calsfoundation@cals.org

Henry Phillips (Lynching of)

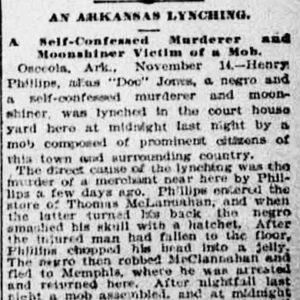

On November 13, 1897, Henry Phillips was lynched in Osceola (Mississippi County) for the alleged murder of storekeeper Tom McClanahan. Editor Leon Roussan’s coverage of the incident in the Osceola Times sparked a feud with Sheriff Charles Bowen. Bowen, a former captain in the Confederate army and a local Ku Klux Klan (KKK) leader, was prominently involved in the Black Hawk War of 1872.

According to the Osceola Times, on November 6, Tom McClanahan was brutally murdered in his store. McClanahan had come from Tennessee three years earlier to work in a local sawmill. When the mill was sold, he remained in Mississippi County to settle up outstanding claims. At the same time, he operated a small grocery store in his tenant house on the Odom place, four miles south of Osceola. Late on the night of Saturday, November 6, someone allegedly entered his store asking for quinine. When he turned his back to get the medicine, the customer hit him over the head repeatedly with a hand axe. The coroner’s jury could find no substantial evidence of who committed the crime.

There were, however, some clues. An African American who had been to the store earlier reported seeing a “tall mulatto man” walking away from the premises. Yet another black witness, who had picked up some of McClanahan’s freight from the landing, attempted to deliver it early Sunday morning and could not get McClanahan to answer. Shoppers who came to the store later that morning found the door open and discovered the body. McClanahan’s gold watch and other valuables were missing.

The “mulatto man” seen at the store, who had been picking cotton for Tom Shedden, was missing that Sunday morning, and someone matching his description had boarded the Robert E. Lee at Butler’s landing on the Mississippi River around midnight. While he was on the boat, he left some money with Clerk Smithers, and he left a pistol and gold watch with the barkeeper on deck.

John A. Lovewell, the former sheriff of Mississippi County, took the boat to Memphis, Tennessee, on Tuesday, and with the help of the Memphis police, captured Henry Phillips, who apparently went by the name of Jones or Jackson in Memphis. He was put in jail in Memphis. The chief of police there offered to keep Phillips safe in jail until the circuit court convened, but his offer was refused. Phillips was brought back to Osceola, greeted by only a small crowd at the landing and peacefully put in the county jail. However, tempers began to rise, and a group of twenty to thirty “youngsters” gathered in front of the courthouse demanding justice. Lovewell managed to dissuade them and sent them home. In the meantime, several prominent citizens offered to provide additional security for the prisoner but were told that the jail was secure and there was no danger of a lynching.

Around midnight on November 13, the mayor of Luxora (Mississippi County) and the business manager of the opera house there appeared with thirty or forty men and lynched Phillips. According to the Houston Daily Post, “Phillips made a full confession. Not a shot was fired, and the mob dispersed in a quiet and orderly manner.” On December 4, the Osceola Times, quoting the Mississippi County Democrat, explained the participation of the men from Luxora. The article said that McClanahan was from Union City, Tennessee, and many of the mill workers around Luxora knew him and his family and respected him. He was always “ready to assist or befriend any one from that section, and his horrible death at the hands of a brutal assassin exasperated them beyond expression, as each felt that he had lost a personal friend.”

The lynching infuriated Leon Roussan, the editor of the Osceola Times and longtime resident of Mississippi County. In the November 20 issue of the Times, Roussan claimed that Sheriff Charles Bowen had announced publicly that Phillips would be lynched and that reports of his statements had run in the Memphis newspapers. Roussan was outraged: “When we see those who are our friends and whom the people at large have elevated to positions of honor and trust…fall short and fail in the discharge of a public duty, we feel like throwing away our pencil and bowing our head in shame and pitying silence….What do we pay taxes for and build Court-houses and jails and elect officers to carry out and execute the laws? Surely not to engender and fester the mob spirit in our free American land, where every man is deemed innocent until declared guilty by a jury of his peers….He deserved death…but the manner of his death, and the seed sown to his grave will sprout and bear a crop that will lash and harry generations to come.”

By November 26, Roussan had been forced to flee the county to “avoid a personal difficulty with the Sheriff.” He left behind an article that his wife, Adah, published in the Times on December 4. Sheriff Bowen had apparently approached Roussan to tell him that his comments in the paper had “done him a great injustice.” Roussan responded that he had gathered his information from a variety of sources, and that if Bowen could point out any inaccuracies, he would be happy to correct them and apologize. Bowen at first promised to do so but, later in the day, approached Roussan, cursed him, and assaulted him. Roussan again asked him to state his grievances so that they might be corrected. When Bowen had not responded by November 24, Roussan sent a note to Bowen via Captain S. S. Semmes (a local lawyer and former county judge) again asking Bowen to state his grievances.

The next day, Colonel J. T. Lasley delivered a retraction to Roussan and demanded that it be “published just as it was, and without explanation or comment as the only condition of an amicable settlement.” This retraction read in part: “In the last issue of the TIMES, appeared an editorial reflecting in the strongest terms upon Sheriff Bowen and the mayor of Luxora…based upon numerous statements published in the Memphis papers, which we supposed at the time to be true, but subsequently found were unqualifiedly false…calculated not only to work a great injury to the gentlemen referred to but to the community at large. In the hope that this retraction may undo the evil referred to, so far as lies within my power, I here submit it and trust the papers which reproduced my editorial may give this the same publicity.”

Roussan refused to publish the retraction, saying that it required him, “under penalty of death, to brand myself as an unmitigated liar. This I most emphatically decline to do….This article [will] in all probability, end my editorial connection with the TIMES as I am not willing to be subjected to the dictation of an arbitrary power which invests autocratic power in one man to become censor of the press and arbiter of my fate.” Adah Roussan declined to publish her husband’s article in the November 27 issue of the Times, hoping that “Mr. Bowen’s friends might realize what he had done, in trying to compel a truthful man to dishonor himself; as well as the outrage to the constitutional rights guaranteed in the liberty of the press, and the freedom of speech.”

According to the New York Sun, Governor Daniel Webster Jones had been informed of the situation and advised Circuit Judge F. G. Taylor to “see that no bulldozing tactics are practiced in his jurisdiction by any county official.”

On December 18, it was reported in the Times that the Mississippi County grand jury had not investigated the lynching. Judge Taylor offered only to answer questions on the law in the case “as some of them had stood by consenting to this outrage upon their county, and knew who composed the mob.” No questions were asked. As for the assault by Bowen on Roussan, as no one could be found who heard Bowen’s threat to murder Roussan, it was “passed over as of little consequence. As actions speak louder than words, their approval of their sheriff is unqualified.”

Roussan did, in the end, find it necessary to leave the county for about a year; his name disappeared from the masthead of the Times, and his wife mentioned several times in editorials that he was living in Memphis. As of the 1900 census, he was living in Osceola with his wife and a nephew, Euclid Randle. He was working as an editor, and Adah was employed as a schoolteacher. Tempers must have cooled, since Charles Bowen remained in Mississippi County until his death in 1907.

For additional information:

“An Arkansas Lynching.” Houston Daily Post, November 15, 1897, p. 5.

“Fled from a Murderous Sheriff.” The Sun (New York), December 7, 1897, p. 1.

“Murder Most Foul.” Osceola Times, November 13, 1897, p. 4.

“To the People of Mississippi County.” Osceola Times, December 4, 1897, p. 4.

“Strung Up, According to Programme.” Osceola Times, November 20, 1897, p. 4.

Untitled. Osceola Times, December 18, 1897, p. 1.

Whayne, Jeannie. Delta Empire: Lee Wilson and the Transformation of Agriculture in the New South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Mississippi County Lynching

Mississippi County Lynching  Phillips Lynching Article

Phillips Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.