calsfoundation@cals.org

Logan County

| Region: | Northwest |

| County Seats: | Booneville, Paris |

| Established: | March 22, 1871 |

| Parent Counties: | Franklin, Johnson, Scott, Yell |

| Population: | 21,131 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 709.12 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

14,885 |

20,774 |

20,563 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

26,350 |

25,866 |

24,110 |

25,967 |

20,260 |

15,957 |

16,789 |

20,144 |

20,557 |

22,486 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

22,353 |

21,131 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

18,826 |

89.1% |

| African American |

232 |

1.1% |

| American Indian |

241 |

1.1% |

| Asian |

328 |

1.6% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

8 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

225 |

1.1% |

| Two or More Races |

1,271 |

6.0% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

640 |

3.0% |

| Population Density |

29.8 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$41,466 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$21,491 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

18.7% |

|

Logan County, located in the Arkansas River Valley in northwestern Arkansas, is one of ten counties in Arkansas having two county seats: Paris and Booneville. Other incorporated communities in the county are Magazine, Blue Mountain, Caulksville, Ratcliff, Subiaco, Scranton, and Morrison Bluff.

Although Logan County was not created until 1871, the area that is now Logan County has had a significant impact on the development of western Arkansas dating from territorial days. Some of the oldest settlements in western Arkansas were located in what is now Logan County. During territorial days and throughout the century, Roseville, a busy port on the Arkansas River, played a vital role in river transportation of goods and passengers. Settled around 1830, Booneville was the only trading center between Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and Dardanelle (Yell County). The diverse contributions of Logan County in transportation, agriculture, timber production, coal mining, natural gas production, and industry have spurred the economic growth of the region. Logan County has been primarily an agricultural area with small farms growing crops of cotton and corn, raising beef cattle, and producing poultry. Other resources that have contributed to its economy are timber, coal, and natural gas. During the latter part of the 1900s, tourism began to play an important role in the economy when Mount Magazine State Park and other recreational facilities were developed.

Pre-European Exploration through Early Statehood

For 10,000 years various groups explored the wilderness west of the Mississippi River, collecting wild resources and establishing campsites but building no permanent homes. Roughly 1,000 years ago, such groups began spending more time cultivating domestic plants, particularly corn, and settled into more stable, permanent residential communities. Pottery, weapons, and other implements have been found representing these many groups, and some mounds remain from these occupations. Unfortunately, the county has been ravaged by amateur collectors of Native American artifacts, destroying sites that could have been valuable sources for archaeological study. A series of treaties with different tribes gradually removed their claim to the land, opening western Arkansas for white settlement. The early to mid-nineteenth century saw settlers from states east of the Mississippi River pouring into western Arkansas and establishing small farms and communities.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The antebellum controversy over slavery had little effect on residents of western Arkansas, which was not home to the large plantations present in the eastern and southern part of the state. However, when secession of the Southern states became imminent, residents began to line up in favor of either the Union or the Confederacy. After Arkansas joined the Confederacy and the Civil War broke out, Logan County supplied troops to both the Confederate and Union armies. Although military action in the county was limited to a minor skirmish or two during the war, the Logan County area was ransacked by both armies foraging for supplies while lawless bushwhackers raided and terrorized the area. Engagements took place at Haguewood Prairie and Roseville. The population suffered tremendous hardships, and families who could afford it moved to other states for the duration of the war.

After the Civil War ended, Reconstruction began in the South to aid in the recovery of the devastation of the war years. During this period, Logan County was created as Sarber County from parts of Johnson, Yell, Scott, and Franklin counties. John Sarber, a Republican senator from Johnson County and a veteran of the Union army, introduced the bill creating the county in the state legislature at the urging of citizens of Clarksville, the Johnson County seat. The new county was proposed to counteract growing support for the relocation of the Johnson County seat from Clarksville (Johnson County) to Spadra (Johnson County) on the Arkansas River. Part of Johnson County lay south of the river, and its residents found it inconvenient and costly to ferry across and proceed to Clarksville, four miles north of the river. Changing the location from Clarksville to Spadra would give them a more convenient access to the county seat. Not wanting to lose the county seat, citizens of Clarksville proposed creating a new county with that part of Johnson County south of the Arkansas River. However, that area was not large enough for a new county. Additional land would have to be acquired from the neighboring counties. A deal was made with neighboring counties of Scott, Franklin, and Yell to grant parts of these counties to form a new county. Senator Sarber presented the proposal for a new county to the legislature, and an act was passed on March 22, 1871, creating “a county called Sarber.”

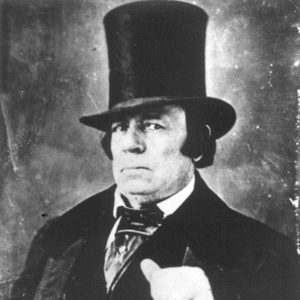

After commissioners were appointed to designate a site for the county seat of Sarber County, a heated controversy arose over the location chosen. After two proposals were rejected, a site was selected on farmland near Short Mountain. A courthouse square was laid out, and the town of Paris grew up around it. Three men were lynched in the county on August 6, 1874, for allegedly stealing horses. By 1875, Reconstruction government had ended, and Democrats regained the dominant role in Arkansas government. Sarber County Democrats vehemently opposed the county being named after Sarber, whom many considered a Yankee carpetbagger. The legislature was asked to change the name to Logan County in honor of James Logan, an early settler. On December 14, 1875, the name was changed to Logan County, with Paris named as the official county seat.

At this time, the Arkansas Central Railroad began building a rail line from Fort Smith to Dardanelle through north Logan County. To establish industrious farming communities along the rail line, the company embarked on a campaign to entice German Catholic immigrants to settle along the line because the immigrants had proven to be hard-working and successful farmers in other states. Farmland was offered to the immigrants at attractive prices, and the railroad granted land to St. Meinrads Abbey in Indiana for a Catholic mission in Logan County. German settlement along the rail line grew quickly, resulting in the towns of Ratcliff, Subiaco, and Scranton.

The Gilded Age through the Early Twentieth Century

In 1884, Dan Oliver was killed by a lynch mob after he was accused of assaulting a white woman. In 1899, the Choctaw, Oklahoma, and Memphis Railroad completed a rail line between McAlester, Indian Territory, and Little Rock (Pulaski County). Constructed through southern Logan County, the line completed a link between Memphis, Tennessee, and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, providing a south-central route for transcontinental rail service for freight and passengers. Booneville was selected as the division point for crew changes and locomotive servicing.

In 1901, Logan County was divided into two judicial districts with a county seat in each district. Paris became the seat for the Northern Judicial District and Booneville for the Southern Judicial District. A courthouse was mandated for each district for the deposit of all records of the district; however, pre-1901 records remained in the Paris courthouse.

Although criminal activity has created few problems for Logan County, an early-twentieth-century homicide case received special attention because the outcome of the trial resulted in the last execution by hanging carried out in Arkansas. In 1914, Arthur Tillman of Delaware (Logan County) was convicted of murdering a young woman and sentenced to death by hanging. On July 14, 1914, he was hanged in the gallows on the site of the Paris jail. After that time, all executions conducted in Arkansas have taken place in the state prison.

For many years, one of the greatest threats to public health in Arkansas was tuberculosis, a contagious and often fatal disease. In 1910, the state established a tuberculosis treatment center near Booneville called the Arkansas State Tuberculosis Sanatorium, which developed into a world-renowned tuberculosis treatment center. At the height of its operations in the early 1940s, the sanatorium was a self-sufficient community with hospital facilities for 1,000 patients.

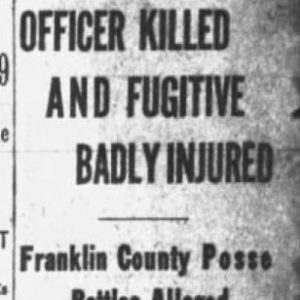

The incorrectly named “Logan County Draft War” took place mostly in Franklin County in 1918. The events were not tied directly to draft resistance during World War I but rather typical criminal behavior including burglary.

Hard times fell on the county in the Depression years of the 1930s. A decline in farm prices and a series of drought years devastated the farm economy. Unemployment became a major problem, and many families moved out of state to seek work.

World War II through the Modern Era

The country’s entrance into World War II in 1941 had a severe impact on Logan County. Young men were called into military service, and many families moved away to work in war-related industries. After the war ended in 1945, residents who had left the farms to go into military service or work in war industries remained in areas where good-paying jobs were plentiful. In 1950, the Korean War caused a further drain on the population when Arkansas National Guard units in the county were called to active duty. Returning veterans found it difficult to find employment in the county.

In the 1950s, economic conditions worsened. The coal mines in north Logan County closed. The sanatorium cut back its operations as its patient population dropped. Residents again moved out of the county to find jobs. Once flourishing rural communities such as Sugar Grove, Driggs, Barber, Prairie View, Midway, Blaine, Roseville, and Chismville began to fade.

Civic leaders realized that to prevent a further decline in population, changes had to be made in the economic base. Attracting small industries became a priority. These efforts paid off when small factories were established at Booneville, Paris, and Ratcliff, providing jobs for hundreds of workers producing such items as combs, shoes, and clothing.

By the 1960s, economic conditions had improved, and the population had increased slightly. But the next ten to fifteen years were challenging. Both railroads in the county ceased operations, and the tracks were removed. The tuberculosis sanatorium closed due to the emergence of new treatments for the disease. The county moved forward, however, to upgrade roads and public facilities.

In the late 1990s, the population of Logan County began to increase as retirees and young families moved into the county, attracted by the lifestyle of a rural area, the county’s natural beauty, and the proximity of outdoor recreation facilities. Job opportunities in small factories and public facilities had increased. Improved roads made it more feasible to reside in Logan County and commute to jobs in neighboring towns.

Attractions and Famous Residents

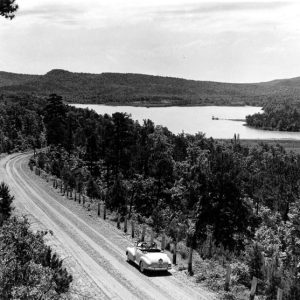

Logan County contains several attractions that are unique in Arkansas. Mount Magazine State Park, located on the highest elevation in Arkansas at 2,760 feet, features a handsome visitors’ center with informative exhibits on the flora and fauna of the mountain, a luxurious and spacious lodge, comfortable cabins, campgrounds, hiking trails, picnic areas, and facilities for hang gliding, rappelling, and nature study. Subiaco Abbey and Academy, a monastery and high school for boys established in the late 1800s in the town of Subiaco, combines an Old World charm with modern architecture. It offers tours and facilities for retreats. Cowie Wine Cellars at Carbon City, just outside of Paris, produced award-winning wines made from locally grown grapes and was home to the Arkansas Historic Wine Museum. Blue Mountain Lake in south Logan County and Lake Dardanelle on the Arkansas River in north Logan County are outstanding areas for camping, fishing and water sports. Other attractions include the Logan County Museum in Paris, the Evans Museum near Magazine. The county is home to many properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Paris Post Office and multiple sites around Cove Creek and Cove Lake (the latter including a bathhouse and a dam and bridge).

Several Logan County natives have achieved national prominence. Dizzy Dean, Paul Dean, Aaron Ward, and Floyd Spear became well-known major league baseball players during the 1930s. General John Paul McConnell served as chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force from 1965 to 1969. Elizabeth (Ward) Gracen, Miss America 1982, grew up in Booneville. Jim Bridges, a Paris native, achieved national acclaim as an actor and director in the film industry in the 1970s. Arkansas politician Jay Bradford and painter George Dombek are both associated with the county.

For additional information:

Logan County, Arkansas: Its History and Its People. Paris, AR: Logan County Historical Society, 1987.

Logan, Steve. “From Sarber to Logan.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 13 (Spring 1954): 90–97.

Titsworth, Elizabeth. Paris: One Hundred Years. Paris, AR: Paris Chamber of Commerce, 1989.

Wagon Wheels. Paris, AR: Logan County Historical Society (1980–).

Patricia L. Curry

Logan County Historical Society

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium

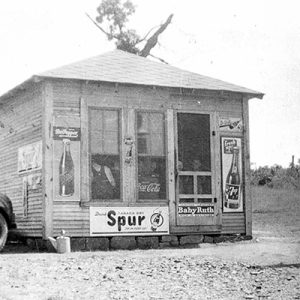

Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium  Barnett's Store

Barnett's Store  Booneville Bank

Booneville Bank  Booneville Courthouse

Booneville Courthouse  Booneville Street Scene

Booneville Street Scene  Boyd's Texaco

Boyd's Texaco  Cove Lake

Cove Lake  Cove Lake

Cove Lake  Cowie Wine Cellars

Cowie Wine Cellars  Driggs School

Driggs School  Logan County Apple Orchard, 1920s

Logan County Apple Orchard, 1920s  Logan County Courthouse in Paris

Logan County Courthouse in Paris  James Logan

James Logan  Logan County Courthouse

Logan County Courthouse  Logan County Courthouse, Southern District

Logan County Courthouse, Southern District  Logan County Draft War Article

Logan County Draft War Article  Logan County Fairgrounds

Logan County Fairgrounds  Logan County Map

Logan County Map  Logan County Veterans Memorial

Logan County Veterans Memorial  Magazine Street Scene

Magazine Street Scene  Mount Magazine State Park

Mount Magazine State Park  Shoal Creek School

Shoal Creek School  Annie Smith

Annie Smith  St. Scholastica Monastery

St. Scholastica Monastery  Subiaco Abbey

Subiaco Abbey  St. Benedict's Church at Subiaco

St. Benedict's Church at Subiaco  Sugar Grove

Sugar Grove

The Cherokee in Arkansas prior to the Trail of Tears were Chickamauga. There is documentation in government files showing the separation of the Cherokee Nation. They were referred to as the Upper Town and the Lower Town, a.k.a. Chickamauga, as proclaimed by President George Washington in his 4th annual address to the Continental Congress on November 6, 1792. Chickamauga arrived on the south side of the Arkansas River in the spring of 1809 (Arkansas Territorial papers). President Thomas Jefferson gave them (Thomas Jefferson Papers) that land south of the Arkansas River and the Treaty of 1828 giving that land away was never ratified by the U.S. Senate. The Chickamauga are still here today!