calsfoundation@cals.org

Acanthocephalans

aka: Spiny-Headed Worms

aka: Thorny-Headed Worms

These cylindrical metazoan worms, superficially similar to nematodes, belong to the phylum Acanthocephala and include four classes, ten orders, twenty-six families, and about 1,300 species. Recent molecular studies suggest that Rotifera (rotifers) and Acanthocephala are phylogenetically related sister groups. Adult members are highly specialized, dioecious (having distinct male and female colonies, as opposed to hermaphroditic) parasites of the intestinal tract of a variety of vertebrates (but not generally humans). They cause serious disease fairly rarely. The life cycle involves at least two hosts, either an aquatic intermediate host (Amphipoda, Copepoda, Isopoda, and Ostracoda) or terrestrial intermediate hosts including insects, crustaceans, and myriapods. Fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals serve as definitive hosts. Acanthocephalans range from 0.92 to 2.4 millimeters long in Octospiniferoides chandleri from the gulf killifish (Fundulus grandis) on the Texas coast to over a meter in length in Oligacanthorhynchus longissimus from aardvarks. While acanthocephalans do occur in Arkansas, they pose little health concern to people.

The first to provide a description of an acanthocephalan was the Italian physician Francisco Redi (1626–1697), who, in 1684, reported white worms with hooked, retractable proboscides in the intestines of eels, Anguilla sp. In 1802, Karl Asmund Rudolphi (1771–1832), the father of helminthology, was the first to name these worms Acanthocephala and give them an ordinal rank with one genus, Echinorhynchus. Others followed, and this genus was divided into several genera, thereby beginning the modern classification of the Acanthocephala.

The body of an acanthocephalan is made up of two major parts: the presoma and the metasoma, all covered by a tegument. The presoma contains the acanthocephalan’s distinguishing feature: a retractable and inversible proboscis armed with rows of recurved hooks. The tube-shaped metasoma is the rest of a solid body mainly containing male or female sexual organs.

Acanthocephalans usually exhibit some degree of sexual dimorphism in size, with females being larger. In males, two testes usually occur in most species, and their location and size are somewhat constant for each species; however, one testis occurs in those of the family Fessisentidae. Several accessory glands are also present, the most noticeable of which are the cement glands that secrete a copulatory cement of tanned protein. The cement serves to plug the female’s vagina after sperm transfer from a small penis in the male, and it rapidly hardens to form a copulatory cap. Another male accessory sex organ is the copulatory bursa, which contains a muscular sac called Saefftigen’s pouch. When this contracts, fluid is forced into the lacunar system of the bursa, and it is everted by hydrostatic pressure.

The female worm contains an ovary that fragments into ovarian balls. These balls of oogonia float freely within the ligament sac, and the posterior end of this sac is attached to a muscular uterine bell. The uterine bell permits mature eggs to pass into the uterus and vagina and out the genital pore, while returning immature eggs to the ligament sac. At this point in most species, the ligament sac has disintegrated. From a single copulation with a male acanthocephalan, the female releases thousands or even millions of embryonated eggs, and these pass from the definitive host in the host’s feces. However, male acanthocephalans tend to mate indiscriminately and often.

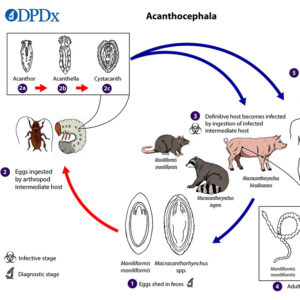

In the life cycle, after an appropriate intermediate host has ingested an egg, the egg matures into a larva (acanthor) that moves out of the host’s stomach into the body cavity to continue its maturation into a cystacanth when encysted. The eggs of some species can withstand temperature ranges of -10°C to 45°C and remain infectious for up to three years in the soil. Once the intermediate host is eaten by the definitive host, the adult worms establish, mature, and reproduce in the small intestine.

In some instances, infection with acanthocephalans may alter the behavior of the intermediate host, presumably making it more prone to predation by the vertebrate definitive host. For example, cockroaches infected with cystacanths of the common rat acanthocephalan (Moniliformis moniliformis) have been demonstrated to exhibit delayed response time and to spend more time exposed on light-colored surfaces.

Pomphorhynchus bulbocolli is widely distributed in North American freshwater fishes and has been reported from more than eighty hosts. Intermediate hosts include amphipods (Hyalella azteca) and isopods (Caecidotea and Gammarus). This acanthocephalan was recently reported from a midland watersnake (Nerodia sipedon pleuralis) in Independence County. The presence of P. bulbocolli in this snake is considered to be an artifact of a piscivorous diet, and the host should be considered accidental. However, this would be the first time this acanthocephalan has been reported from Arkansas.

Plagiorhynchus cylindraceus is a common acanthocephalan of robins (Turdus migratorius) and other passerine birds of North America. When eggs are eaten by a terrestrial isopod (Armadillidium vulgare), the acanthor develops, and cystacanths are not infective to the definitive host until about two months later. Once a suitable bird ingests the infected isopod, the cystacanth’s proboscis evaginates, pierces the cyst, and attaches to the host gut wall, where the worm develops into the adult. In addition, P. cylindraceus causes pillbugs (and other isopods) to reside more commonly in exposed areas and become more susceptible to being eaten by starlings. Interestingly, encapsulated P. cylindraceus has been found in the mesenteries of a mammalian insectivore (shrew), which would serve only as a paratenic (rather than definitive) host and stop the parasite from developing further in the life cycle.

Corynosoma constrictum was described in 1892 from the American scoter, Oidemia americana, in Yellowstone Lake, Wyoming. It has since been reported from various species of ducks in inland and coastal North American locations. Duck hunters in Arkansas may come in contact with this acanthocephalan, as it infects many duck species, including mallards, pintails, shovelers, teals, and wigeons migrating through the state.

As a cosmopolitan parasite of swine, Macracanthorhychus hirudinaceus has been known since the mid-1800s. Interestingly, this parasite was reported from a child in the Czech Republic in 1859. This type of infection in humans was relatively common in Russia, where children ingested the intermediate hosts (beetle larvae). In the life cycle, eggs are eaten by white grubs (larvae) of the beetle family Scarabaeidae, and they hatch in the midgut, penetrate the lining, and develop into acanthellas. Cystacanths then develop and are infective to definitive hosts. The usual definitive host (pigs) become infected when they eat grubs or adult beetles. In addition, there is a report of the raccoon acanthocephalan (Macracanthorhynchus ingens) infecting children in Texas who presumably became infected by eating the infected beetle intermediate host.

Generally speaking, acanthocephalans do not pose much of a medical threat to human health. The earliest known infection in a human with an acanthocephalan was from M. moniliformis eggs (normally from rats, cats, dogs, and red foxes) found in Utah in the fecal coprolite of a prehistoric man. In 1888, an Italian man named S. Calandruccio infected himself by ingesting larvae of M. moniliformis and reported gastrointestinal distress; he shed the eggs in two weeks. This served as the first report of how the infection manifested in a human. Cases of human infection by M. moniliformis have been reported in the United States, Iran, Iraq, and Nigeria.

One acanthocephalan that occurs in fishes of Arkansas and at least twenty other U.S. states is Neoechinorhynchus cylindratus. It has been reported from piscivorous game fishes, including largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) and bluegills (Lepomis macrochirus) from the state. At least seven species of ostracods can serve as the first intermediate host, with smaller non-game fishes as second intermediate hosts.

Acanthocephalans from Arkansas amphibians include Fessisentis vancleavei, which has been reported from Oklahoma salamanders (Eurycea tynerensis) from Franklin and Johnson counties; it has also been reported in Cleburne County. In addition, an unknown species of oligacanthorhynchid cystacanth was reported from a western slimy salamander (Plethodon albagula) from Stone County and a many-ribbed salamander (Eurycea multiplicata) from Petit Jean State Park in Conway County.

A complex of Neoechinorhynchus species infects aquatic turtles, and several have been reported from Arkansas, including N. chrysemydis, N. emydis, N. emyditoides, and N. pseudemydis. These are usually found in great numbers in the intestinal tract of various emydid turtles, including those in the genera Chrysemys, Graptemys, Pseudemys, and Trachemys. Indeed, photographs of N. emydis from a common map turtle (Graptemys geographica) from Marion County are shown on the cover of the 2014 issue of the Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science.

Little is known about the acanthocephalans infecting Arkansas birds. However, Centrorhynchus conspectus has been reported from great horned owls (Bubo virginianus) in Benton and Madison counties.

In Arkansas mammals, severe moniliformis caused by Moniliformis clarkii has been reported in a gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) from Arkansas County, and M. ingens has been reported in raccoons (Procyon lotor) from Drew and Van Buren counties. Opossums (Didelphis virginiana) have been common hosts of acanthocephalans, including Centrorhynchus conspectus and Oligacanthorhynchus microcephalus and Plagiorhynchus cylindraceus from Van Buren, Washington, and Yell counties.

For additional information:

Amin, Omar M. “Classification of the Acanthocephala.” Folia Parasitologica 60 (2013): 273–305.

Bethel, William M., and John C. Holmes. “Altered Evasive Behavior and Responses to Light in Amphipods Harboring Acanthocephalan Cystacanths.” Journal of Parasitology 59 (1973): 945–956.

Buckner, Richard L., and Brent B. Nickol. “Redescription of Fessisentis vancleavei (Hughes and Moore, 1943) Nickol, 1972 (Acanthocephala: Fessisentidae).” Journal of Parasitology 64 (1978): 635–637.

Cloutman, Donald G. “Parasite Community Structure of Largemouth Bass, Warmouth and Bluegill in Lake Fort Smith, Arkansas.” Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 104 (1975): 277–283.

Crompton, David W. T., and Brent B. Nickol. Biology of the Acanthocephala. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Dingley, D., and Paul C. Beaver. “Macroacanthorhychus ingens from a Child in Texas.” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 34 (1985): 918–920.

Ellis, R. D., O. J. Pung, and Dennis J. Richardson. “Site Selection by Intestinal Helminths of the Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana).” Journal of Parasitology 85 (1999): 1–5.

Goater, Timothy M., Cameron P. Goater, and Gerald W. Esch. Parasitism: The Diversity and Ecology of Animal Parasites. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Marquardt, William C., Richard S. Demaree, and Robert B. Grieve. Parasitology and Vector Biology. 2nd ed. San Diego: Harcourt Academic Press, 2000.

McAllister, Chris, and Omar Amin. “Acanthocephalan Parasites (Echinorhynchida: Heteracanthocephalidae; Pomphorhynchidae) from the Pirate Perch (Percopsiformes: Aphredoderidae), from the Caddo River, Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 62 (2008): 151–152. Online at http://libinfo.uark.edu/aas/issues/2008v62/v62a24.pdf (accessed November 23, 2020).

McAllister, Chris T., Charles R. Bursey, Henry W. Robison, David A. Neely, Matthew B. Connior, and Michael A. Barger. “Miscellaneous Fish Helminth Parasite (Trematoda, Cestoidea, Nematoda, Acanthocephala) Records from Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 68 (2014): 78–86. http://libinfo.uark.edu/aas/issues/2014v68/v68a12.pdf (accessed November 23, 2020).

McAllister, Chris T., Charles R. Bursey, Henry W. Robison, and Michael A. Barger. “Haemogregarina sp. (Apicomplexa: Haemogregarinidae), Telorchis attenuata (Digenea: Telorchiidae) and Neoechinorhynchus emydis (Acanthocephala: Neoechinorhyncidae) from Map Turtles (Graptemys spp.), in Northcentral Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 68 (2014): 154–157. http://libinfo.uark.edu/aas/issues/2014v68/v68a26.pdf (accessed November 23, 2020).

McAllister, Chris T., Matthew B. Connior, Charles R. Bursey, and Henry W. Robison. “A Comparative Study of Helminth Parasites of the Many-Ribbed Salamander, Eurycea multiplicata and Oklahoma Salamander, Eurycea tynerensis (Caudata: Plethodontidae), from Arkansas and Oklahoma.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 68 (2014): 87–96. http://libinfo.uark.edu/aas/issues/2014v68/v68a13.pdf (accessed November 23, 2020).

McAllister, Chris T., Stanley E. Trauth, and Charles R. Bursey. “Metazoan Parasites of the Graybelly Salamander, Eurycea multiplicata griseogaster (Caudata: Plethodontidae), from Arkansas.” Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 62 (1995): 66–69.

McAllister, Chris T., Steve J. Upton, and Stanley E. Trauth. “Endoparasites of Western Slimy Salamanders, Plethodon albagula (Caudata: Plethodontidae), from Arkansas.” Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 60 (1993): 124–126.

Moore, Janice. “Altered Behavior in Cockroaches (Periplaneta americana) Infected with an Archiacanthocephalan Moniliformis moniliformis.” Journal of Parasitology 69 (1983): 1174–1177.

Moore, Janice G., G. F. Fry, and E. J. R. Englert. “Thorny-Headed Worm Infection in North American Prehistoric Man.” Science (1969): 1324–1325.

Nickol, Brent B. “Phylum Acanthocephala.” In Fish Diseases and Disorders I. Edited by Patrick T. K. Woo. Wallingford, UK: CAB International, 1996.

Petrochenko, V. I. Acanthocephala of Domestic and Wild Animals, Vols. 1 and 2. Israel Program for Scientific Translations. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR, 1971.

Richardson, Dennis J. “Acanthocephala of the Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana) in Arkansas, with a Note on the Life History of Centrorhynchus wardae (Centrorhynchidae).” Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 60 (1993): 128–130.

Richardson, Dennis J. “Acanthocephala of the Raccoon (Procyon lotor) with a Faunal Review of Macracanthorhynchus ingens (Acanthocephala: Oligacanthorhynchidae).” Comparative Parasitology 81 (2014): 44–52.

Richardson, Dennis J., and Adel Abdo. “Postcyclic Transmission of Leptorhynchoides thecatus and Neoechinorhynchus cylindratus (Acanthocephala) to Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides).” Comparative Parasitology 78 (2011): 233–235.

Richardson, Dennis J., and Michael A. Barger. “Microhabitat Specificity of Macracanthorhynchus ingens (Acanthocephala: Oligacanthorhynchidae) in the Raccoon (Procyon lotor).” Comparative Parasitology 72 (2005): 173–178.

Richardson, Dennis J., and Cheryl D. Brink. “Effectiveness of Various Anthelmintics in the Treatment of Moniliformiasis in Experimentally Infected Wistar Rats.” Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 11 (2011): 1151–1156.

Richardson, Dennis J., and Brent B. Nickol. “The Genus Centrorhynchus (Acanthocephala) in North America with Description of Centrorhynchus robustus n. sp., Redescription of Centrorhynchus conspectus, and a Key to Species.” Journal of Parasitology 81 (1995): 767–772.

———. “Acanthocephala.” In Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds. edited by Carter T. Atkinson, N. Thomas, and D. B. Hunter. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing, 2008.

Schmidt, Gerald D. “Acanthocephalan Infections of Man, with Two New Records.” Journal of Parasitology 57 (1971): 582–584.

———. “Revision of the Class Archiacanthocephala Meyer, 1931 (Phylum Acanthocephala), with Emphasis on Oligacanthorhynchidae Southwell and MacFie, 1925.” Journal of Parasitology 58 (1972): 290–297.

Singleton, Jeural, Dennis J. Richardson, and J. Mitchell Lockhart. “Severe Moniliformiasis (Acanthocephala: Moniliformidae) in a Gray Squirrel, Sciurus carolinensis, from Arkansas, USA.” Journal of Wildlife Diseases 29 (1993): 165–168.

Yamaguti, Satyu. Systema Helminthum, Acanthocephala. Vol. 5. New York: Interscience, 1963.

Chris T. McAllister

Eastern Oklahoma State College

Science and Technology

Science and Technology Acanthocephala Life Cycle

Acanthocephala Life Cycle

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.