calsfoundation@cals.org

Washington County

| Region: | Northwest |

| County Seat: | Fayetteville |

| Established: | October 17, 1828 |

| Parent County: | Lovely |

| Population: | 245,871 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 941.47 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

|

|

2,182 |

7,148 |

9,970 |

14,673 |

17,266 |

23,844 |

32,024 |

34,256 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

33,889 |

35,468 |

39,255 |

41,114 |

49,979 |

55,797 |

77,370 |

100,494 |

113,409 |

157,715 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

203,065 |

245,871 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

168,351 |

68.5% |

| African American |

8,652 |

3.5% |

| American Indian |

3,573 |

1.5% |

| Asian |

5,718 |

2.3% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

8,799 |

3.6% |

| Some Other Race |

24,958 |

10.2% |

| Two or More Races |

25,820 |

10.5% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

44,755 |

18.2% |

| Population Density |

261.2 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$50,451 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$27,790 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

16.4% |

|

Washington County, named for President George Washington, is in the northwestern corner of Arkansas in the Ozark Mountains. It was established on October 17, 1828, formed from Lovely County, which was part of Indian Territory. Washington County has grown from small settlements of farms, mills, and orchards into one of the most affluent and prosperous counties in the state. The University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville remains the flagship of the University of Arkansas system. Tyson Foods, Incorporated is headquartered in nearby Springdale (Washington and Benton counties) and has become a leading provider of jobs in the region. Given the broad range of manufacturing, industrial, and retail businesses, the population of Springdale is quite diverse, including a large Hispanic community as well as many Marshall Islanders.

Pre-European Exploration

Paleoindian peoples appear to have reached northwestern Arkansas by 8500 BC. This culture manufactured a distinctive lanceolate spear point and used a stone-working technology developed by upper Paleolithic groups from Europe and northern Asia. Collectively, these artifacts are called Clovis points, which were components of a sophisticated weapon system consisting of a multi-piece dart and throwing stick that increased the velocity with which the dart could be thrown. Clovis materials have been found in present-day Washington County, though in limited quantities, likely due to the rugged terrain of the Ozark Mountain region being a poor place for settlement. Although evidence of Paleoindian presence in Washington County is sparse, the Dalton culture that followed is better represented in the county.

European Exploration and Settlement

The Mississippian Period refers collectively to the cultural developments throughout the mid-South from approximately AD 900 to 1600, around the time of the expedition of Hernando de Soto. The written accounts of the de Soto expedition, combined with recent archaeological studies, have demonstrated that there was an upsurge in population, a rise in agricultural development, and the development of small farming communities throughout the Ozarks. The soil of the future Washington County supported a diverse yield of crops, such as corn, beans, and squash. The clearing of forested areas to obtain new farming lands would become commonplace for European settlers, but the area was not heavily populated before the nineteenth century.

The land that would become Washington County could not support intensive, long-term agriculture. The environmental consequences of population stagnation and the overextension of the soil, combined with drought conditions and the transmission of European diseases, all were key underlying factors that kept the Native American population in the area relatively low throughout the early European involvement and settlement. Both Osage and Cherokee people hunted in the land during the early years of the nineteenth century, but neither established permanent settlements in the area.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Conflict between the Osage and Cherokee in what is now Washington County led to intermittent raids, which Indian agents and United States Army leaders attempted to end, often without success. William L. Lovely was assigned as the agent to the Western Cherokee by the U.S. government and sought to settle the dispute between the two warring tribes and the white settlers. In 1816, Lovely made the “Lovely Purchase” through an unauthorized sale of land from the Osage. The actual western border of the Cherokee land, which included portions of Washington County, was vague and remained unsurveyed until 1825.

On October 13, 1827, the Arkansas territorial legislature acted to create Lovely County. Present-day Washington County was within the borders of this county. The seat of Lovely County was established at Nicksville, Oklahoma. Many early settlers to Washington County came to the area after the establishment of Lovely County. The county was formed after the Cherokee were removed. History records the names of several white pioneer families who settled in what is now Washington County, among them Alexander, McGarrah, and Simpson. The first white families came to Washington County about a year before the Arkansas territorial legislature opened the area to white settlement, thus making trespassers of the new pioneers. These squatters lived on their homesteads, anticipating quick federal intervention to gain the land from the Cherokees, making it possible for permanent white settlement. The land formally became available to white settlement in 1828. There was a settlement at Cane Hill by 1827, and by the 1830s, villages appeared at Shiloh (now Springdale) and Fayetteville. Lovely County was abolished by October 14, 1828, most of it ending up, when the border was drawn, in Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). From much of what was left in Arkansas Territory, Washington County was formally created three days later.

Revivals or “camp meetings” of Baptists, Methodists, Episcopalians, and Cumberland Presbyterians played an important role in the county’s history. They provided spiritual and educational services to the settlers; they also afforded a social setting for the early pioneers. Many of these meetings were held in simple brush arbors built in the woods, and at least six camp meeting sites can still be found in Washington County that pre-date the Civil War. Black congregations also worshiped and held their own religious services before the Civil War. Religious meetings were held near Cane Hill, Lincoln, Fayetteville, and surrounding communities.

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, Washington County started to attract more affluent citizens. This is probably due to the good climate and availability of inexpensive land. Archibald Yell may be the most famous figure from early Washington County. In the 1830s, President Andrew Jackson appointed him a circuit court judge in the region. Yell built his home, Waxhaw, in Fayetteville and practiced law in and around Fayetteville. In 1836, he was Arkansas’s first congressman, and in 1840, he became Arkansas’s second governor. After he was killed in the war with Mexico, he was buried in Fayetteville. His law office is still preserved and maintained by the Washington County Historical Society.

The early settlers of Washington County placed great value on education, as evidenced by the many schools that dotted the county. The Cane Hill School was founded in 1835 for young men who planned to enter the ministry. The school first met in a log cabin but grew into Cane Hill College by 1850. In 1836, the Fayetteville Female Seminary was established for prominent young women of the city by Sophia Sawyer. Plans to open an institution named Far West Seminary in the 1840s never came to fruition, but the Ozark Institute, a school for boys, operated for several years at the site of the planned seminary. Arkansas College, a Disciples of Christ institution, operated in Fayetteville from 1850 until the Civil War.

At least two incidents of extrajudicial violence took place in the county before the Civil War. In 1839, four men were lynched in Cane Hill after being accused of the mass murder of five people in the community. Two enslaved men, Aaron and Anthony, lost their lives at the hands of a lynch mob in 1856 after allegedly killing their owner. Another enslaved man was lynched in 1860.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The 1860 federal census recorded the population of the county as 13,166 white citizens, forty-seven free people of color, and 1,432 enslaved people. While the number of enslaved people was lower than in many counties in southern and eastern Arkansas, they did make up almost ten percent of the total population in Washington County.

On February 18, 1861, the citizens of Washington County were asked to vote for or against a state convention that would consider secession. They rejected the call for a convention by almost a three-to-one margin. Unionist sentiment rang strong in the county—Jonas M. Tebbets, one-time member of the Arkansas state legislature and attorney for the Fayetteville branch of the State Bank, was briefly imprisoned at Fort Smith (Sebastian County) for his Unionist views in May 1861. At the May statewide convention on the issue of secession, chaired by Washington County resident David Walker, delegates from Washington County voted to remain loyal to the Union. Finding themselves outvoted 65-6, the four delegates reversed their votes, leaving Isaac Murphy of Madison County alone in opposition to secession. A total of four men represented Washington County at the convention, the most of any county. At least two of the representatives owned enslaved people at the time of the 1860 census.

During the Civil War, Washington County represented a coveted prize for both sides. It was only a day’s ride into Unionist Missouri, where both the Union and Confederate soldiers might find aid and support. The two great battles fought in northwestern Arkansas—Pea Ridge on March 6–8, 1862, and Prairie Grove on December 7, 1862—involved attempts by Confederates to solidify their control over the area and seize control of southern Missouri. The Federal forces won both engagements and were thus able to keep Missouri in the Union.

Washington County, like so many counties in the state, provided troops to both Union and Confederate armies. Confederate general Ben McCulloch issued a call for troops that resulted in several hundred enlistments from Fayetteville. Peter Mankins Jr. of the Middle Fork Valley raised a company of eighty-four men and personally equipped sixty-four for the Confederate force. Washington County and the surrounding territories also fielded two cavalry regiments, two infantry regiments, and one artillery corps for the Union army. Washington County and the surrounding area fielded roughly 500 to 800 men for the Union and approximately 2,000 for the Confederacy.

Federal troops arrived in the county in February 1862, occupying Fayetteville. A number of engagements were fought in the county in the fall of 1862 before the Battle of Prairie Grove. An engagement at Oxford Bend in October led to a Union victory. Actions in the Cane Hill area include a skirmish on November 9, 1862, the Skirmish at Cane Hill on November 25, 1862, and the Engagement at Cane Hill, fought on November 28, 1862. The day before the Battle of Prairie Grove, there was an action at Reed’s Mountain.

The Action at Fayetteville on April 18, 1863, demonstrated the dichotomy of the Civil War. The First Arkansas Cavalry (Confederate) engaged the First Arkansas Cavalry (Union) force around 9:00 a.m. The rebels, led by Brigadier General William Lewis Cabell, enacted a desperate charge against the Union flank only to meet a tumultuous crossfire. The Federal troops had amassed a sizeable amount of ordnance upon College Avenue. The Confederates slowly withdrew when it became apparent that they would be unable to advance.

Three weeks after the Action at Fayetteville, the Union forces withdrew to Springfield, Missouri, and the rebels were able to occupy peacefully the town that they had failed to seize by arms. The town changed hands several times throughout the war. Other engagements took place at the White River on March 22, 1863; Fayetteville on August 23, 1863; McGuire’s on October 12, 1863; Fayetteville on June 24, 1864; Elm Springs on July 30–31, 1864; Richland Creek on August 16, 1864; and Cane Hill on November 6, 1864.

After the war, men returned to find schools burned, fields in disarray, orchards destroyed, and fences and barns razed for firewood. Fayetteville, as well as the entire county, lost a great deal in trade, commerce, men, and infrastructure throughout the bloody conflict.

By the beginning of 1866, shops began to reopen, and life seemed to improve. The stage from Springfield, Missouri, resumed operation, and the mills were rebuilt at Rhea, Clear Creek, and Cane Hill. Cane Hill College was rebuilt and opened in 1868 by its long-serving president, Fontaine R. Earle. The first public school for former slaves, the Mission School, opened in 1866. It was formed by a former Union cavalry officer, Lafayette Gregg, and was supervised by Ebenezer E. Henderson, who was initially deeply resented by many of the white citizens of the county. The school was the first post–Civil War school for Black students in the county. Students were also taught informally elsewhere in the region by Black teachers in churches and houses.

The University of Arkansas, originally known as Arkansas Industrial University, formally opened on January 22, 1872. The university started with eight students, a dozen books, acting president Noah P. Gates, and one teacher, Charles H. Leverett. By the end of the year, enrollment had reached 101 students from towns throughout the county and the state.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

From the 1870s to the 1900s, the county population increased steadily, as did farm yields. In 1870, the population was 17,266; by 1900, it had grown to more than 34,000. By 1870, there were only 73,145 acres under cultivation. The average acreage increased to almost 238,000 by 1900. Apples, grapes, strawberries, corn, and assorted livestock provided the fundamental agricultural base throughout the twentieth century.

Fruit production had also become a strong source of revenue for the county’s farmers by the close of the nineteenth century. Apples had long been a basic crop for Washington County. As early as 1852, area farmers sent crates of their “striped Ben” apples across the Boston Mountains to sell at ports along the Arkansas River. Orchard production remained small until after the Civil War. Agriculture received a great boost with the use of the St. Louis, Arkansas, and Texas Railway line. It was completed in 1882 with the opening of the Winslow Tunnel and provided a quick, reliable mode of transportation for commerce. Washington County’s apple harvest was the highest in the state in 1890, with 211,685 bushels; by 1900, production had nearly tripled to 614,924. The Western Arkansas Fruit Growers and Shippers Cooperative Association, which organized in Springdale in 1888, provided a surge in growing, producing and marketing activities to the booming orchards. Springdale College operated for several years at the end of the nineteenth century.

Early Twentieth Century

By 1900, Washington County was exporting fence posts, hardwood lumber, railroad ties, spokes, and posts throughout the nation. The large-scale clearing of land, mostly in the southern portion of the county, afforded new opportunities for settlers to farm and grow fruit, thus creating a thriving canning and evaporating business.

The shipment of goods by rail began to be replaced by trucks in the early twentieth century. Jones Truck Lines, founded by Harvey Jones, began operations in Springdale in 1918, serving local businesses before expanding service across the country over the next several decades.

The fruit business peaked then waned in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Poor soil fertility and less cultivated acreage appeared to be the key underlying factors in the reduction in fruit production. The timber boom left a vast amount of open arable land. Farming was attempted on the denuded land, especially fruit and vegetable production, but erosion quickly removed the topsoil and made farming impractical.

Created to educate young women in the Ozarks, the Helen Dunlap School for Mountain Girls operated in Winslow between 1905 and 1938. Students learned typical school subjects as well as practical skills.

The oldest radio station in the state began broadcasting in 1923 as KFMQ. It continued to operate in the twenty-first century as KUOA.

World War II through the Faubus Era

The Aaron Poultry and Egg Company created the county’s first modern poultry processing farm in 1914 at an old mill building on Dickson Street in Fayetteville. In 1916, the Aaron Company decided not to build a permanent plant in Fayetteville, but Jay Fulbright, the father of U.S. Senator J. William Fulbright, along with other investors built a processing plant on West Avenue in Fayetteville. The company improved local stock both in egg production and the quality of roosters. Chickens slaughtered in the Fayetteville plant were shipped to markets throughout the nation. The plant grew and changed owners and was eventually acquired by the Campbell Soup Company in 1955. The years following World War II proved a boon for Tyson Foods of Springdale, which began an era of rapid expansion.

Schools in Fayetteville were among the first in the state to integrate. Fayetteville High School integrated in 1954, immediately after the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Fayetteville Junior High School integrated gradually over the next several years with elementary schools integrating slowly over the next decade.

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform

Ecclesia College, a Christian college, is located in Springdale. Founded in 1975 as a training center for missionaries, it received accreditation as a college in 2005; it was embroiled in a financial scandal in 2017.

Feed mills dot the landscape up and down U.S. Highway 71. This major thoroughfare cuts through the downtowns of Fayetteville and Springdale, the county’s two largest cities. There are several large poultry processing plants that employ over 1,000 workers each. The two largest are Campbell Soup of Fayetteville and Tyson Foods in Springdale, both located off Highway 71. Tyson Foods and George’s remain Washington County’s top poultry producers. They are still owned and operated by the same families that formed the businesses.

Beginning in 1888 and continuing throughout the twentieth century, Washington County has had the highest agricultural income of any county in Arkansas, employing over 50,000 agribusiness laborers. While nearly seventy percent of the county’s population lives in incorporated cities and towns, over half the county’s acreage is used for agricultural and recreational pursuits. Since Reconstruction, agriculture in Washington County has remained essentially unchanged, focusing on the raising of broilers, cattle, turkeys and hogs. In addition, the county has significant commercial output of apples, grapes, strawberries, blueberries, and peaches. Despite having extensive agribusiness endeavors, Washington County remains a leader in education and industry, as reflected by the thousands of professionals employed by the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, the Campbell Soup Company, and Tyson Industries.

Communities in the county include Elkins, Elm Springs, Farmington, Johnson, Prairie Grove, West Fork, Winslow, Tontitown, Goshen, and Greenland. Historic communities include Maguiretown and Mount Comfort.

Attractions and Famous Residents

Attractions in the county include many sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Woolsey Farmstead Cemetery, Fayetteville Confederate Cemetery, Springdale Poultry Industry Historic District, Prairie Grove Airlight Outdoor Telephone Booth, and Fitzgerald Station and Farmstead. Devil’s Den State Park is a popular camping area. The Tontitown Grape Festival is well attended every year, and the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History preserves local heritage.

Famous residents of Washington County include U.S. Senator James David Walker, interior decorator Paul Martin Heerwagen, astronomer and mathematician Herbert Earle Buchanan, and historian David Yancey Thomas. Bacteriologist Margaret Pittman was born in the county, as was pharmacist, mayor, and businesswoman Virginia Maud Dunlap Duncan. Both newspaper publisher Roberta Waugh Fulbright and her son, U.S. Senator Bill Fulbright, resided in Fayetteville and are buried in the city.

For additional information:

Anderson, Peg. Washington County, Arkansas. Fayetteville, AR: League of Women Voters of Washington County, 1982.

Banes, Marian Tebbetts. The Journal of Marian Tebbetts Banes. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, n.d.

The Battle of Prairie Grove: Record with Mementos of December 7, 1862. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1992.

Blevins, Brooks. Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Campbell, William S. One Hundred Years of Fayetteville: 1828–1928. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1928.

Flashback: Preserving the Past for the Future. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society (1951–).

Flashforward. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society (1996–).

History of Benton, Washington, Carroll, Madison, Crawford, Franklin and Sebastian Counties, Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1889.

History of Washington County, Arkansas. Springdale AR: Shiloh Museum, 1989.

Lemke, W. J. Historic Washington County, Arkansas. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1952.

Mahan, Russell L. The Battle of Fayetteville, Arkansas: April 18, 1863. Centerville, UT: Historical Enterprises, 1996.

Smith, T. J. “Slavery in Washington County, Arkansas, 1828–1860.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1995.

Winn, Robert G., ed. Railroads of Northwest Arkansas. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1986.

Matthew Bryan Kirkpatrick

Washington County Historical Society

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Arkansas River and Prairie Grove, Skirmishes at

Arkansas River and Prairie Grove, Skirmishes at Arkansas State Boundaries

Arkansas State Boundaries Bobby Hopper Tunnel

Bobby Hopper Tunnel Cane Hill, Engagement at

Cane Hill, Engagement at Devil's Den State Park

Devil's Den State Park Elkins (Washington County)

Elkins (Washington County) Elm Springs (Washington and Benton Counties)

Elm Springs (Washington and Benton Counties) Farmington (Washington County)

Farmington (Washington County) Fayetteville, Action near (July 15, 1862)

Fayetteville, Action near (July 15, 1862) Goshen (Washington County)

Goshen (Washington County) Greenland (Washington County)

Greenland (Washington County) Maguiretown (Washington County)

Maguiretown (Washington County) Mount Comfort (Washington County)

Mount Comfort (Washington County) Oaks Cemetery

Oaks Cemetery Pig Trail Scenic Byway

Pig Trail Scenic Byway Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park

Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park Reed's Mountain, Skirmish at

Reed's Mountain, Skirmish at Richland Creek, Skirmish at (August 16, 1864)

Richland Creek, Skirmish at (August 16, 1864) Rodeo of the Ozarks

Rodeo of the Ozarks Southern Memorial Association of Washington County

Southern Memorial Association of Washington County Southwest Experimental Fast Oxide Reactor (SEFOR)

Southwest Experimental Fast Oxide Reactor (SEFOR) Tebbetts, Jonas March

Tebbetts, Jonas March Washington County Courthouse

Washington County Courthouse West Fork (Washington County)

West Fork (Washington County) Pietro Bandini

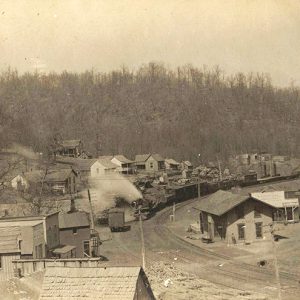

Pietro Bandini  Brentwood Street Scene

Brentwood Street Scene  Cane Hill College

Cane Hill College  Cane Hill Street Scene

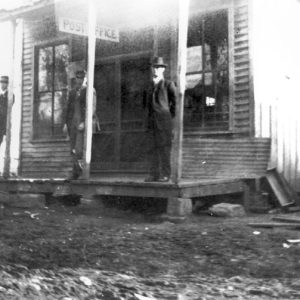

Cane Hill Street Scene  Cincinnati Post Office

Cincinnati Post Office  Devil's Den State Park

Devil's Den State Park  Devil's Den State Park

Devil's Den State Park  Maud Duncan Museum

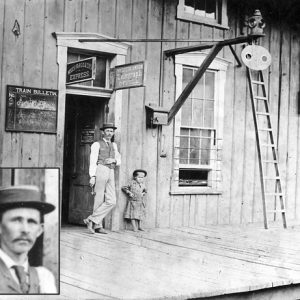

Maud Duncan Museum  Durham Depot

Durham Depot  Farmington Post Office

Farmington Post Office  Fayetteville Federal Courthouse

Fayetteville Federal Courthouse  Fayetteville Female Seminary

Fayetteville Female Seminary  Lafayette Gregg Home

Lafayette Gregg Home  Headquarters House Museum

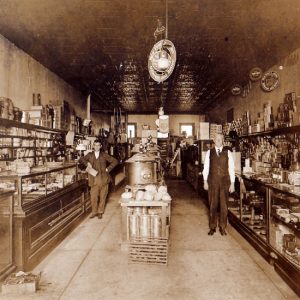

Headquarters House Museum  J. M. Karnes Store

J. M. Karnes Store  Lincoln American Legion Post

Lincoln American Legion Post  Lincoln Train Depot

Lincoln Train Depot  Maguiretown Store and Lodge

Maguiretown Store and Lodge  Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park

Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park  Prairie Grove Physicians

Prairie Grove Physicians  Prairie Grove Street Scene

Prairie Grove Street Scene  William H. Rhea

William H. Rhea  Sarah Bird Northrup Ridge House

Sarah Bird Northrup Ridge House  Segregated Waiting Room

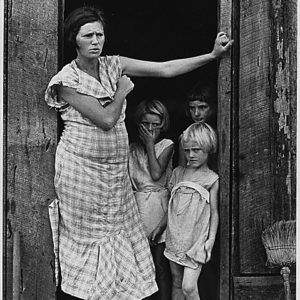

Segregated Waiting Room  Sharecropper Family

Sharecropper Family  Southern Mercantile Store

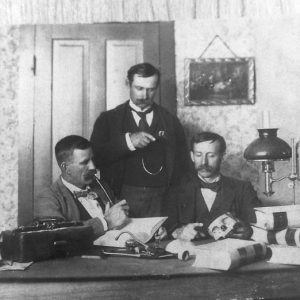

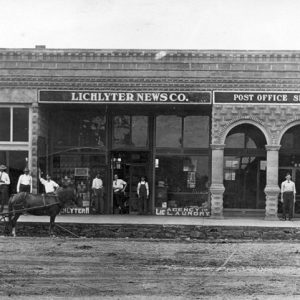

Southern Mercantile Store  Springdale Newspaper and Post Office

Springdale Newspaper and Post Office  Test Excavations

Test Excavations  University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville  University of Arkansas's First Buildings

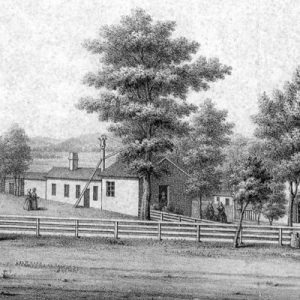

University of Arkansas's First Buildings  Walton Arts Center

Walton Arts Center  Washington County Courthouse

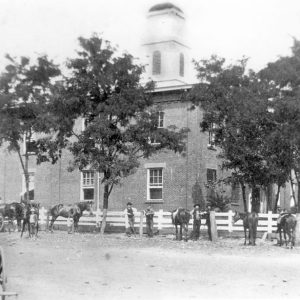

Washington County Courthouse  Old Washington County Courthouse

Old Washington County Courthouse  Washington County Fairgrounds

Washington County Fairgrounds  Washington County Map

Washington County Map  George Washington

George Washington  White River Bridge at Elkins

White River Bridge at Elkins  White River Bridge at West Fork

White River Bridge at West Fork  Winslow Street Scene

Winslow Street Scene  Winslow Street Scene

Winslow Street Scene  Archibald Yell's House

Archibald Yell's House  Zerbe Air Sedan

Zerbe Air Sedan  Zero Mountain Caverns

Zero Mountain Caverns

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.