calsfoundation@cals.org

Lost Louisiana Mine

The Lost Louisiana Mine is an American legend about buried Spanish treasure that has been sought since the Victorian era, primarily in Arkansas’s Ouachita and Ozark mountains regions. The legend’s core narrative is that a Spanish expedition concealed a rich gold mine in the wilderness of Spain’s Luisiana colony (hence the name), and in returning to New Orleans, all but one of the party was killed by Indians. In the early twentieth century, variants of the legend attributed the treasure to either Freemasons or Sephardic Jews exiled from Spain who brought a fortune in gold and jewels with them, or a Catholic or Aztec trove brought from Spanish Mexico. Such Spanish treasure legends were once part of a deeply anti-Spanish bias in Europe and North America, referred to by historians as “The Black Legend,” which demonized Spanish empire-building.

The Lost Louisiana mine story apparently sprang from colonial reports of a mineral curiosity located in or near modern Pike County, Arkansas. Lieutenant Governor Francisco Bouligny in 1778 reported on gold diggings on the upper Little Missouri River, a tributary of the Ouachita River, which Chevalier D’Annemour reported in his 1803 Memoire on the Ouachita district as having been long abandoned due to either “suffocating vapors” or Indian harassment. William Dunbar in 1804 noted that pyrites (“fool’s gold”) found on the Little Missouri River had been mistaken by hunters for gold. Confusion between the homophones “Ouachita River” and “Washita River” led to the legend’s eventual extension to the Wichita Mountains of south-central Oklahoma.

Today’s Lost Louisiana Mine story can be traced to nineteenth-century stock promotions in Arkansas’s Ouachita Mountains. Following the construction of “Diamond Jo” Reynolds’s Hot Springs Railroad, enthusiastic boosterism and lavish national newspaper coverage lured midwestern capitalists to speculate in mines near Hot Springs (Garland County). The legend emerged from the Silver City (Montgomery County) mining boom of 1876–1882, and the term “Lost Louisiana Mine” was first published in the Arkansas Mining Journal of Mount Ida (Montgomery County) in 1880. The article’s reference to an 1803 French report on mines between the Ouachita and Little Missouri rivers seemingly links the legend to D’Annemour’s Memoire. Pulp-fiction writer James W. Buel helped spread the story through his book The Legends of the Ozarks (1880).

The 1882–1888 mining frenzy at nearby Bear (Garland County) popularized the story nationally. In 1886, the owners of an extinct hot spring near Bear announced it as the fabulous lost mine and sold stock in the Lost Louisiana Mining Company. Frenzied investment in the district was propelled in part by crooked mineralogists and assayers, including the Reverend Samuel Aughey, a “first-class charlatan” and disgraced professor, and Anson C. Tichenor, an imposter mineralogist who bilked investors in several western states. An independent investigation of mineral claims in the Ouachita Mountains, conducted by the Arkansas Geological Survey and released in 1888, exposed the Lost Louisiana and many other mines as fraudulent.

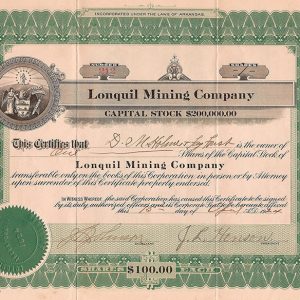

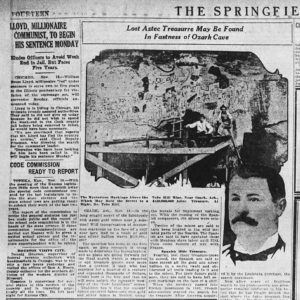

By 1900, the search for the Lost Louisiana Mine had expanded to the Ozark Mountains. Reports of Mexican mining parties periodically camping near the Mulberry River in the Boston Mountains circulated as early as the 1830s and inspired Friedrich Gerstäcker’s 1844 adventure story Die Silbermine in den Ozarkgebirgen in Nordamerica. In the 1890s, an elderly stranger calling himself Antonio Montez, who said he had been sent by President Porfirio Díaz of Mexico with treasure maps, located curious hieroglyphics on a Mulberry River bluff near Cass (Franklin County). In 1905, Dr. Lorenzo G. Hill (1861–1926) of Mulberry began purchasing land and initiated an obsessive, two-decade treasure hunt. Newspapers reported in 1907 that an extensive panel of Native American, Spanish, and Masonic hieroglyphics (petroglyphs) carved on the sandstone bluff presented clues to an $80 million Masonic treasure called the Lost Louisiana Mine. Subsequent newspaper accounts described it as a Catholic treasure with gem-encrusted gold platters, a gold Madonna, and Aztec gold valued at $110 million. Hill’s excavations were periodically directed by Charlie Gonzales, purportedly a Spaniard with secret knowledge but who was eventually ousted as a fraud. To fund excavations, the Lost Louisiana Mining and Development Company of Poteau, Oklahoma, was chartered in 1908, and the Lonquil Mining Company of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) was chartered in 1909. Arkansas’s 1915 “blue sky” law, enacted to safeguard investors from fraud, brought to a close an era of reckless speculation in Arkansas mining stocks. Hill’s death in 1926, following his arrest for selling narcotics, ended a two-decade obsession that had cost Hill $100,000.

The Lost Louisiana Mine ranks among the nation’s most popular buried treasure stories. In literature, the legend has inspired Jonathan Kellogg’s historical romance The Lost Louisiana (1900) and the novel Beneath the Stone (1918); Virgil Baker’s 1938 play Spanish Diggin’s; Lois Snelling’s novel for teenagers The Yellow Cup Mystery (1963); and Jim Carroll’s supernatural fantasy Angel Vision (1992).

For additional information:

“Arkansas Silver Mines.” Arkansas Gazette, January 2, 1881, p. 2.

Buel, J. W. Legends of the Ozarks. St. Louis: W. S. Bryan, 1880.

Bywaters, Jerry. “Buried Rubies that Have Claimed Lives.” Dallas Morning News, September 8, 1929, Feature Section, p. 4.

Comstock, Theo B. “A Preliminary Examination of the Geology of Western-Central Arkansas, with Especial Reference to Gold and Silver.” In Arkansas Geological Survey Annual Report for 1888, Vol. I, Part 2. Little Rock: Geological survey of Arkansas, 1888.

“Death Halts Long Efforts to Find Gold.” Southwest American (Fort Smith, Arkansas), May 18, 1926, p. 12.

“Gigantic Frauds.” Arkansas Gazette, August 9, 1888, p. 1.

Kennedy, Steele T. “Is There Gold Near Cass?” Arkansas Democrat Magazine, July 20, 1958, p. 8.

“May Have Found Long Lost Mine.” Arkansas Gazette, November 4, 1907, p. 2.

Plazak, Dan. A Hole in the Ground with a Liar at the Top: Fraud and Deceit in the Golden Age of American Mining. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2006.

“Seeks Wealth of Spanish Masons.” Arkansas Gazette, October 24, 1909, p. 4.

“Still Seeking Fabled Spanish Treasure in the Ozark Hills.” Ogden Standard-Examiner (Ogden City, Utah), August 21, 1927, Comic Section, p. 3.

Robert A. Myers

St. Louis, Missouri

Folklore and Folklife

Folklore and Folklife Lonquil Stock Certificate

Lonquil Stock Certificate  Lost Louisiana Mine

Lost Louisiana Mine  Lost Louisiana Mine Article

Lost Louisiana Mine Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.