calsfoundation@cals.org

Warren (Bradley County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 33º36’45″N 092º03’52″W |

| Elevation: | 213 feet |

| Area: | 7.03 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 5,453 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | December 26, 1850 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

301 |

492 |

954 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

2,057 |

2,145 |

2,523 |

2,516 |

2,615 |

6,752 |

6,433 |

7,646 |

6,455 |

6,442 |

|

2010 |

2020 | ||||||||

|

6,003 |

5,453 |

Warren has been the Bradley County seat of justice since the county’s organization on December 18, 1840. Located in the southeastern part of the state, the town continues to be the county’s commercial, educational, and health care center. It is located on what was variously called the Chicot Trace, Gaines Landing Road, Fort Towson Road, and Washita Road.

Early Statehood through Reconstruction

Warren once served as the official center of the territory now composed of Calhoun, Cleveland, Ashley, and Drew counties. The first circuit court met on April 26, 1841, at Hugh Bradley’s house. The naming of Warren remained clouded in conjecture for a long time; according to local family tradition, the town was named for Hugh Bradley’s slave, Warren Bradley, and this was finally confirmed in 2015 with the discovery of a time capsule in the county courthouse. There is sufficient evidence, however, that the town was named for Bradley’s close friend, Edward Allen Warren, who practiced law in Camden (Ouachita County) and also served the state as a U.S. representative.

Prior to the incorporation of Warren, there was a settlement close by named Cabeens. In early years, it was also known as Saline Settlement and Pennington Settlement. Dr. John Thomas Cabeen served as postmaster from 1832 until 1843. John Harvie Marks donated thirty acres, and John Splawn donated ten acres of land for the town site.

Warren suffered more from Reconstruction than from the nearby Civil War engagements at Marks’ Mills, Mount Elba, and Longview. There was a Confederate camp located between Warren and the Saline River known as the Warren Camp. Troop movements were numerous between this camp and Camp Shanghai (later Selma) in Drew County. Dr. Junius Bragg wrote letters in which he described the hardships for Warren’s citizens because of troops confiscating all food products. When martial law was declared and Reconstruction began, the town was devoid of business life. The only store in the little hamlet was a new store that opened in May 1865 for the benefit of the Federal soldiers who garrisoned the town. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) became popular in this period, and reports of nightriders were numerous. Governor Powell Clayton sent a militia from Conway (Faulkner County) to Warren to combat the lawlessness in the area.

Post Reconstruction through Modern Era

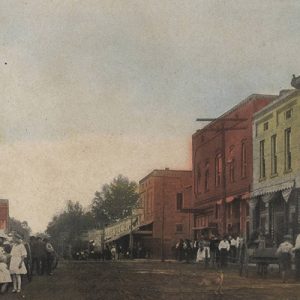

Major John C. Bratton, W. H. Wheeler, John T. Ederington, and Benjamin Martin later served as the basis for business in Warren. Merchants and Planters Bank was established in the 1890s, and a few years later in 1901, the Warren Bank was organized. These two banks are still in existence today.

On August 5, 1880, Warren became the western terminus of the Ouachita Division of the Little Rock, Mississippi River and Texas Railway. The advent of the rail opened the lucrative timber market that before suffered from isolation.

In 1887, two white men named in reports Hamilton and Ludberry were lynched for allegedly murdering a set of brothers. Two years apart, in 1890 and 1892, African American brothers William and Henry Beavers were lynched for allegedly assaulting young women. Their ages were estimated to be fourteen and sixteen. In 1903, a man named John Turner, also Black, was lynched for having allegedly “attempted assault” on a local white woman.

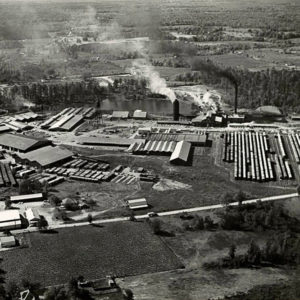

Long before the large lumber mills located in Warren, there were many small mills throughout the county. Among the early mills were Shirey & Butler; Crandall & Leavitt; Edmondson; Glasgow & Temple; Lanark Mill; Whittington; Parker & Kinard, Lowry & Taylor, and J. E. Walker’s mill. Thomas A. Carpenter established the first large lumber mill in Warren in 1891. The Weyerhaeuser group founded the Southern Lumber Company. Rittenhouse and Embree established the Arkansas Lumber Company, and a local man, William H. Wheeler, established the Bradley Lumber mill.

Because of the new mills, Warren began to grow quickly both in business and population. When registration for World War I began, the mills experienced a shortage of manpower and began hiring women. The dress rule for women was simple—wear a dress to work, change into slacks, and wear a dress home.

Two notable aspects of Warren are that it has a YMCA established in 1920, and that many of its antebellum homes still exist today. Eleven buildings in Warren are on the National Historic Register.

Warren has endured two of the most deadly tornadoes in Arkansas history. On January 3, 1949, a late-afternoon storm killed fifty-five people and injured more than 250. In one day, the funerals were so numerous that choirs took turns singing as the coffins rolled down church aisles. The destruction of the Bradley mill displaced 1,000 employees. On March 28, 1975 (Good Friday), seven people died and sixty-two were injured when a tornado took the same path as the one in 1949.

Warren’s heyday was in the 1920s and 1930s when the lumber mills were most active. Although the mills declined after years of harvesting timber, Potlatch is still one of the largest employers in Warren. Tomato farmers also employ numerous workers.

Education

The first school was established in 1847 near Cabeens and was held in the Methodist Church building. Josephine Horne opened an academy for young ladies in 1851 and charged $35 for a five-month session. Thomas Henry Mathis, a Kentuckian, organized a private school in 1856. Mathis later went on to be one of the founders of Rockport and Mathis in Texas. The Baptist church organized the Baptist Centennial Institute in 1874, and in 1906, the Presbyterians raised money to build the Presbyterian Training School, a scholarship school. Like most of the smaller schools in the state, Warren was fortunate not to have major problems during integration. The town currently has five schools: a high school, a junior high, two elementary, and the Southeast Arkansas Community Based Education Center (SEACBEC), a vocational/technical school. Warren is also home of the Southeast Arkansas Human Development Center, one of six in the state that is dedicated to providing training and care to people with developmental disabilities.

Attractions

Warren calls itself the Pink Tomato Capital of the World. It is home of the Pink Tomato Festival, one of the state’s oldest festivals, established in the 1950s. Each June, thousands of people descend on Warren for the festival. Many state dignitaries and the governor usually participate in a tomato-eating contest. One of the most enjoyable activities is the Tomato Luncheon, where the entire menu, including dessert, is made with tomatoes. In 1987, the Arkansas General Assembly officially adopted the South Arkansas Vine Ripe Pink Tomato as the state fruit. In addition, the John Wilson Martin House on Ash Street holds the Bradley County Historical Museum.

Famous Residents

One of the most prominent men from Warren in the early days was Josiah Gould, a lawyer, a circuit judge, and a state senator for several terms. In 1858, he wrote the first digest of the statutes of Arkansas; it is known as “Gould’s Digest.” Another well-known person was John Milton Bradley. He was the colonel of Company E, Ninth Arkansas, part of what was referred to as the Parsons Unit. John Lipton served as the state highway commissioner and speaker of the Arkansas House of Representatives.

For additional information:

Bradley County Centennial Magazine: Presenting the Growth and Progress of the County. Warren, AR: 1936.

Gateswood, Robert L. A Bicentennial History of Bradley County, Arkansas. N.p.: Warren and Bradley County Bicentennial Committee, 1976.

Jann Woodard

Benton, Arkansas

Arkansas Lumber Company

Arkansas Lumber Company  Arkansas Lumber Company

Arkansas Lumber Company  Bradley County Clerk

Bradley County Clerk  Bradley County Courthouse

Bradley County Courthouse  Bradley County Courthouse

Bradley County Courthouse  Bradley County Map

Bradley County Map  Southerland Hotel

Southerland Hotel  Southern Lumber Company

Southern Lumber Company  Warren Church

Warren Church  Warren Depot

Warren Depot  Warren Mill Worker Housing

Warren Mill Worker Housing  Warren Street Scene

Warren Street Scene  Warren Tornado

Warren Tornado  Warren View

Warren View

I remember picking pink tomatoes and the Campbell Soup Company carting them off. Tomato fights, tomato-eating contests, tomato stompin, tomato worms Its difficult for me to believe that kids today could have as much fun as we did back in 1957 when we were all college kids (and a few pre-college kids). My friends were the Nelsons: son Dick, father Cyrus, Mrs. Nelson, and a daughter. I can remember that Dick had a job working with the Arkansas State Police as a radio dispatcher. I was sitting in the studio reading something when Dick made an APB that there was a tornado in the immediate area. It then roared through town and dropped a railroad crosstie right in the center of the Nelsons dining-room table. I remember looking up and the sky was black with crossties, and it started raining ties all over town. Many people died from that storm. A black man named Moree was the towns designated lawnskeeper. When he would pass by, he would pull a hankie from his pocket to wipe his brow and say, Sho is hot! Jack Scobey lived across from the Nelsons and drove one of the tri-five Chevrolets. Bob Fullerton, with the Bradley County Lumber Mill, and his daughter Roberta were some of the greatest party hosts. Roberta, always an instigator, was the most fun girlfriend I ever had. I was from Little Rock, but Warren was my town in the summer. In the winter, I was struggling at Little Rock Junior College, but finally took a family friends advice and joined the navy. The friend was Sen. J. William Fulbright, and through his relations with my family, he got me pointed in the right direction. I spent thirty-four years working as a consultant in naval aerospace design engineering. I retired in 1994 in Phoenix, but Im proud to say that my friends from Warren have done well.