calsfoundation@cals.org

Bentonville (Benton County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 36º22’22″N 094º12’31″W |

| Elevation: | 1,280 feet |

| Area: | 33.84 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 54,164 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | April 3, 1873 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

696 |

1,677 |

1,843 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,956 |

2,313 |

2,203 |

2,359 |

2,942 |

3,649 |

5,508 |

8,756 |

11,257 |

19,730 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

35,301 |

54,164 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bentonville, the Benton County seat, has grown from a farming community to the home of the world’s largest retailer. Sam Walton, who started with a small store on the town square, built a retail giant but kept the Walmart Inc. headquarters in Bentonville. Bentonville is now one of the fastest-growing towns in the nation, largely because of the influx of Walmart Inc. suppliers. Some parts of the city are changing quickly, but preserved and restored buildings on the square and in adjoining neighborhoods help to maintain the look and feel of the historic town.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The first white settlers in what is now Bentonville arrived just a few years before the town was established in 1837. By that time, Osage Indians living in Missouri were no longer hunting in the area.

The legislature established Benton County on September 30, 1836, and called for the election of a three-man commission to select a county seat. On November 7, 1837, commissioners reported to the Benton county clerk, John B. Dickson, that they had laid out a square and 136 lots for Bentonville in the middle of the new county. Benton County and Bentonville were named for Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri. On May 31, 1997, a marker was dedicated near the home site of County Judge George P. Wallace, where the first county organizational meetings were held.

On December 31, 1836, John B. Dickson opened the Osage post office (renamed Bentonville post office on January 3, 1843). The county jail was built by 1837, and the first courthouse was in use by May 1838, in time for the second term of the county court. Bentonville grew slowly but steadily in its early years.

One group of Cherokee on the Trail of Tears (1837–1838) passed through Bentonville on its way to Indian Territory.

In 1857, Benton County became one of the first in Arkansas to establish a poor farm. All that remains is the Benton County Poor Farm Cemetery, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The Civil War took an enormous toll on the area. An action at Bentonville preceded the Battle of Pea Ridge, which was fought about twelve miles northeast of Bentonville, and troops moved through the town before and after the battle. There was also a skirmish in Bentonville the following year. During the war, most buildings in town, including the courthouse, were burned to the ground by forces from both sides; they destroyed buildings owned by those they suspected of sympathy with the other side, or to prevent the other side from using the buildings. Outlaws torched other buildings, and by the end of the war, only about a dozen houses stood in Bentonville. Bentonville was incorporated in 1873, but it was several years before the town began to recover from the war.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

Bentonville’s recovery did not begin in earnest until the 1880s. Many of the commercial buildings and residences built during this time still stand.

Tobacco-related businesses were operating in Bentonville in the 1870s and 1880s when tobacco production in the county far surpassed that of any other county in the state. Tobacco production declined in the 1890s as falling tobacco prices forced farmers to switch to other cash crops. Apples were the most successful.

The St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) (now operating as the Arkansas and Missouri) was completed through eastern Benton County in the summer of 1881 but missed Bentonville by almost six miles. Rogers (Benton County) was established along the tracks southeast of Bentonville, and in 1883, the Bentonville Railroad Company completed a rail line to Rogers. This track became part of the Arkansas and Oklahoma Railroad chartered in May 1898. By fall, the line extended through Bentonville and west to Gravette (Benton County), giving passengers, farmers, and merchants the option of using the Kansas City, Pittsburg and Gulf Railroad (now called Kansas City Southern) instead of the Frisco. In the next year, this line was continued to Grove, Oklahoma. In 1900, the Frisco bought this line and ran it until 1940. The spur from Rogers to Bentonville is still active.

These rail lines cutting across the region played an important role in the waning years of the tobacco industry and then played an essential role in the development of the apple industry. Apples—both whole and dried—were shipped to larger markets and were processed into vinegar, cider, or brandy. Apple-related businesses in Bentonville in 1903 included a large ice and cold storage plant along the tracks, six evaporators (where apples and other fruit crops were dried), and the Macon & Carson Distillery, said to be one of the world’s largest, which made applejack (apple brandy) near the town square.

The Peel House was constructed in 1875 and would eventually become the site for the Peel Mansion Museum and Heritage Gardens. The Bentonville College opened in 1895 but only lasted until 1901. New Home Church was built in the late 1890s and briefly had a school attached to it; the property is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The African-American population of Bentonville at this time was composed primarily of former slaves from throughout Benton County and their descendants; they were segregated into a portion of north Bentonville once known as “The Clique.” By 1888, the Bentonville Colored School offered classes through the eighth grade, and this building was also used by the Colored Baptist Church and for lodges for both men and women. There were two other segregated churches in this area.

Into the 1930s and 1940s, black students who wanted to attend high school had to move to a larger city where there was a high school for African Americans. Others moved away to find work. Most never moved back to Bentonville, but a few came back after retirement. As a result of this loss of young people, by the late 1940s, the school-age black population had decreased so much that the Bentonville Colored School was closed. At least one student was then sent by bus to the Colored School in Fayetteville (Washington County), but in the fall of 1955, the Bentonville school system was quietly integrated when one African-American student started the fourth grade.

Early Twentieth Century

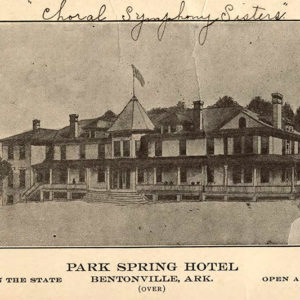

The Bentonville Confederate Monument was erected in 1908 (and removed in 2020 to be placed in a private park). The Bentonville Interurban trolley line, or Arkansas-Northwest Railroad, operated between Rogers and Bentonville beginning on July 1, 1914. J. D. Southerland owned the Interurban and the Park Springs Hotel, a large tourist resort in Bentonville. The Interurban provided transportation for tourists from the Frisco Railway Depot in Rogers to the Park Springs Hotel; it made its last trip on June 11, 1916.

The Great Depression arrived in Bentonville with a rapid series of business failures. The first closures included two large chains, Benton County Hardware Company and D & H Department Stores, in October 1930. Both Bentonville banks closed on December 6, 1930. Early in 1931, Jackson Dry Goods Company of Bentonville went into receivership, and soon other businesses were closed or in trouble. The town was not without a bank for long. On February 28, 1931, the Bank of Bentonville opened.

These events coincided with increased disease problems in the apple crop. By the early 1930s, farmers needed nine sprays to control problems such as San Jose scale, apple scab, codling moth, and Phoma spot. Many of the diseases and pests became immune to the sprays, leaving the farmer no choice but to destroy his orchard. Modern-day Bentonville has no orchards.

As the apple industry weakened, the chicken broiler business proved to be a successful alternative. By 1934, more broilers were raised in Benton County than in any other county in Arkansas. Railroads and other businesses that had been important to the success of the fruit industry were adapted for the poultry industry. In January 1941, the Peter Fox Company of Chicago leased space in the Bentonville Ice and Cold Storage plant to dress and pack chickens, which were then shipped by rail car to larger markets such as St. Louis, Missouri, and Chicago, Illinois, where they sold at premium prices.

World War II through the Faubus Era

The poultry industry in the area continued to expand during the war years. The Armour Company built a poultry dressing/packing plant in 1943. With the end of the war, companies such as the Kraft Cheese Company, Farm Bureau Poultry Processing, the Bentonville Casting Company, Wendt-Sonis, and Munsingwear Incorporated built plants that created jobs and strengthened the town’s post–World War II economy. Bentonville schools desegregated without publicity in the fall of 1955, although the low black population of the community meant that this involved only one black student being enrolled.

In 1950, Sam Walton bought the Harrison Variety Store on the town square. He remodeled the building and opened Walton’s 5 and 10 Variety Store on March 18, 1951. Over the next few years, Walton worked closely with the Bank of Bentonville; on August 31, 1961, he bought a controlling interest and was elected chairman of the board. On August 10, 1967, the Walton family opened Midtown Shopping Center downtown. In 1969, Walmart Inc. began building a warehouse and general office. Walmart Inc. stock went public in 1970 with 300,000 shares for sale at $16.50 each. On March 17, 1992, President George H. W. Bush presented Walton with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, describing him as “an illustration of the American dream” who helped to “bring economic prosperity to his community and to the nation.”

Modern Era

NorthWest Arkansas Community College was established in 1989 and has become the second largest community college in the state. Main Street Bentonville has established a downtown improvement district. The city now has its first library that was built specifically for that purpose and saw the opening of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in November 2011. The Bentonville Film Festival was established in 2015 Academy Award–winning actress Geena Davis; with corporate backing from Walmart, it seeks to promote diversity in the entertainment industry. In February 2020, another art museum, the Momentary, opened in a repurposed building in downtown Bentonville.

In the twenty-first century, Bentonville has become more ethnically diverse as the growing economy attracts immigrants to the region. For example, the Indian population more than tripled between 2010 and 2020, and the city’s first Hindu temple was founded in 2012.

In 2022, the U.S. National Mountain Bike Team announced that they would be based in Bentonville for training in preparation for the 2028 Olympics. This move had occurred following massive investment by the Walton Family Foundation to make northwestern Arkansas more bicycle-friendly.

The rapid growth of Bentonville in the early twentieth century has resulted in skyrocketing home prices, making affordable living for new transplants difficult. The Bentonville School District worked with a number of private partners, such as the local chamber of commerce, to develop affordable housing specifically for teachers, but despite the overwhelming support for the project, and the low cost for the community, the Bentonville City Council voted it down at its February 13, 2024, meeting.

Famous Residents

James Henderson Berry was a Confederate veteran, Bentonville lawyer, and judge of the 4th Judicial Court in 1882 when he was elected governor of Arkansas. He served one term as governor, then twenty-two years as a U.S. senator. After a long career on the national stage, he returned to Bentonville. Alfred Burton Greenwood was an early settler to the Bentonville area and served as a state representative, attorney, judge, congressman, and tax collector in support of the Confederacy.

A well-known graduate of the Bentonville Colored School was Arthur “Rabbit” Dickerson. He became a highly regarded businessman who ran a shoeshine business for more than fifty years, then became the first recipient and namesake of a Bentonville/Bella Vista Chamber of Commerce award for those who make special contributions to the community. Other recipients of the “Rabbit” Dickerson Award have included Sam Walton’s wife, philanthropist Helen Robson Walton.

Louise McPhetridge Thaden was born in Bentonville in 1905 and received her pilot’s license (signed by Orville Wright) in 1928. She set altitude, endurance, and speed records and, in 1936, became the first woman to win the Bendix Transcontinental Air Race. In 1951, Bentonville dedicated its municipal airport to her and rededicated it in 1976 when the city declared a Louise Thaden Week and Arkansas celebrated Louise Thaden Day. In 1998, the Bentonville/Bella Vista Chamber of Commerce established the Louise M. Thaden “Woman of the Year” award, which honors a woman who exemplifies the high standards and dedication demonstrated by Thaden.

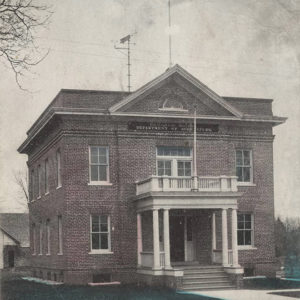

Albert Oscar Clarke (1859–1935) designed four buildings in downtown Bentonville including the Benton County Courthouse. All four are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Clarke’s designs inspired city planners to choose his work as a template for future downtown projects.

George Clark, a Bentonville native, became known nationally for his award-winning syndicated newspaper cartoons, “Side Glances” and “The Neighbors.”

Another well-respected Bentonville citizen was Dr. Neil E. Compton, a leader in the fight to prevent damming on the Buffalo River. In 1972, President Richard Nixon signed a bill to establish the Buffalo as the first national river. Compton spent many years preserving native trees and plants on his Bentonville property near the square. After his February 10, 1999, death, his home and property became the Conference Centre at Compton Gardens under the direction of the Peel House Foundation.

Asa Hutchinson, a well-known Republican politician who was born in Bentonville, was elected governor of Arkansas in 2014.

For additional information:

Black, J. Dickson. History of Benton County. Little Rock: International Graphics Industries, 1975.

City of Bentonville. http://www.bentonvillear.com/ (accessed April 13, 2022).

Farmer, Stephanie. “Walmart’s Company Town of Bentonville, Arkansas.” Jacobin, March 2021. https://jacobinmag.com/2021/03/walmart-walton-family-foundation-bentonville-arkansas-company-town (accessed April 13, 2022).

French, Chris. “Booming Bentonville: Loop Reactor Equipment in Action.” Water & Wastes Digest, March 2021. Online at https://www.wwdmag.com/wastewater-treatment/headworks/article/10939562/booming-bentonville-loop-reactor-equipment-in-action (accessed July 29, 2022).

Horton, Larry Layne. “A Beard Signifies Lice, Not Brains: The History of the Elkhorn Barber Shop Bentonville, Arkansas, 1888–1976.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2004.

Pascal, Olivia. “Corporate ‘Multiculturalism’ in Walmart’s Company Town.” Scalawag, May 3, 2018. https://scalawagmagazine.org/2018/05/corporate-multiculturalism-in-walmarts-company-town/ (accessed April 13, 2022).

———. “We’re Off to See the Waltons.” Dwell, June, 2, 2022. https://www.dwell.com/article/waltons-walmart-bentonville-arkansas-format-festival-806faff1-e1790679-e8e9baaf-0f9d3178 (accessed June 2, 2022).

Phillips, George H. Handling the Mail in Benton County, Arkansas, 1836–1976. Bentonville, AR: Benton County Historical Society, 1979.

Rosen, Marjorie. Boom Town: How Wal-Mart Transformed an All-American Town into an International Community. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2009.

Vranovci, Korab. “The Effects of Crystal Bridges in Downtown Revitalization of Bentonville, Arkansas, in the Last Decade.” MS thesis, University of Arkansas, 2018. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2758/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Don Warden

Siloam Springs Museum

Monte Harris

Rogers Historical Museum

Benton County Courthouse

Benton County Courthouse  Benton County Map

Benton County Map  Bentonville Main Street, 1921

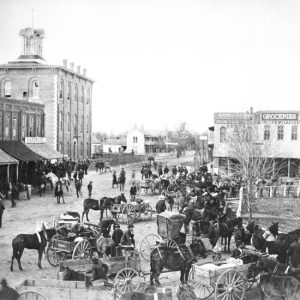

Bentonville Main Street, 1921  Bentonville City Square

Bentonville City Square  Bentonville Confederate Monument

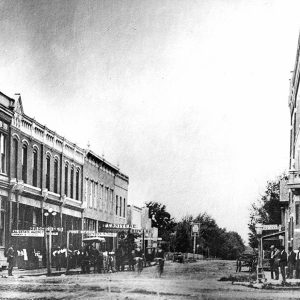

Bentonville Confederate Monument  Bentonville Street Scene

Bentonville Street Scene  Bentonville Street Scene

Bentonville Street Scene  Bentonville Street Scene

Bentonville Street Scene  Compton Gardens

Compton Gardens  Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art  Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art  Eagle Hotel

Eagle Hotel  Hotel Massey

Hotel Massey  Linebarger House

Linebarger House  Museum of Native American Artifacts

Museum of Native American Artifacts  Original Walton's

Original Walton's  Park Spring Hotel

Park Spring Hotel  Samuel W. Peel House

Samuel W. Peel House  Poor Farm Residences

Poor Farm Residences  Rowley's Esso

Rowley's Esso  Louise Thaden

Louise Thaden  Wal-Mart Visitors Center

Wal-Mart Visitors Center  Weather Station

Weather Station

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.