calsfoundation@cals.org

Stone County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Mountain View |

| Established: | April 17, 1873 |

| Parent Counties: | Independence, Izard, Searcy, Van Buren |

| Population: | 12,359 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 606.44 square miles (2020 Census) |

|

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: |

|||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

5,089 |

7,043 |

8,100 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

8,946 |

8,779 |

7,993 |

8,603 |

7,662 |

6,294 |

6,838 |

9,022 |

9,775 |

11,499 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12,394 |

12,359 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

11,488 |

93.0% |

| African American |

21 |

0.2% |

| American Indian |

103 |

0.8% |

| Asian |

30 |

0.2% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

2 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

88 |

0.7% |

| Two or More Races |

627 |

5.1% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

271 |

2.2% |

| Population Density |

20.4 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$38,188 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$20,695 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

19.8% |

|

Stone County, named for its numerous rocky ridges and rocky soil, is widely known for its preservation of the folk music and traditions of the Ozark Mountains. Rivers, streams, and forests provide rich natural habitats for wildlife in the diverse landscape from river bottom to hilltop.

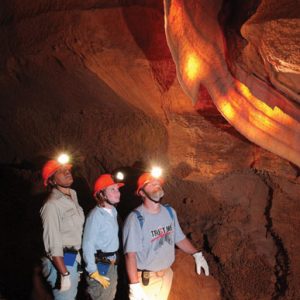

The White River forms the county’s northeastern border. Many spring-fed creeks, including the South Sylamore, are tributaries. A familiar tributary of the North Sylamore is Blanchard Springs. Known for cool, clear water that is a haven for trout and bass, the White River provides recreational opportunities in fishing and canoeing and is the source for the county’s public water system. Hell Creek Cave, near the White, is home to the endangered Cambarus zophonastes, a blind crayfish. This is the only known population in the state. The Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission owns the cave.

The 131,000-acre Ozark National Forest, Sylamore District, encompasses the northern portion of the county, providing recreational opportunities such as swimming, hiking, camping, biking, and hunting, including the Syllamo Mountain Bike Trail and the Sylamore Shooting Range. Within the national forest is Blanchard Springs Caverns, a living cave administered by the U.S. Forest Service.

Ozark Folk Center State Park preserves traditional Ozark crafts and music through living-history demonstrations. Musical programs are held in the folk center’s main auditorium. A collection of folk music, stories, and other documents is maintained at the Ozark Cultural Resource Center on the grounds.

Although one of the state’s younger counties, Stone County is home to numerous listings on the National Register of Historic Places. Among these is the Sylamore Creek Bridge, known locally as the Swinging Bridge, one of only two surviving wire-cable suspension bridges in the state. Other listings include the Alco School and the Mountain View Waterworks. The Stone County Special School District No. 30 is on the Arkansas Register of Historic Places.

Pre-European Exploration through Early Statehood

Prior to the white settlement, Native Americans inhabited what is now Stone County. Their presence for many centuries is apparent through the artifacts found near springs, creeks, and along the river. At least two prehistoric pictographs are located in the county, the Pictograph Cave and the Fox Pictograph. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Stone County was part of the hunting grounds of the Osage, who lived farther north; treaties ceded the land to the United States government, and the Osage moved west out of Arkansas. Twentieth century accounts of a Creek chief named Syllamo, for whom the Sylamore Creek was named, appear to have no supporting evidence.

White settlers were living in the area by 1830. Some of the early families were Hess, Ivy, Partee, Lancaster, Whitfield, Overton, Pittman, Riggs, Livingston, Creswell, Brown, and Young. Many early settlers came from Tennessee. Like many others, they were continuing the move west. Some of the early settlers received land grants for their service in the War of 1812.

Civil War through Reconstruction

During the Civil War, many men from what is now Stone County left their homes to join the war effort. There was little Civil War action in the county, but a few Confederate units were in the area and continued hit-and-run attacks on Union troops throughout the war. In 1862, the Peace Society was organized at Sylamore and was made up of seventy-six to eighty men from the area of Searcy and Izard counties, which includes present-day Stone County. The men did not want to become involved in the war for either side but were eventually chained and sent to Little Rock (Pulaski County) to the Confederate authorities and given the option of joining the Confederate cause or being shot. All but two joined the Confederacy.

Some munitions production took place in what is now Stone County, centered along Sylamore Creek. Confederate forces protected these facilities from the encroachment of Union forces after the Battle of Pea Ridge. This led to an engagement on June 19, 1862, at Knight’s Cove. In January 1864, a few skirmishes took place along the Sylamore Creek as the Union army searched for Confederate Colonel Thomas R. Freeman and his troops and met with resistance. Despite the search efforts, Freeman remained elusive.

Action was also reported near Buckhorn (present-day St. James) on May 25, 1864. Confederate General Jo Shelby and his men were marching from Clarksville (Johnson County) to Batesville (Independence County). In what is now Stone County, they marched through Richwoods and on to Buckhorn, where they met up with a group of “mountain boomers” under the command of Bill Williams. The men were Union and Confederate deserters and bushwhackers. General Shelby’s account states that forty-seven were killed and two captured by the Confederacy before continuing on toward Batesville.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The legislature created Stone County on April 21, 1873, as the seventy-third county from parts of Independence, Izard, Searcy, and Van Buren counties. One reason for the creation of the new county was the natural barrier of the White River, which made it difficult for residents to reach the county seat. Local businessman Elijah Chappell named Mountain View the county seat. He had submitted the name, which subsequently was drawn out of a hat full of contenders. Mountain View was incorporated in 1890.

The first federal census to include Stone County, in 1880, reported a population of more than 5,000, with ninety-nine of those in Mountain View. The county courthouse, still in use, was built in 1922, replacing a wooden structure constructed in 1888. The two-story building is made of large hand-cut stone. The wall surrounding the structure that creates the court square was built with stones from all four corners of the county. Stone County’s population continued to increase as the county seat grew. Local businesses grew in number, and stone buildings replaced wooden structures. Although the owners and types of businesses have changed over the years, the unique look of the square still exists. A general merchandise store has remained with the family that established it in 1898. It began as G. D. Lancaster General Merchandise and continues to operate as C. K. Lancaster & Son. The courthouse was the site of the 1929 trial of multiple defendants for the alleged murder of Connie Franklin.

In the county’s early days, the economy was based on small acreage cash crops such as grain and cotton along with timber, trapping, and livestock.

In 1898, an African-American boy (unnamed in reports at the time) was lynched over a suspected burglary after being suspected of stealing from his emplyer.

World War II through the Faubus Era

The residents of Stone County, like the rest of the country, suffered from the effects of the Great Depression. The self-sustaining lifestyle they were used to in this isolated area helped them survive. Due to very poor road conditions, livestock, timber, and other goods were shipped by rail or by water. People survived by growing their own food, trapping, harvesting herbs, making corn whiskey, and bartering with those who had what they needed.

During World War II, like other areas, Stone County was affected by rationing. Women began to work outside the home, and people collected items, such as scrap rubber, to help with the war effort. Stone County citizens worked to help with the war effort by increasing farm production in milk products, eggs, Irish potatoes, and peanuts. At the close of the war, soldiers returned home, and life resumed. In 1947, a fire in the business district of Mountain View destroyed thirteen businesses and damaged four others, providing another setback for the development of the county. An effort to create a television show set in Stone County led to the creation of a pilot titled The Amazing Adventures of My Dog Sheppy. The pilot was not successful and the show was never aired.

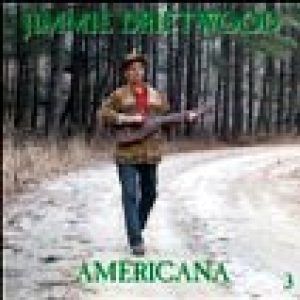

In 1963, several pieces began to fall into place that would bring Stone County out of its disadvantaged state and turn its county seat into the “Folk Music Capital of the World.” In April, the first annual Arkansas Folk Festival was held, featuring crafts and local folk music. Those responsible for the first festival were the Stone County Development Council, County Extension Agency, the local Tourist and Recreation Group, Jimmy Driftwood (who sponsored the music show portion of the festival), and the Ozark Foothills Handicraft Guild. The Rackensack Folklore Society, a group dedicated to preserving traditional folk music in the area, formed in 1963. From the recognition of these local talents came a plan to boost the county’s economic development. A group of businessmen and musicians went to Washington DC to lobby for grant money to showcase the county’s heritage by building a music auditorium, and to build a water and sewer system. Stone County musicians, including nationally known musician and songwriter Driftwood, performed on the steps of the U.S. Capitol. Although this trip was unsuccessful, funding for the folk center was obtained in 1968 with the help of U.S. Representative Wilbur D. Mills of Arkansas.

A center of folklife and culture, the county attracts numerous artists and musicians. Sculptor Joseph Bruhin, musician Ollie Eva Woody Gilbert, and folklorist W. K. McNeil all resided in the county.

Modern Era

Before 1973, two industries made their home in the county: Ozark Woodworking, which opened in the mid-forties, and Blanchard Shirt Corporation, which opened in the late sixties and provided many women their first work outside the home. The Ozark Folk Cultural Center and Blanchard Springs Caverns opened in 1973. The center opened for the annual Arkansas Folk Festival in April; it opened officially in May. The caverns opened during the summer. The opening of the state and national parks helped bring the economic boost the county had hoped for, along with a new industry: tourism. When the folk center opened, local craftspeople and musicians began receiving income for their work, which consisted of everyday tasks such as making lye soap and shoeing horses. The county’s core industries of timber, livestock, and poultry continue to contribute to the economy, and several new industries have been established. Conestoga Wood Specialties opened in 1988, making solid wood drawer fronts and doors for cabinets. It became the largest company in the county, with about 250 workers.

Communities in the county include Mozart, Onia, Turkey Creek, Pleasant Grove, Rushing, Marcella, Optimus, Alco, Big Springs, Herpel, Chalybeate Springs, Kahoka, Arlberg, and Hedges.

Education

Education in Stone County began in Mountain View in the late 1800s with the first subscription school. In 1894, the Stone County Academy opened its doors. The academy was replaced in 1928 when the Mountain View Special School District No. 30 building was built. At one time, there were seventy-one school districts in Stone County. In the 1940s, most of these one-room schools consolidated with the five major schools: Fifty-Six, Mountain View, Pleasant Grove, Rural Special near Fox, and Timbo. Pleasant Grove lost its high school to fire in 1965, beginning its consolidation with Mountain View. In 1974, its elementary students were bused to Mountain View as well. Fifty-Six eventually became part of the Tri-County School, which closed its doors in 1993. In 2005, both Rural Special and Timbo consolidated with Mountain View. Presently, each school maintains its own campus as part of the Mountain View School District. College level–education came to Stone County in the fall of 1997 with the opening of an Ozarka College campus in Mountain View.

For additional information:

Heritage of Stone. Mountain View, AR: Stone County Historical Society (1972–).

Home for the 100th: A Pictorial History of Mountain View, Arkansas. Marceline, MO: Heritage House, 1991.

Stephanie Lawrence Labert

Mountain View, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Alco (Stone County)

Alco (Stone County) Amazing Adventures of My Dog Sheppy, The

Amazing Adventures of My Dog Sheppy, The Arlberg (Stone County)

Arlberg (Stone County) Big Springs (Stone County)

Big Springs (Stone County) Buck Horn, Skirmish at

Buck Horn, Skirmish at Chalybeate Springs (Stone County)

Chalybeate Springs (Stone County) Hedges (Stone County)

Hedges (Stone County) Herpel (Stone County)

Herpel (Stone County) Kahoka (Stone County)

Kahoka (Stone County) Marcella (Stone County)

Marcella (Stone County) Mozart (Stone County)

Mozart (Stone County) Onia (Stone County)

Onia (Stone County) Optimus (Stone County)

Optimus (Stone County) Rushing (Stone County)

Rushing (Stone County) Sherman, Harold Morrow

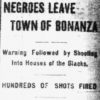

Sherman, Harold Morrow Sundown Towns

Sundown Towns Turkey Creek (Stone County)

Turkey Creek (Stone County) Arkansas Folk Festival

Arkansas Folk Festival  "The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood

"The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood  Blanchard Springs Caverns

Blanchard Springs Caverns  Blanchard Springs Caverns

Blanchard Springs Caverns  Blue Mountain School

Blue Mountain School  Jimmy Driftwood

Jimmy Driftwood  Jimmy Driftwood

Jimmy Driftwood  Hanover Church

Hanover Church  Hess/O'Neal Ferry

Hess/O'Neal Ferry  Mirror Lake

Mirror Lake  Mountain View Town Square

Mountain View Town Square  North Sylamore Creek

North Sylamore Creek  Ozark Folk Center

Ozark Folk Center  Ozark Folk Center Blacksmith

Ozark Folk Center Blacksmith  Dick Powell

Dick Powell  Roasting Ear Creek Baptism

Roasting Ear Creek Baptism  Stone County Courthouse

Stone County Courthouse  Stone County Map

Stone County Map  Sylamore Creek

Sylamore Creek  Syllamo Mountain Bike Trail

Syllamo Mountain Bike Trail  White River

White River

Chief Syllamo did exist-he is documented by Jared C. Martin (state treasurer), whom he and Big Charley tried to kill. He lived mostly at the Methodist Camp near Riggsville. He is documented in the journals of A. C. Jeffery and J. J. Sams, as well by my great-grandfather, John Chitwood. He was one of the last of the Isyllamo, the Potato Clan of the Creek. The name Isyllamo means “my Jesus everywhere” in Algonquin. The name is Syllamo in a few places. Jeffery says that the Creeks took the name from old Syllamo. But the Creeks moved on in 1828 when the reservation ended, and Syllamo stayed. Isyllamo is pronounced “I Syl A Mo,” which to whites sounded like “I am Syllamo.” Sagamo means chief, and it’s likely that Isyllamo and Sagamo were combined to Sylamore. The Creek family of Isyallos put in the first trading post in 1816 at Sylamore. The name remained Sylamore until 1905 when the east side of the river, which now had the railroad, usurped the name and the Stone Co. side became Allison after a man named “Dad Allison” who had served in the Civil War; he’s buried at Gayler Creek Cemetery. Post offices were put in at Sylamore and Ruddells (Lime Co.), but both were gone by 1930. The last steamship docked at Stone County’s Sylamore in 1939, the year the bridge over the creek was built.