calsfoundation@cals.org

St. Francis County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Forrest City |

| Established: | October 13, 1827 |

| Parent County: | Phillips |

| Population: | 23,090 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 634.78 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

1,505 |

2,499 |

4,479 |

8,672 |

6,714 |

8,389 |

13,543 |

17,157 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

22,548 |

28,385 |

33,394 |

36,043 |

36,841 |

33,303 |

30,799 |

30,858 |

28,497 |

29,329 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

28,258 |

23,090 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

9,551 |

41.4% |

| African American |

12,561 |

54.4% |

| American Indian |

65 |

0.3% |

| Asian |

127 |

0.6% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

8 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

189 |

0.8% |

| Two or More Races |

589 |

2.6% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

686 |

3.0% |

| Population Density |

36.4 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$35,348 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$18,447 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

24.9% |

|

St. Francis County in eastern Arkansas is divided north-south by Crowley’s Ridge, which forms the high ground upon which the county seat, Forrest City, was founded. The St. Francis and L’Anguille rivers further subdivide the county and provide the resources for the agricultural industries that have long been central to the county’s economy.

Pre-European Exploration

Ample evidence of prehistoric habitation of St. Francis County exists, including head pots. Clarence Bloomfield Moore conducted extensive excavations along the St. Francis River, including two Indian mound sites in St. Francis County, and later archaeologists have returned to some of these sites for further investigation.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The first permanent white settlers, along with their slaves, arrived in St. Francis County from Tennessee and Kentucky, settling along the high ground of Crowley’s Ridge. Noteworthy settlers include Samuel Fillingen and John Johnson, the latter of whom was a representative in the territorial legislature. A few scattered Cherokee campsites were located in the vicinity of what is now Village Creek State Park. Once completed, the Military Road from Memphis, Tennessee, to Little Rock (Pulaski County), which crossed near the northern border of St. Francis County, brought additional settlers from the east. Travelers on the road crossed Blackfish Lake on a ferry that operated for about a decade.

On October 13, 1827, the territorial legislature carved St. Francis County, named after the river that runs through it, from land in Phillips County. A temporary county seat was set up at the home of William Strong until a permanent one was established at Franklin. However, in 1840, the county seat was moved to Madison. In 1855, the seat was moved again to Mount Vernon, but the courthouse burned the following year, and Madison again regained its role.

By 1860, there were 8,672 residents in the county, with enslaved people constituting roughly thirty percent of the total population. Cotton and corn were the mainstays of the county’s economy at the time. Both of the representatives from the county at the 1861 Secession Convention were part of slave-owning families, with one of the representatives, James Shelton, owning at least twenty enslaved people.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Five companies of soldiers were raised for the Confederacy in St. Francis County, which was the site of several minor military incidents during the Civil War. St. Francis County resident Brigadier General Lucius Walker recruited troops in the area. The August 3, 1862, Skirmish at L’Anguille Ferry was a Confederate victory that limited the activities of Union troops in eastern Arkansas until the following year. On March 5–12, 1863, Colonel Powell Clayton led an expedition from Helena (Phillips County) up the St. Francis and Little rivers. After surprising a Confederate force of about seventy-five at Madison, he continued north, capturing prisoners and acquiring supplies along the way. His expedition encountered another Confederate force at Madison on its return trip south, but it was able to return to Helena safely. The Confederates, however, scored another victory during the May 12, 1863, Skirmish at Taylor’s Creek. During a February 13–14, 1864, expedition on the St. Francis River on the steamboat Hamilton Bell, Captain Charles O’Connell of the Fifteenth Illinois Cavalry personally captured Colonel John E. Josey of the Fifteenth Arkansas Infantry Regiment. A skirmish at Madison late in the war erupted during a scout by Union troops stationed at Helena.

In 1862, to prevent government records from falling into Union hands, they were moved from the courthouse at Madison to a location in the nearby woods. However, the woods caught fire, and the records were destroyed. During Reconstruction, cholera broke out among occupying Federal troops stationed at Madison, leading them to set up camp near Mount Vernon.

Before the war, the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad was finished only from Memphis to Madison and from Little Rock to DeValls Bluff (Prairie County). The war put a stop to this construction. Immediately following the war, however, Nathan Bedford Forrest, Confederate general and later a major figure in the establishment of the Ku Klux Klan, who was familiar with the area, secured a contract from the railroad company to cut across the ridge, beginning work in 1866 with almost 1,000 Irish laborers under his command. The site of his commissary became the town of Forrest City, which was first platted on March 1, 1869. In 1874, the county seat was moved to Forrest City after a vote on the matter; the citizens of Madison, however, refused to part with county records, thus leading some citizens of Forrest City to go there one evening and steal the safe containing the records. However, the frame building that served as a courthouse at Forrest City was burned a few months later in an attempt to destroy records revealing certain criminal acts.

The Forrest City Times newspaper was established in 1871 and remains the oldest continually published newspaper in the county; it was later renamed the Times-Herald.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

In the fall of 1879, yellow fever struck Forrest City. By October 20, thirteen people had died. The entire town was quarantined, however, and the fever did not spread.

Black migration into the area soon threatened those who held fast to white supremacy. By 1880, African Americans constituted forty-one percent of the total population, but that increased to fifty-nine percent by the next census. In 1888, Black Republicans “fused” with white Union Labor Party candidates, capturing important county offices from the Democrats. Local whites were irate at the election of three Black candidates to office.

School board elections the following year proved the next bone of contention between Black and white voters, and, in May 1889, what newspapers called the “Forrest City Riot” took place, claiming the lives of four and drawing condemnation upon Arkansas from national newspapers. At the center of this event was Americus M. Neely, a local Black Republican politician and editor of the Advocate, Forrest City’s Black newspaper. During the May 18, 1889, school board election, Neely reportedly got into a fight with a white man in the vicinity of the polls and was knocked down. He approached the former sheriff, Captain John Parham, for protection, but Marshal F. M. Folbre “interfered and commanded the peace,” according to the Arkansas Gazette. Parham’s son, Thomas, heard the disturbance and, seeing his father and the marshal engaged in heated conversation, shot the marshal in the back of the head. Before dying, Folbre shot Thomas Parham dead. Sheriff D. M. Wilson, who had “sided with the mixed element, mostly colored, in all political matters,” arrived on the scene but was subsequently shot and killed by an unknown assailant. Despite the fact that two of the men died at each other’s hands and that no evidence linked Neely with the death of the sheriff, armed mobs raged through the town in search of Neely. They found him the following morning hidden under the floorboards of the Advocate building and riddled him with bullets. Officials also arrested Neely’s father and brother. Armed men arrived from nearby communities to help Forrest City fend off an imagined attack from Black outlaws, while Governor James P. Eagle made a special appearance to reassure the town’s white citizens. The Black county coroner and school board candidate were ordered to leave town. The Philadelphia Press and the Chicago Tribune both condemned the actions of Forrest City’s white citizenry, the latter writing that “the work of killing off Republicans goes merrily on in Arkansas.” As a result of the violence, the school board election saw local Democrats victorious, and several Black officials were driven from town.

Numerous other incidents of racial violence took place in the county during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An African American man known as Brooks was killed in 1894 after allegedly asking to marry the daughter of his white boss. Nathan Lacey lost his life at the hands of a mob in 1911 after allegedly attacking the wife of his boss. Four years later, William Patrick faced two juries that split on charges that he allegedly killed a white landowner. A mob seized him from the local jail before a third trial could commence and hanged Patrick. In the late 1920s, the prosecutions of Robert Bell and Grady Swain, two African American teens, for murder, and the appeals that followed, cast light upon the impunity of local law enforcement in their dealings with Black defendants, including allegations of torture used against the boys.

In 1897, a new county courthouse was constructed at a cost of $26,700.

Early Twentieth Century

The Flood of 1927 inundated the county—water covered the eastern half, and the L’Anguille River in the western half backed up and poured out on the surrounding land. Only the high ground along Crowley’s Ridge remained truly safe. The Red Cross staffed three relief camps in the county at Forrest City, Bruins Creek, and Hughes, the last of which alone held about 4,000 refugees from the area. Forrest City’s camp was the largest in the state, housing 15,000 people made homeless by the flood. A tornado hit the town of Wheatley in 1929, killing five. The county also suffered during the Drought of 1930–1931, with half the farm population receiving relief aid from the Red Cross.

On September 4, 1933, the St. Francis River Bridge opened east of Forrest City. The bridge, which is part of Highway 70, brought increasing numbers of motorists through the city. The bridge is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The county was the site of a plane crash on January 14, 1936, leading to the deaths of all on board. The namesake of the Dyess Colony, William Reynolds Dyess, was among those killed.

Christ Church Parochial and Industrial School operated in the county from 1923 until 1968. Serving the African American community, the private school was supported by the Episcopal Church.

World War II through the Modern Era

Beginning in 1944, the town of Hughes was home to a prisoner-of-war work camp housing about 250 Germans. The prisoners conducted agricultural work in the absence of farm laborers then serving in the military.

St. Francis County is along one of the main transportation arteries through Arkansas, and the construction of Interstate 40 in the 1960s paralleled previous transportation initiatives, such as the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad and Highway 70. However, the only county town touched by the modern interstate highway is Forrest City; it skirts all other communities.

Forrest City was one of three Delta towns chosen by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) for a local headquarters to promote civil rights activism in the 1960s. Local officials had adopted a “freedom of choice” plan that resulted in de facto segregation, and Black schools were inadequate and infested with vermin. In September 1965, ninety percent of the Black student body participated in a boycott to protest local conditions. Police arrested approximately 200 protestors. Four years later, racial tensions again flared up when the all-white school board fired a Black teacher active in the civil rights movement, leading to an organized boycott of white-owned stores and a protest march to Little Rock.

St. Francis County in the modern era suffers many of the same problems as other counties in the Arkansas Delta, though it has not decreased in population as dramatically as Lee or Phillips counties to the south, for example. The 2010 federal census recorded a poverty rate of almost thirty-two percent. The county is home to nine incorporated communities, but aside from Forrest City—which is home to more than half the people in the county—only Hughes has a population surpassing 1,000 as of the 2020 Census, indicating a countryside largely depopulated. Other communities in the county include Palestine, Caldwell, Colt, and Widener.

Agriculture remains the mainstay of the economy. East Arkansas Community College, which opened for classes in 1974, began conducting a number of job training courses for the community, and a number of non-profit organizations started work to revitalize the area’s economy. Crowley’s Ridge Technical Institute operated in Forrest City from 1967 until 2017 when it merged with East Arkansas Community College.

Famous Residents

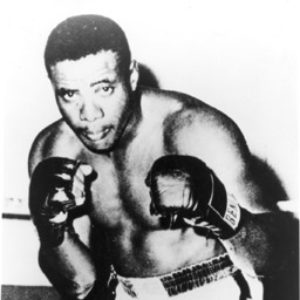

Mark W. Izard settled in St. Francis County in 1825 and served in the state legislature and as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1836. In 1855, he was appointed as the second territorial governor of the Nebraska Territory. The first African American to run for governor of Arkansas, Josiah Homer Blount, resided in both Forrest City and Madison. Boxer Sonny Liston was born in St. Francis County, as was singer and songwriter Charlie Rich. Rhythm and blues and gospel singer Al Green was born in Forrest City. Scott Bond of Madison was born into slavery but rose to become one of the richest people in the state during his time. Well-known major league baseball player Don Kessinger was born in Forrest City.

Attractions

The St. Francis County Museum is housed in the Rush-Gates Home, built in 1906. Village Creek State Park straddles the border with Cross County to the north. The L’Anguille and St. Francis rivers attract boaters and fishermen. The Crowley’s Ridge Parkway, a National Scenic Byway, runs through the county. St. Francis County has several places listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including some noteworthy homes. Sites listed on the National Register include the Hughes Water Tower, the Blackfish Lake Ferry Crossing, and the burial plot for the Scott Bond family.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Eastern Arkansas: Arkansas, Crittenden, Cross, Lee, Monroe, Phillips, Prairie, St. Francis, White, and Woodruff Counties. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1890.

Chowning, Robert W. History of St. Francis County, Arkansas, 1954: A Narrative Historical Edition Preserving the Record of the Growth and Development of St. Francis County, Arkansas, and Chronicling the Genealogical and Memorial Records of its Prominent Families and Personages. Forrest City, AR: Times-Herald Publishing Company, 1954.

Deaderick, Michael R. “Racial Conflict in Forrest City: The Trial and Triumph of Moderation in an Arkansas Delta Town.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Spring 2010): 1–27.

Finley, Randy. “Crossing the White Line: SNCC in Three Delta Towns, 1963–1967.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Summer 2006): 117–137.

Kirk, John A., Kathleen Burrell, Brittany Fugate, Christy Hendricks, Ellis Eugene Thompson, Michael White, Logan H. Yancey. “Criminal Justice in the Age of Segregation: The Arkansas Cases of Robert Bell and Grady Swain.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Spring 2022): 19–45.

Welch, Melanie K. “Violence and the Decline of Black Politics in St. Francis County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Winter 2001): 360–393.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Allison, Luther

Allison, Luther Blackfish Lake Ferry Site

Blackfish Lake Ferry Site Caldwell (St. Francis County)

Caldwell (St. Francis County) Colt (St. Francis County)

Colt (St. Francis County) Madison, Skirmish at

Madison, Skirmish at Palestine (St. Francis County)

Palestine (St. Francis County) Patrick, William (Lynching of)

Patrick, William (Lynching of) Widener (St. Francis County)

Widener (St. Francis County) Avery Hotel

Avery Hotel  Scott Bond's House

Scott Bond's House  Scott Bond

Scott Bond  Carl's Cafe

Carl's Cafe  East Arkansas Community College

East Arkansas Community College  East Arkansas Community College

East Arkansas Community College  Forrest City Refugee Camp

Forrest City Refugee Camp  Entering Goodwin

Entering Goodwin  Hughes Flood

Hughes Flood  Sonny Liston

Sonny Liston  Lucerne Gin

Lucerne Gin  "Luther's Blues," Performed by Luther Allison

"Luther's Blues," Performed by Luther Allison  Mastodon Femur

Mastodon Femur  "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World," Performed by Charlie Rich

"The Most Beautiful Girl in the World," Performed by Charlie Rich  St. Francis County Museum

St. Francis County Museum  St. Francis County Courthouse

St. Francis County Courthouse  St. Francis County Map

St. Francis County Map

Strong’s was never even a county seat. He was the postmaster at St. Francis with the post office and eight buildings already built with shops and a horse-racing arena with lots for sale in the 1832 Arkansas Gazette and was the Phillips territorial seat and the St. Francis County seat until it was moved to Mount Vernon.