calsfoundation@cals.org

Union County

| Region: | Southwest |

| County seat: | El Dorado |

| Established: | November 2, 1829 |

| Parent counties: | Clark, Hempstead |

| Population: | 39,054 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 1,039.07 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

640 |

2,889 |

10,298 |

12,288 |

10,571 |

13,419 |

14,977 |

22,495 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

30,723 |

29,691 |

55,800 |

50,461 |

49,686 |

49,518 |

45,428 |

48,573 |

46,719 |

45,629 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

41,639 |

39,054 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

23,216 |

59.4% |

| African American |

12,729 |

32.6% |

| American Indian |

150 |

0.4% |

| Asian |

280 |

0.7% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

16 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

1,045 |

2.7% |

| Two or More Races |

1,618 |

4.1% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

1,754 |

4.5% |

| Population Density |

37.6 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$44,663 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$25,193 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

19.1% |

|

At more than 1,000 square miles, Union County is the state’s largest county geographically. Ninety percent of the county is forested. Forage and hay are grown for livestock, but few row crops are cultivated. Nearly one-quarter of the work force is employed in manufacturing, primarily in petrochemical, poultry processing, and wood products operations.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In November 1829, the territorial legislature formed Union County from parts of Hempstead and Clark counties. The next spring, the county court convened at the former colonial trading post of Ecore Fabre (now Camden in Ouachita County) on a bluff overlooking the Ouachita River. In 1837, county officers anticipated that a pending division of the county would slice away the Ecore Fabre region and approved the relocation of the county seat farther down the river to another port, Scarborough’s Landing (later renamed Champagnolle). The community of New London in eastern Union County was first settled in 1839.

Over the following two decades, three counties and parts of six others were carved from the original Union County. Reflecting a changing economy, many residents in 1843 signed a petition requesting that the county seat be moved inland from the river floodplain and closer to major cotton farms. Three commissioners asked Matthew Rainey to surrender 160 acres he had preempted on a ridge that was the county’s highest point, about twelve miles from the river. A surveyor platted the newly christened El Dorado, and officials approved $200 to build a courthouse on the town square.

Immigrants from Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi spurred a rapid population growth in the 1840s, followed by a slower rise in the next decade. More than half of the 12,288 residents in 1860 were slaves. About five percent of the landholders were planters (holding twenty or more slaves), and a third of the county’s slaves labored on these larger farms. Besides growing corn, Union County was second in the state in the production of peas, beans, and sweet potatoes.

By 1833, Methodist circuit riders were conducting church services in cabins, while a Primitive Baptist congregation met in the southeast part of the county. About 1843, residents of Scotland, immigrants from the Carolinas who clung to their Scottish ancestry, organized the first Presbyterian church; soon after, he Reverend William Lacy from that congregation established a Presbyterian church in the new county seat. Records indicate that a school was operating in south Union County by 1838. In 1843, Lacy and his wife, Julia, formed El Dorado’s first private academy in their small home. After two years, he left to manage his plantation and turned his students over to Elizabeth Banks, who founded what became El Dorado Female Institute (and later the site of South Arkansas Community College). The school occupied land donated by Albert Rust, the first U.S. congressman from Union County.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The county had a population of 5,957 white citizens in 1860, with an enslaved population of 6,331. The proportion of enslaved African Americans compared to the white population demonstrates the county’s reliance on the institution of slavery. Both representatives to the 1861 Secession Convention owned enslaved people, with William Tatum owning eighteen and Hezekiah Bussey owning eleven.

A planter dedicated to stability and order, Rust was skeptical of secessionist radicals. Yet by the time Arkansas seceded in May 1861, Rust favored disunion and would become a Confederate brigadier general. Though local historians boasted that 1,200 to 1,500 Union County men mustered into the Confederate military, the 1860 census counted only 1,219 white males age twenty to fifty. As was true elsewhere in Arkansas, some landowners set out for Texas with their slaves during the war. No battles were fought in Union County, although residents suffered from bushwhackers as Confederate control of southwestern Arkansas diminished.

White landowners had enjoyed considerable wealth in antebellum Union County. While the war led to widespread devastation, prewar plantation families retained their land and position. Falling cotton prices throughout the late nineteenth century pushed many farmers into tenancy, but this was less pronounced in Union County than in other old plantation districts. Immigrants in the 1870s spurred a rise in Black residents that exceeded the increase in the county’s white population. The newcomers forged new lives in the midst of the faltering cotton economy. Black land ownership at the turn of the century exceeded state averages. In 1870, Reverend Joseph Henry became the first pastor of the El Dorado Baptist Church, which became the largest Black congregation in the county.

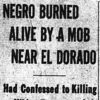

Multiple incidents of extrajudicial violence occurred in the county in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with many of the acts racially motivated. African American Jerry Atkins was lynched in 1865 after allegedly killing two white children as they walked to school. Four men reportedly lost their lives in 1873 for an alleged attack on a white woman. A decade later, Albert Williams was killed by a mob after being accused of attacking a white girl.

The Gilded Age through Early Twentieth Century

By 1897, a school for Black students in El Dorado was in session. In 1908, Washington High School began enrolling generations of African Americans; it closed in 1969 under district-wide integration. The El Dorado Junior College operated in the county from 1928 to 1942, preparing white students for admission to universities. It closed due to a lack of enrollment during World War II.

The construction of railroads in the 1890s led to the county’s greatest economic transformation between the Civil War and the 1920s oil boom. On July 4, 1891, the first passenger train arrived in El Dorado from Camden on a line that the St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern quickly acquired. The railroads created the local timber industry. In 1892, J. S. Cargile formed a partnership with some El Dorado businessmen to build a sawmill and a town for workers on Lourtre Creek. The partners formed the Arkansas Southern rail company to extend the Iron Mountain line from El Dorado to the mill. This transit artery led to the founding of Smackover and Junction City as rail terminals; the Union Saw Mill Company built a line in 1904 to the new mill site of Huttig, soon the county’s largest sawmill community. This north-south network supplanted the east-west system between the old river landings and the interior region. Other towns founded with a timber-based economy include Calion, Felsenthal, and Strong.

The Tucker-Parnell Feud erupted in 1902 and continued for several years. The feud led to the deaths of several county residents and led to accusations of judicial misconduct.

The advent of automobiles and fuel demands during World War I sparked oil exploration in the region. The first Union County leases were bought in 1914, but initial test wells near Urbana and the Columbia County line were dry. In 1921, Dr. Samuel Busey, who had invested in oil leases in Bolivia, arrived in El Dorado and quickly bought a hotel and interest in an oil well. On January 10, 1921, his well erupted with a thick column of oil that soiled clothes on wash lines a mile away. The rural market center was unprepared to become a boomtown. Hotels and rooming houses overflowed, and tent-covered cot spaces, restaurants, and shops went up along South Washington Street. A newspaper reporter noted that a person walking along what became known as “Hamburger Row” could “purchase almost anything from a pair of shoes to an auto, an interest in a drilling tract or have your fortune told.”

Smackover became the second oil boomtown when a discovery oil well confirmed in July 1922 what an earlier gas explosion at a well site near the present site of Norphlet had indicated: the Smackover field held tremendous reserves of crude. Sidney Albert Umsted led efforts to develop the field. By 1925, nearly 3,500 wells were pumping sixty-nine million barrels of oil, the greatest rate in the world. The influx of wildcatters and oil field workers overwhelmed local authorities.

The oil booms introduced a new industrial elite into a state where the alluvial cotton-growing region had been the traditional source of wealth. For the rest of the twentieth century, Union County was at the top of per capita income for the state. The county also was among the first to suffer from industrial pollution. The saltwater that surfaced with oil was released to turn surrounding creeks into undrinkable bogs and forests into a scorched landscape. A visitor arriving by train in 1937 recalled, “I wondered what I had come to, it looked like a moonscape.” Environmental efforts would not begin to undo the damage until the end of the century.

Without effective state regulation, drillers ignored basic recovery practices, and production declined markedly by the 1930s. But the county found relief from the Great Depression when the Lion Oil Refining Company financed discovery wells in Shuler Field in 1937. Thomas H. Barton acquired the refining company in 1928 and soon joined Harvey Couch as one of the state’s most notable capitalists and its pioneering philanthropist. His financial support for the state livestock fair and the university medical school were accompanied by large donations to youth organizations. But Barton was a disappointed office seeker, losing to J. William Fulbright in the 1944 race for U.S. Senate. In 1956, Barton sold his company to the Monsanto Corporation. Charles H. Murphy, who took over Murphy Oil Corporation in 1941, kept the family-owned company headquartered in El Dorado and exerted statewide influence through membership on private and public governing boards.

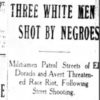

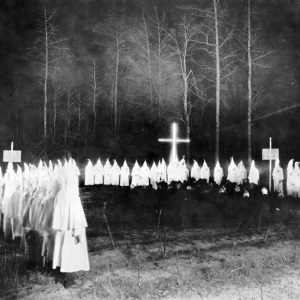

Racial violence continued to plague the county during this period. In 1910, the so-called El Dorado Race Riot led to the deaths of an unknown number of residents and the destruction of many African American homes and businesses. The same year, Sam Powell died at the hands of a mob after being accused of robbery and arson. Former soldier Frank Livingston was killed in 1919 after allegedly killing his employer and his wife. The Ku Klux Klan became active in the county in the 1920s, publishing the Arkansas Traveller newspaper. Hooded and robed men attacked African Americans in the Smackover area in late 1922 in an effort to drive out Black Arkansans involved in the oil industry. At least one man died in the attacks, although reports claimed that at least sixty-five people were killed or injured. The following year, Ed Brock was killed after being accused of attacking a white woman.

World War II through Modern Era

With the onset of World War II, Union County’s industrial base attracted the attention of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Entering a unique partnership with Lion Oil, the Corps supplied $28 million for construction of the Ozark Ordnance Plant to produce ammonium nitrate. The private company oversaw the operation of the plant and acquired it for a fraction of the construction costs at the end of the war. In 1983, the enterprise became El Dorado Chemical, which continued to make explosives as well as fertilizer. World War II encouraged dramatic growth in manufacturing, and state lawmakers authorized local communities to provide financial incentives to attract industry. The county received air service in the 1940s with the construction of South Arkansas Regional Airport. Union County established one of the first industrial development organizations, enticing Jess Merkle to build a large-scale poultry processing plant that became the largest employer in El Dorado. Beginning in 1965, Great Lakes Corporation processed the underground brine into a variety of brominated products, including flame retardants.

Racial violence continued to erupt in the county with the murder of Larry Wainwright in 1967. The Black teenager was allegedly killed by two white teenagers while walking along the street. Both of the accused were found not guilty, leading to a number of protests.

Despite the manufacturing expansion, the county’s population declined steadily after the war. Yet in the face of the loss of manufacturing jobs throughout the state in the 1990s, that sector held its own in the county. New glossy brochures and websites integrated tourism into the campaign to jolt the economy. These new advertisements highlighted the refurbishment in the 1990s of El Dorado’s downtown square into a historic district. The earliest commercial internet provider in the state, Information Galore, was founded and based in El Dorado.

Beginning early in the twentieth century, the Army Corps of Engineers built and maintained a lock and dam system designed to boost navigation on the Ouachita River. Although the shipped tonnage failed to match local economic boosters’ expectations, water-level management aided boating, hunting, and fishing. The navigation project sustained the Felsenthal National Wildlife Refuge, the world’s largest green-tree reservoir. The pools at the dams on the river provided an alternative water source in the early twenty-first century to the underground Sparta Aquifer, depleted by decades of industrial consumption.

Visitors to the county can visit the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in Smackover and the South Arkansas Arboretum State Park in El Dorado. The Newton House Museum in El Dorado, operated by the South Arkansas Historical Preservation Society, interprets the antebellum era. The Dual State Monument straddles the state line between Arkansas and Louisiana in southeastern Union County. Sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places include the Rialto Theater, Griffin Auto Company building, and El Dorado High School Gym.

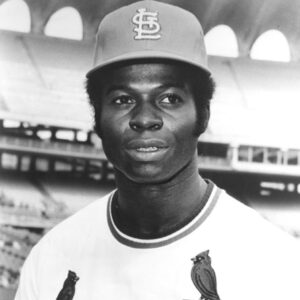

Famous residents of Union County include professional baseball players Lynwood Thomas “Schoolboy” Rowe and Lou Brock, as well as professional basketball player Reece “Goose” Tatum. Musicians Sleepy LaBeef, Jason Donald Williams, “Lefty” Frizzell, Ronnie Dunn, Cynthia Scott, and Floyd Cramer all spent time in the county during their early lives. Novelist Charles Portis was born in El Dorado, as was U.S. Representative Beryl Anthony and Donna Axum, the first Miss Arkansas to win the title of Miss America. Actor Gertrude Hadley Jeannette and photographer Richard Leo Johnson were both born in the county.

For additional information:

Buckalew, A. B., and R. W. Buckalew. “The Discovery of Oil in Southern Arkansas, 1920–1924.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Autumn 1974): 196–220.

Cordell, Anna Harmon. Dates and Data of Union County Arkansas, 1541–1948. Monroe, AR: Century Printing and Publishing Co., 1984.

Green, Juanita Whitaker. “The History of Union County Arkansas.” N.p.: 1954.

Kent, Caroline. “Uncle Sam Needs Your Resources: A History of the Ozark Ordnance Works.” South Arkansas Historical Journal 5 (Fall 2005): 4–20.

Parker, Scott. “A Changing Landscape: Environmental Conditions and Consequences of the 1920s Union County Oil Booms.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Spring 2001): 31–52.

Ragsdale, John G. “Shuler Drilling Company.” South Arkansas Historical Journal 1 (Fall 2001): 15–21.

Tracks and Traces. El Dorado, AR: Union County Genealogical Society (1977–).

Whitfield, Ben T. “El Dorado’s Two-Year Colleges.” South Arkansas Historical Journal 1 (Fall 2001): 4–14.

Ben Johnson

Southern Arkansas University

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Anthony, Beryl Franklin, Jr.

Anthony, Beryl Franklin, Jr. Atkins, Jerry (Lynching of)

Atkins, Jerry (Lynching of) Brock, Lou

Brock, Lou Bromine

Bromine Calion (Union County)

Calion (Union County) Dual State Monument

Dual State Monument El Dorado Race Riot of 1910

El Dorado Race Riot of 1910 Environment

Environment Felsenthal (Union County)

Felsenthal (Union County) Livingston, Frank (Lynching of)

Livingston, Frank (Lynching of) McRae, Thomas Chipman

McRae, Thomas Chipman New London (Union County)

New London (Union County) Norphlet (Union County)

Norphlet (Union County) Smackover Riot of 1922

Smackover Riot of 1922 South Arkansas Arboretum State Park

South Arkansas Arboretum State Park Strong (Union County)

Strong (Union County) Tucker-Parnell Feud

Tucker-Parnell Feud Whitworth, Donna Axum

Whitworth, Donna Axum Lou Brock

Lou Brock  Clearing Timber

Clearing Timber  Floyd Cramer

Floyd Cramer  El Dorado Courthouse Square

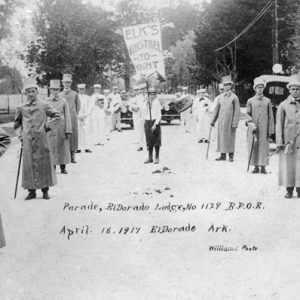

El Dorado Courthouse Square  El Dorado Elks Parade

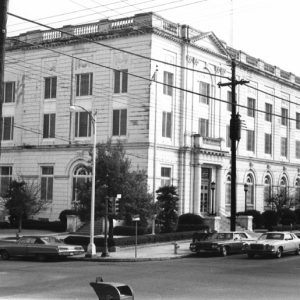

El Dorado Elks Parade  El Dorado Federal Courthouse

El Dorado Federal Courthouse  El Dorado Oil Company

El Dorado Oil Company  Ku Klux Klan Rally

Ku Klux Klan Rally  Sleepy LaBeef

Sleepy LaBeef  "Last Date," Performed by Floyd Cramer

"Last Date," Performed by Floyd Cramer  Oil Field Workers

Oil Field Workers  Albert Rust

Albert Rust  Smackover Oil Field

Smackover Oil Field  Three Creeks Methodist Church

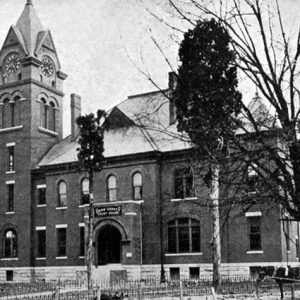

Three Creeks Methodist Church  Union County Courthouse

Union County Courthouse  Union County Courthouse

Union County Courthouse  Union County Gusher

Union County Gusher  Union County Map

Union County Map  Donna Axum Whitworth

Donna Axum Whitworth

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.