calsfoundation@cals.org

Frank Livingston (Lynching of)

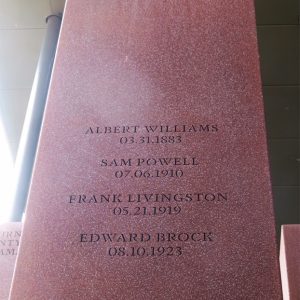

Former soldier Frank Livingston was burned alive at age twenty-five near El Dorado (Union County) on May 21, 1919, for the alleged murder of his employer. Livingston’s lynching was among several similar incidents in Arkansas involving returned African-American World War I–era servicemen.

In 1900, Frank Livingston was living in Cornie Township in Union County with his widowed father, Nelson. He was five years old at the time. (His mother was likely Lucy Willingham, whom Nelson had married in 1885.) By 1910, Nelson had remarried, and Frank remained in Union County with his father and stepmother, India. Although the 1910 census record indicates that he was born around 1893, subsequent draft records give his birthdate as November 1, 1892, in Shuler (Union County). Nelson Livingston and his two oldest sons, Ruf and Frank, were working as farmers on the “home farm.” Frank’s parents could read and write, but none of the children could. They owned their own farm, but it was mortgaged. (There was another Frank Livingston in Union County at the time, aged fifteen, working as a servant in the Garner home of Rufus and Emma Britt. This Frank Livingston apparently married Julie Parker in the Union County town of Wesson on March 8, 1918. The discrepancy in ages here makes it likely that this is not the Frank Livingston who was murdered in 1919.)

On June 15, 1917, Frank Livingston registered for the draft, listing himself as self-employed. He was stationed at Camp Pike in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) for two years, and when he was discharged, he returned to Union County and began to work for a local farmer the newspapers incorrectly identified as Robinson Clay, aged thirty-two; Livingston’s employer actually was William Robertson Clay. According to the Arkansas Gazette, on May 20, 1919, Livingston allegedly killed both Clay and Clay’s wife, Jessie. Apparently, Clay and Livingston were feeding livestock around 9:00 p.m. when they got into an argument. Livingston then returned to his house to get an axe and struck the farmer a fatal blow on the head. He then allegedly entered the house and used Clay’s gun to beat Clay’s wife to death. Following the murders, he allegedly dragged Clay’s body from the barn into the house and set the house on fire to conceal his crime. A group of African Americans nearby, attracted by the smoke, retrieved the charred bodies and notified the local sheriff. After discovering a bloody pair of pants supposedly belonging to Livingston on the scene, the sheriff assembled a posse. Groups of both whites and African Americans spread out in search of Livingston. He was captured on the morning of May 21 and forced to confess. A mob of 150 to 200, both black and white, prepared to lynch him at a point eighteen miles west of El Dorado. The sheriff learned about the capture, but by the time he had arrived at the site, Livingston had been tied to a tree and set on fire. Although the Gazette speculated that arrests would be made that day, it was not until a few days later that Governor Charles Brough instructed the Union County sheriff to use all means possible to apprehend the guilty.

In his doctoral dissertation on the lynching of black soldiers during the World War I era, Vincent Mikkelsen questions some of the reports that appeared in the Gazette, including the circumstances of Jessie Clay’s death and the fact that conclusions were drawn from incomplete evidence, given the burned state of the victims’ bodies. He also questions whether, as was often the case, blacks were coerced to participate in the lynching. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) eventually asked for an investigation into Livingston’s death, with little result.

For additional information:

Mikkelsen, Vincent. “Coming from Battle to Face a War: The Lynching of Black Soldiers in the World War I Era.” PhD diss., Florida State University, 2007.

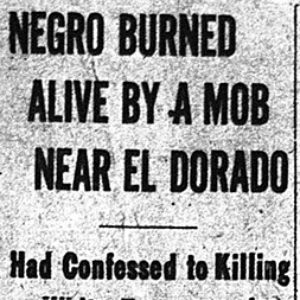

“Negro Burned Alive by a Mob near El Dorado.” Arkansas Gazette, May 22, 1919, p. 1.

Williams, Chad Louis. Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Livingston Lynching Article

Livingston Lynching Article  Union County Lynching

Union County Lynching

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.