calsfoundation@cals.org

Clinton Briggs (Lynching of)

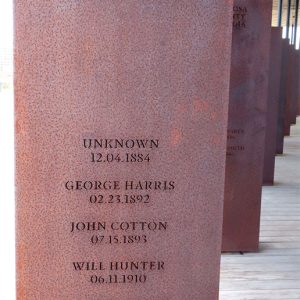

Clinton Briggs, a twenty-six-year-old soldier who had just returned to Star City (Lincoln County) after serving in the U.S. Army during World War I, was lynched on September 1, 1919, after allegedly insulting a young white woman.

According to the 1910 census, eighteen-year-old Briggs was living on a rented farm in Bartholomew Township, Lincoln County, with his parents, Sandy and Catherine Briggs. His father was a farmer, and Clinton was listed as a laborer. Clinton could both read and write, although he had not attended school.

On June 5, 1917, he registered for the draft. On his draft registration, he stated that he was working for a farmer named Alex Dutton. Briggs served in the army from June 19, 1918, until December 17, 1918. He was the recipient of the World War I Victory Medal and the World War I Victory Lapel Button. When he came back to Star City, he once again began to work on land owned by “Mr. Alex.” On March 15, 1919, he married Cora Goudes.

According to historian Nan Elizabeth Woodruff, like many African-American soldiers who returned to the South following World War I, Briggs found that his service to his country was a threat to the traditional, segregated southern way of life. He became a target of local whites, who wanted him to return to his former subordinate position. While walking down a sidewalk in early September 1919, Briggs reportedly stepped aside to allow a white couple to pass. Apparently, the white woman brushed into Briggs, scolding him by saying, “Niggers get off the sidewalk down here.” When Briggs replied, “This is a free man’s country,” the woman’s escort seized him until others came with an automobile and carried Briggs outside of town. Unable to find a rope to hang him with, the mob took the automobile chains, tied Briggs to a tree, and riddled his body with bullets. His body was found several days later by a farmer.

The September 4 issue of the Arkansas Gazette reported a somewhat different version of the events. According to its article, Briggs was employed on the farm of Mr. J. M. Bailey. Bailey’s daughter was driving a herd of cows to pasture when she passed Briggs, who was said to have made some insulting proposal to the girl. Upon hearing of the encounter, a group of unidentified men went to the Bailey farm, apprehended Briggs, and shot him to death. An inquest ruled that he was killed by unknown persons. A different account published in the same paper stated that Briggs had been arrested by the sheriff but was taken from him by a mob and shot.

In The Voice of the Negro 1919 (1920), Robert Thomas Kerlin, quoting the Whip (a Chicago, Illinois, publication), noted that the coroner had come to the usual verdict of death “by a mob of unknown persons.” There was apparently no interest in investigating the crime. Many of the African-American farmers in the area were threatening to leave, and many had already done so.

Giving some insight into the situation, Kerlin quoted the Hot Springs Echo in discussing discrimination against black soldiers in Arkansas. He noted that the American Legion in Little Rock (Pulaski County) was an all-white organization but had decided that sub-posts of African American veterans could be organized in each county “under the authority of local posts.” According to the Echo, “The American Legion was not so particular about its complexion being ‘lily-white’ when it came to ‘looking the Germans in the eye.’ For valor displayed in the recent war, it seems that the Negro’s particular decoration is to be the ‘double cross.’”

For additional information:

“Arkansas Mob Kills Negro Soldier.” Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia), September 3, 1919, p. 21.

Kerlin, Robert Thomas. The Voice of the Negro 1919. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1920. Online at https://archive.org/details/voiceofnegro191900kerl (accessed September 16, 2021).

Mikkelsen, Vincent. “Coming from Battle to Face a War: The Lynching of Black Soldiers in the World War I Era.” PhD diss., Florida State University, 2007.

“Negro Killed by Mob at Star City.” Arkansas Gazette, September 4, 1919, p. 14.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Briggs Lynching Article

Briggs Lynching Article  Lincoln County Lynching

Lincoln County Lynching

Clinton Briggss grandfather, Elijah Henderson, the father of his mother Catherine, of Tensas, Parish, Louisiana, was a member of Company I, 51st U.S. Colored Infantry in the Civil War. He enlisted in 1863 in Vicksburg, Mississippi. We have set up the Sandy and Catherine Henderson Briggs Facebook site to share our family history with our younger Briggs family members. The Clinton Briggs story touched their hearts. We have nearly 150 members on the site and have posted information that includes the conveyance of Elijah Henderson and his mother during slavery. Catherine Henderson married Sandy Briggs in Tensas Parish, and the family migrated to Lincoln County, Arkansas, around 1890 or after. The Arkansas Gazette version of the lynching of Clinton Briggs is not as reliable as other incidents reported by the Arkansas Gazette during that time. The Vincent Mikkelsen version matches the oral history report by our family members. Clinton Briggs was also castrated, as was sometimes done with lynching. Our older members that have passed on would become very emotional when discussing.