calsfoundation@cals.org

Pine Bluff Lynchings of 1892

On February 14, 1892, John Kelley (sometimes spelled Kelly) was lynched in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) for the murder of W. T. McAdams. At the time, Pine Bluff was the second-largest city in Arkansas. The black population in Jefferson County was seventy-three percent, and there were a number of prominent African-American landowners and merchants. The city boasted a black newspaper, as well as the state’s only college for African Americans, Branch Normal School (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff).

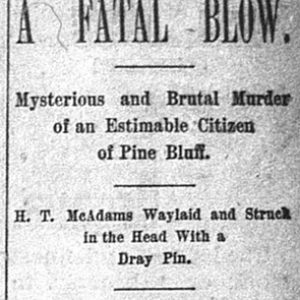

According to the Arkansas Gazette, on the night of February 9, John Kelley and several accomplices allegedly murdered W. T. McAdams, an agent for the Obest Brewing Company and a highly respected Pine Bluff citizen. At 10:30 p.m., McAdams was walking near his home when someone hit him over the head with a dray pin. He screamed, alerting his wife. He then died of his wounds. When his body was found, his pistol and a small amount of money were missing.

The authorities investigated, and, the following morning, the police arrested two black men—Gilbert Banks and a man named Smith—and two black women who had been seen in the neighborhood around the time of the murder. By the evening of February 10, officials were looking for John Kelley as the probable murderer. According to the Gazette, “If the parties obtain enough evidence to fix the murder on the parties arrested, there will be no need of a trial, as the citizens here are very indignant, and they would make an example at once of the guilty parties….The frequent murders of white men by negroes in this county of late have aroused the community to a high pitch of excitement.”

Rumors that Kelley had been captured at Altheimer (Jefferson County) proved false, and deputies started out for Helena (Phillips County), Kelley’s home, to arrest him. Gilbert Banks (sometimes called Blanks), who had been arrested as an accessory, denied any involvement in the crime but did say that he had seen Kelley the previous evening with a pistol and $5, which Kelley said he had taken from a drunken white man.

On February 14, the police chief received a telegram that Kelley had been captured at Rison (Cleveland County). Officers were sent to Rison to bring him back to Pine Bluff by train. The news spread around town, and a mob of 200 armed men met the train at 9:00 p.m.. Despite pleas from the mayor, the mob stopped the train and took the prisoner, marching him up the main street to the courthouse. By this time, the size of the mob had grown to around 1,000. While the crowd yelled, a rope was put around Kelley’s neck, and he was taken to the courthouse steps and given a chance to speak. He denied his guilt, saying that he had bought McAdams’s watch. The crowd then hanged him from a telephone pole that stood directly across from the courthouse. During this process, he allegedly confessed that he had hit McAdams but did not intend to kill him. After he was strung up, more than 100 bullets were fired at him.

Once Kelley had been hanged, the cry went up to hang Banks. Refused the keys to the jail, the mob found a telephone pole behind the courthouse and used it as a battering ram to break down the outer wall of the jail. A deputy told the members of the crowd that if they did not break into the cell, he would send to Sheriff Frank Silverman’s home for the keys. Banks was in a cell with a white man named Tom Bell. Though Bell was not involved in the McAdams case, the mob believed he was a suspect in another murder.

After the keys arrived, Banks was taken from the cell and given the opportunity to speak. He denied being with Kelley at the time of the murder. He was then hanged from the same telephone pole as Kelley, and even more shots were fired this time. (A report in the Chicago Tribune says that the accomplice hanged with Kelley was Culberth Harris, rather than Gilbert Banks; a number of other newspapers, including the Sedalia Weekly Bazoo, said the same.) According to the Lowell Journal and the Sedalia Weekly Bazoo, because it was Sunday night, large crowds of churchgoers, many of them women, were trapped downtown after church and witnessed these gruesome murders.

The crowd then turned its sights on Tom Bell, but General H. King and Major N. T. White said to the people in the crowd “that they had done good work, and that the proof was not sufficient against Bell for them to lynch him, and advised them to go home, telling them he was secure should they want him at any time.” According to the report in the Gazette, “The mob was composed of some of our best citizens, and no masks were used, and everything transpiring could be seen by the bright lights and the moon.” An additional article on same page dated February 15 stated that John Kelley “was today recognized as Ed Wilson, wanted at Brownsville, Tenn., for wife murder, committed six years ago. W. A. Morrow, a reputable citizen, late of Brownsville, who knew Wilson well, says there is no doubt that Kelley is the man. Kelley came here about four years ago and is thought to have committed several murders since.”

At least one African-American newspaper was outraged at these events. Writing in the Kansas City American Citizen, Charles H. J. Taylor described those who participated in the lynching as cowards and brutes. While he mistakenly placed the lynching in Helena instead of Pine Bluff, he declared, “This happened in a town of churches….Is there no efficacy in prayer? Shame on every man and woman who wields the least bit of influence in relation to the Arkansas state government, if you remain silent….Why should there be the least excuse for mob-law against the poor Negro in this country? The whites of Arkansas, and for that matter, of every state in the Union, control entirely the state machinery.…That a mob should be allowed in a country claiming to lead the world on religious lines to take unarmed men and hang them without any kind of trial. In the United States Senate these same whites of whom these ruffians come have been referred to as a ‘noble race,’ a ‘kingly race’; yes, indeed, such ‘nobleness’ and ‘kingly bearing’ would disgrace hell.”

For additional information:

“A Fatal Blow.” Arkansas Gazette, February 11, 1892, p. 1–2

“Expiation.” Pine Bluff Commercial, February 15, 1892, p. 3.

Taylor, Charles H. J. “Is God Dead?” Kansas City American Citizen, February 19, 1892; reproduced in Christopher Waldrep. Lynching in America. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

“Lynched in a City.” Sedalia (Missouri) Weekly Bazoo, February 23, 1892, p. 7.

“A Mob’s Victims.” Lowell (Michigan) Journal, February 17, 1892, p. 1.

“Two Brutal Murderers Lynched Sunday Night at Pine Bluff.” Arkansas Gazette, February 16, 1892, p. 1.

“Two Were Lynched.” Chicago Tribune, February 15, 1892, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Pine Bluff Lynching Article

Pine Bluff Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.