calsfoundation@cals.org

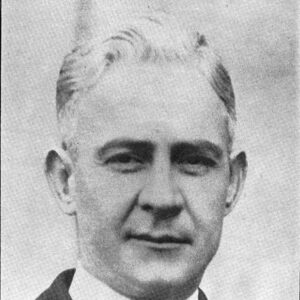

William Reynolds Dyess (1894–1936)

William Reynolds Dyess was a politician and government official who headed the Arkansas operations for two New Deal agencies: the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The cooperative farming community known as Dyess (Mississippi County) was named in his honor following his death in a plane crash.

William Reynolds Dyess was born in July 1894—the exact date is unknown—near Waynesville, Mississippi, to William Henry Dyess and Martina (Mattie) Eudora Bass Dyess. He had a brother and a sister. He initially worked as both a contractor and a farmer in Mississippi before moving to Arkansas in 1926 to take a job as the superintendent of construction for a company doing levee work on the Mississippi and White rivers. In addition to the levee work, Dyess took advantage of his new location to engage in farming, although his father, who had also moved to Arkansas, oversaw most of the farming. Dyess’s early farms were in the Pecan Point (Mississippi County) area, but he and his father later bought a farm near Blytheville (Mississippi County). In 1930, Dyess bought a farm of his own near Osceola (Mississippi County), which would become his home.

Dyess entered politics, securing an appointment as a member of the Mississippi County Election Commission. In 1933, Dyess was appointed as the state’s FERA administrator. When that program was superseded in 1935 by the New Deal’s WPA, Dyess was named WPA administrator for the state. As state administrator of FERA and then the WPA, he oversaw the development of the cooperative farming community that would later bear his name. While what became known as the Dyess Colony Resettlement Area was technically a project of FERA, given that the agency was the source of its funding, the colony did not fit into the usual framework of the agency’s other rural rehabilitation project. Rather, it was more a reflection of Dyess’s vision.

As a farmer himself, Dyess brought experience and perspective to his implementation of the economic program that most New Deal agency administrators did not have. Dyess’s original plan called for 800 destitute farm families—tenant farmers and sharecroppers—to be placed on twenty- to forty-acre bottomland plots, each including a house. He envisioned the colony (Colonization Project No. 1 in the New Deal lexicon) becoming a self-supporting agricultural community. Funding limits eventually resulted in the plan being scaled back to 500 families, but even then it remained both the largest New Deal program of its kind, as well as a distinctive, pioneering effort, one that a local newspaper called “the only purely agricultural rehabilitation colony project in the nation this side of Alaska.” The colony was laid out with a town center serving as the hub and with the farms and homesteads stretching out from that communal center. Overseeing the daily activities of the population, and charged with implementing the plan, was a board of directors chaired by Dyess. As the plan unfolded in 1936, it seemed to represent the fulfillment of Dyess’s dream. One of the colony’s early residents was singer Johnny Cash, and national attention focused on Arkansas when First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the community in 1936. Dyess still attracts tourists to northeastern Arkansas in the twenty-first century.

Dyess’s efforts to shape and direct the development of Colonization Project No. 1 did not go unquestioned. As he gained more influence with some of the New Deal’s top officials, especially Harry Hopkins, rumors about a possible Senate or gubernatorial candidacy began to circulate, and possible political opponents started to raise questions about both Dyess’s political ambitions and his plans for the colony. To many, the land he had chosen as the site for the colony raised some major questions, as there were doubts in some circles about its suitability for farming, while others were concerned about the relationship between the sellers and Dyess. In 1934, FERA sent an investigative team to check out some of the allegations. While there was a minor issue with money spent to improve some non-colony roads, Dyess emerged more powerful than ever, with his critics dismissed as part of a “troublemaking” group of “radicals.”

However, Dyess was unable to see his vision come to fruition. On January 14, 1936, he was killed in a plane crash near Goodwin (St. Francis County). He was survived by his wife, Margaret Jackson Dyess, and their three children. Dyess is buried in Ermen Cemetery in Osceola. On May 22, 1936, the colonization project was renamed in his honor.

For additional information:

“Dyess Funeral at Osceola Tomorrow.” Arkansas Gazette, January 16, 1936, p. 7.

Hilburn, Robert. Johnny Cash: The Life. New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 2013.

Historic Dyess Colony: Boyhood Home of Johnny Cash. http://dyesscash.astate.edu/ (accessed October 22, 2021).

Pittman, Dan W. “The Founding of Dyess Colony.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Winter 1970): 313–326.

“Plane Falls near Brinkley, 17 Killed.” Arkansas Gazette, January 15, 1936, p. 1.

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Agriculture

Agriculture Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Levees and Drainage Districts

Levees and Drainage Districts Politics and Government

Politics and Government Canning at Dyess

Canning at Dyess  Dyess Colony

Dyess Colony  W. R. Dyess

W. R. Dyess

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.