calsfoundation@cals.org

Poinsett County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Harrisburg |

| Established: | February 28, 1838 |

| Parent Counties: | Greene, St. Francis |

| Population: | 22,965 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 758.30 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

1,320 |

2,308 |

3,621 |

1,720 |

2,192 |

4,272 |

7,025 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

12,791 |

20,848 |

29,695 |

37,670 |

39,311 |

30,834 |

26,843 |

27,032 |

24,664 |

25,614 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24,583 |

22,965 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

19,391 |

84.4% |

| African American |

1,783 |

7.8% |

| American Indian |

102 |

0.4% |

| Asian |

61 |

0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

1 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

461 |

2.0% |

| Two or More Races |

1,166 |

5.1% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

829 |

3.6% |

| Population Density |

30.3 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$40,921 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$20,963 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

21.4% |

|

Poinsett County is located in Arkansas’s northeast corner. The St. Francis River travels north to south in the eastern portion of the county, and the L’Anguille River begins at the north boundary and runs south through the center of the county. Crowley’s Ridge, a highland anomaly that begins in southeast Missouri and terminates near Helena (Phillips County), runs through the center of the county. On the eastern side of the ridge is the rich, alluvial land of the Delta, which primarily hosts cotton farming, while on the western side is prairie land used mostly for the cultivation of rice.

European Exploration and Settlement

When the first permanent settlers arrived in what was to become Poinsett County, a few communities of Native Americans were there. Wild game and buffalo roamed throughout the county. The land lying east of Crowley’s Ridge was generally flat, overflow ground during much of the year, the natural drainage being poor. Some of the land lying west of the ridge was prairie with large tracts of open land that provided excellent grazing for the few buffalo in Poinsett County. All of the land west of Crowley’s Ridge was flat and mostly timbered. During the territorial period, many settlements of Cherokee were established in the region, as well as a small settlement of Shawnee and another of Delaware; all these groups had moved west of the Mississippi before the Louisiana Purchase. All of these settlements were farms with permanent dwellings, cornfields, and other improvements. The New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812 changed the landscape of Poinsett County, prompting these Indian communities to relocate south and west of the region.

Louisiana Purchase through Reconstruction

The first permanent white settlers in Poinsett County were Charles and Rebekah Shaver. In the fall of 1824, they left Missouri and crossed into Arkansas at a place called Chalk Bluff in what is now Clay County. The Shaver family is said to have followed an old Indian trail down Crowley’s Ridge with two wagons, although a federal mail post road had been built by 1815, linking east Arkansas to St. Genevieve and St. Louis. They found a trapper living in a small cabin on Sugar Creek (now called Bay Village). Shaver bought the trapper’s place and settled his wife, two sons, daughter, son-in-law, and several slaves there.

Poinsett County was established on February 28, 1838. It was named for Joel Roberts Poinsett, a statesman, scientist, and botanist. Poinsett was the secretary of war in President Van Buren’s administration. He was also a horticulturist of note and is remembered foremost for his introduction of a new flower, the poinsettia, into the United States. Poinsett never visited Poinsett County.

Although there were a few communities of widely scattered settlers, there were no towns in the area when Poinsett County was created. When Governor James S. Conway signed the act creating Poinsett County, William Harris was named the first county judge. The first terms of the county court and other county business was conducted at his home until a permanent seat could be selected. A site for the new county seat was selected about four miles north of Judge Harris’s home. It was named Bolivar after General Simon Bolivar, a South American revolutionary hero. Joel R. Poinsett, whose name the county bears, had interested himself in Simon Bolivar. Two buildings were built—a courthouse and jail. The first term of court was held in the new courthouse in September 1839. Bolivar was a typical frontier town with a smattering of general stores, blacksmith shops, hotels, law and doctors’ offices, and saloons. Bolivar also boasted one of the best horse-racing tracks in this part of the country. Goods often had to be shipped from New Orleans, Louisiana, up the Mississippi River to Memphis, Tennessee. They were then taken by riverboat, by way of the St. Francis River, to Wittsburg (Cross County) and by wagon up Crowley’s Ridge to Bolivar. Wittsburg, located in what is now Cross County on the east edge of Crowley’s Ridge, was where the St. Francis River met Crowley’s Ridge, providing a natural place to establish a river port. Wittsburg eventually became an important trading port for all of eastern Arkansas that bordered the ridge, though now it no longer exists.

Early settlers had trouble keeping their livestock because there were no fences, and the livestock were allowed to roam free. In the winter months, the horses and cattle ranged far from home. In the spring, settlers tried to round up the strayed livestock, many of which were never found or were found drowned in the lowlands on either side of the ridge.

In 1856, the county seat was moved to a new city named Harrisburg, named after Benjamin Harris, who was the son of the first county judge and who gave the land on which the new courthouse was built; there had been much agitation for moving the seat of the county government to the center of the county, and a hotly contested election resulted in the decision to move the seat south to Harrisburg. Poinsett County was much larger than it is today. The county’s size has been reduced twice since its creation. In 1858, Craighead County was created, taking much of the north part of the county. In 1862, the Confederate legislature created Cross County, which consumed much of the southern portion of the county. Some land was added, however, to the county to the east. The area where the cities of Marked Tree, Lepanto, and Tyronza are located was not part of Poinsett County until the creation of Craighead County in 1859 and the creation of Cross County in 1862. The eastern boundary of Poinsett County was established in two stages when these two counties were established. During the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812, a large tract of land in the eastern portion of the county sunk beneath the level surface and became known as “the sunken lands.” The New Madrid Fault runs from the Marked Tree area to the northeast.

Settlers slowly came to the county, some coming down the ridge from Chalk Bluff on the Missouri border, some coming up the St. Francis River to Wittsburg and then up Crowley’s Ridge, and some even coming overland from east of the Mississippi River. The Poinsett County delegation voted not to secede from the Union when the first convention was held in Little Rock (Pulaski County) to decide the issue. As was the case for many counties in Arkansas, the Civil War devastated what little commerce there was in Poinsett County.

The white population of the county in 1860 was 2,535 with another 1,086 enslaved. The economy of the county was closely tied to the institution of slavery, with landowners relying on slave labor to harvest row crops. The 1870 federal census recorded the county population at just 1,721. Part of this population loss can be attributed to the creation of Cross County in 1862. The politicians who took over the county government after the Civil War almost bankrupted the county.

Post-Reconstruction through Early Twentieth Century

The coming of the railroads in the early 1880s drastically affected the economy of Poinsett County. The growth of the county had been stalled by the inability to get products to market. The county contained vast natural resources but had no practical way to market them. The only river that was used for commerce was the St. Francis, located in the eastern part of the county. Some people opposed the railroad, especially hunters who thought the trains scared the animals, but they were unsuccessful in their opposition. In 1881, the Texas and St. Louis Railway Company began laying the county’s first track through the towns of Weiner and Fisher. The track, a narrow gauge, was finished the next year. In 1882, the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railway (Union Pacific) came through the center of the county and serviced Whitehall, Harrisburg, and Greenfield. In 1883, the Kansas City, Ft. Scott, and Gulf Railway (Burlington Northern) came through Tyronza and Marked Tree on the east side of the county. The cities along the tracks grew rapidly. More sawmills came to the county, and the harvest of the vast timberland began in earnest. The timber industry expanded rapidly because the timber could now be more easily moved to market. The railroads connected the wilderness of Poinsett County to the large industrial centers. The trains took thousands of furs out of the county, shipped cattle to market in St. Louis, Missouri, and carried cotton and lumber to the mills.

Poinsett County was harder hit during the Flood of 1927 than any other Arkansas county. Though residents were able to relocate their livestock to the high ground of Crowley’s Ridge, over 200,000 acres were under water at the worst phase of the flooding, and thousands of sharecroppers and their families were rendered homeless. Many historians believe that this flood and its impact upon poor sharecroppers played a role in the creation of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU), one of the few interracial unions in its day, which was founded in Tyronza. Established to advocate for the rights of sharecroppers and tenant farmers to earn a reasonable living, in contrast to the abuse and poor payment they often received from plantation owners, the STFU was one of the few interracial unions in its day. Founded by Harry Leland Mitchell and Clay East, the organization also had female members at all levels.

The last recorded lynching in Arkansas occurred in Poinsett County on April 29, 1936, when Willie Kees, a black man who had been accused of rape, was taken from police custody in Lepanto and killed by a group of masked men. It was the only recorded lynching to occur in the county.

World War II through the Faubus Era

During World War II, many Germans were captured in North Africa and sent to German prisoner-of-war camps in the United States. Poinsett County housed two of these camps, one in Marked Tree and one in Harrisburg. The German prisoners assisted in manual labor and were especially helpful to the farmers, who had first call on their services because of the national need for food and fiber—rice and cotton—during the war. The prisoners were returned to their homeland after the war. There are no memorials of this time in the area.

Poinsett County native James Richard Hendrix received the Medal of Honor for his actions during World War II.

Like much of eastern Arkansas, the population of rural Poinsett County began to shrink with the mechanization of agriculture. Small schools and small rural churches found it more and more difficult to survive. The small rural schools were consolidated into the larger town schools, especially in 1948. Many sharecropper homes were destroyed and the land planted to crops.

Local farmer David Cox ran against Governor Orval Faubus in 1962, gaining some publicity for his campaigning style and moral opposition to Faubus’s stance on the desegregation of Central High School.

Modern Era

Modern-day Poinsett County is mainly rural, with farming being the principal industry. It is one of the highest producers of rice in the nation and also grows much cotton and soybeans. Although Arkansas County is known as the hub of rice production in Arkansas, Poinsett County has the most acreage devoted to rice production than any county in the state. Most manufacturing facilities (including footwear and apparel factories) in the county closed over the last decades of the twentieth century and early years of the twenty-first century.

Incorporated cities and towns in the county are: Harrisburg, Marked Tree, Trumann, Lepanto, Tyronza, Weiner, Fisher, and Waldenburg.

Numerous county residents were active musicians in a variety of genres. Gene Darrell “Bud” Deckelman played country and rockabilly music, while his cousin Joseph Dewitt “Sonny” Deckelman also played rockabilly and owned a record label. Vaden Records in Trumann produced albums of gospel, blues, and early rock and roll music.

A number of structures in Poinsett County are on the National Register of Historic Places, including the county courthouse, the Tyronza Water Tower, the Marked Tree Lock and Siphons, and the Rivervale Inverted Siphons.

Various festivals and events are held in the county on a regular basis. These include the Lepanto Terrapin Derby, the Arkansas Rice Festival, and the Trumann Wild Duck Festival. Lake Poinsett State Park and the Southern Tenant Farmers Museum are located in the county.

For additional information:

Hartness, Richard L. Wittsburg, Arkansas: Crowley’s Ridge Steamboat Riverport, 1848–1890. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1978.

Poinsett County, Arkansas: History and Families. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 1998.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth-Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996.

Williams, Harry Lee. The History of Craighead County. Little Rock: Parke-Harper, 1930.

Clyde Ford

Poinsett County Historical Society

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Chopping Cotton

Chopping Cotton  Harrisburg School Children

Harrisburg School Children  Harrisburg Street Scene

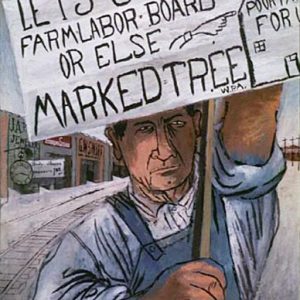

Harrisburg Street Scene  Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn

Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn  Marked Tree Street Scene

Marked Tree Street Scene  Perry Ouzts

Perry Ouzts  Painted House Museum

Painted House Museum  Poinsett County Courthouse

Poinsett County Courthouse  Poinsett County Courthouse

Poinsett County Courthouse  Poinsett County Map

Poinsett County Map  Joel Poinsett

Joel Poinsett  Rice Harvesting

Rice Harvesting  Singer Forest Natural Area

Singer Forest Natural Area  Southern Tenant Farmers Museum

Southern Tenant Farmers Museum

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.