calsfoundation@cals.org

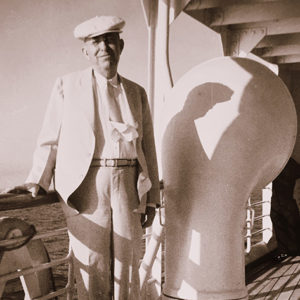

Justin Matthews Sr. (1875–1955)

Justin Matthews Sr. was a prominent Arkansas businessman, real estate developer, and community leader best known for his role in the development of the North Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Sherwood (Pulaski County) areas.

Justin Matthews was born on a farm near Monticello (Drew County) to Samuel James Matthews and Anna Wilson Matthews on December 23, 1875. The Matthewses were a very wealthy family in Drew County, as Samuel Matthews owned a law firm, a large nursery, and a fruit business. Samuel Matthews also served as Drew County judge and encouraged his son to study law, but Justin Matthews decided to pursue a career as a pharmacist.

Matthews married Mary Agnes Somers in 1901; they had three children. Around that time, Matthews sold the three drugstores he owned in the Monticello area, and the couple moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County). In 1902, Matthews founded the Rose City Cotton Oil Mill near the eastern edge of North Little Rock. A couple of years later, he invested the money made from his cottonseed oil business into real estate on both sides of the Arkansas River.

Within a short time of arriving in central Arkansas, Matthews was engaged in two controversial projects, one aimed at paving streets in North Little Rock and the other concerning the construction of two new bridges across the Arkansas River linking Little Rock and North Little Rock. According to his obituary, Matthews “circulated petitions in 1913 for the formation of two improvement districts to pave 152 blocks of North Little Rock streets, projects which had bitter opposition.” In addition, “when it was proposed in 1913 to build the present Main Street Bridge [across the Arkansas River], Mr. Matthews led a campaign to build the Broadway Bridge at the same time although many persons thought one bridge would be sufficient.” Both of these projects, financed publicly through improvement districts, were crucial to Matthews’s land development plans.

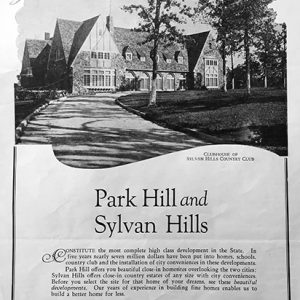

The early years of development in Park Hill—as Matthews christened the new residential area—were characterized by the construction of modest houses, usually bungalows or two-story, Craftsman-influenced residences. Aimed at first-time home buyers, houses in Park Hill were built as efficiently and inexpensively as possible by Matthews’s own company, first called the Matthews Land Company and later the Justin Matthews Company. Comparing his method of building houses to an automobile assembly line, Matthews announced in 1923: “We have launched into a home building campaign; we have built and equipped a complete wood work plant…[and] we are buying all materials in carload lots.” Although his plan called for Park Hill eventually to consist of 1,600 acres, the area was platted bit by bit as Matthews waited for several houses to be built in one section before opening another section for development.

In 1927, after six years of cautiously opening sections of Park Hill to a modest scale of development, Matthews apparently decided the time was ripe for a grander development that would compete for the upper-income residents who were buying homes almost exclusively in several recently opened “restricted” additions in Pulaski Heights (Pulaski County). The plat of Edgemont in Park Hill, officially blocks 101 through 107 of the Park Hill Addition, was recorded in 1927 with typical deed restrictions of the year, notably one pertaining to the size and cost of houses and one to the race of property owners, who were required to be “wholly of the Caucasian Race.”

During the same time, he began building homes in the area on the Ark-Mo Highway (now Highway 107) north of North Little Rock, an area he named Sylvan Hills. As part of his plans for this subdivision, Matthews began building the Sylvan Hills Country Club (now known as the Greens at North Hills) in 1926. In 1927, Matthews was appointed to the Arkansas State Highway Commission by Governor John Martineau.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression complicated the opening of Edgemont in Park Hill and Sylvan Hills. Only sixteen houses in Edgemont and a handful of homes in Sylvan Hills were built before construction was brought to a halt.

From 1931 to 1933, Matthews developed a park in the Lakewood subdivision, which he named T. R. Pugh Memorial Park in honor of Thomas R. Pugh of Portland (Ashley County), who was a close friend and benefactor of Matthews. Today, the park is more commonly known as “The Old Mill.” The park features a re-creation of an 1880s water-powered grist mill and other structures, which were designed and created by Mexican sculptor Dionicio Rodriguez.

Matthews died on March 21, 1955, at his residence on Cherry Hill in North Little Rock. He was survived by his second wife, Robin, his first wife having died in 1933. Matthews is buried in Little Rock’s historic Mount Holly Cemetery. An Arkansas Gazette editorial paid tribute to the man who, “on the high ground overlooking North Little Rock,” had “transformed a wilderness into a great community with homes, stores, schools, churches and service establishments.”

For additional information:

Adams, Walter M. North Little Rock, the Unique City: A History. Little Rock: August House, 1986.

Bradburn, Cary. On the Opposite Shore: The Making of North Little Rock. Marceline, MO: Walsworth Publishing Company, 2004.

Drew, Sara Ann. “A History of Argenta.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock 2010.

Duran, Ron, Cheryl Ferguson, Marvelle Harmon, Sarah Henson, Amy Sanders, and Becki Vassar. The Signs Still Say Sherwood: The Next 25 Years. Sherwood, AR: Arrow Printing, 2002.

Darrell W. Brown

Sherwood History and Heritage Committee

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Justin Matthews Sr.

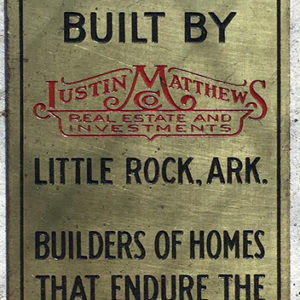

Justin Matthews Sr.  Justin Matthews Plaque

Justin Matthews Plaque  Justin Matthews Sr. Obituary

Justin Matthews Sr. Obituary  Sylvan Hills Country Club Ad

Sylvan Hills Country Club Ad

Justin Matthews’s parents are buried in Oakland Cemetery in Monticello. His mother’s parents are buried in the Old Monticello Cemetery in Monticello.