-persists-little-rock/479538/ (accessed November 17, 2021).

Tell-Hall, Nancy. “Little Rock Urban Renewal PROJECT ARK-4: The Demise of West Rock, Arkansas, 1884–1960.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2019.

Walters, Martha. “Little Rock Urban Renewal.” Pulaski County Historical Review 24 (March 1976): 12–16.

John A. Kirk

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Gillam Park

Gillam Park Politics and Government

Politics and Government Racially Restrictive Covenants

Racially Restrictive Covenants White Flight

White Flight World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Booker Homes Sign

Booker Homes Sign

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.