calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkadelphia (Clark County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34°07’15″N 093°03’13″W |

| Elevation: | 250 feet |

| Area: | 7.54 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 10,380 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporated: | January 6, 1857 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

248 |

817 |

948 |

1,506 |

2,455 |

2,739 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

2,745 |

3,311 |

3,380 |

5,078 |

6,819 |

8,069 |

9,841 |

10,005 |

10,014 |

10,912 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10,714 |

10,380 |

Serving as Clark County’s seat of government since 1842, Arkadelphia has served as a farm market and trading center thanks to reliable water-, then rail-, then automotive-borne transportation from its perch adjacent to the Ouachita River at the edge of the Ouachita Mountains. It has a history of light industry, covering the gamut from salt extraction to lumber and aluminum, as well as recreational opportunities afforded by the nearby Ouachita and Caddo rivers and the Caddo’s impoundment, DeGray Lake. Arkadelphia’s greatest asset has been an enduring commitment to education that began with general private and denominational efforts, as well as the Arkansas School for the Blind prior to the Civil War, and blossomed with public education, a business college, and denominational colleges for Black and white Arkansans in the 1880s and 1890s. Of the five colleges founded in Arkadelphia in the decade between 1885 and 1895, two (Henderson State University and Ouachita Baptist University) continue to operate in town while two more (Shorter College and Draughon’s Business College), like the Arkansas Institute for the Blind, moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County).

Pre-European Exploration

Where Arkadelphia now stands was land which Archaic hunter-gatherers and Woodland and Mississippian cultivators traversed. The last local exemplars of Mississippian culture, the Caddo (who gave their name to the river that flows about five miles to the town’s north and to the valley through which it travels on its way to join the Ouachita), left the region about 1700. Locals have long held that Hernando de Soto brought his men along the Ouachita and camped just north of the present town site on the high bluff to which long custom has attached his name; however, scholarly reconstructions of the path of the de Soto expedition counter this claim. There are likely 100 prehistoric Indian sites within a five-mile radius of Arkadelphia, including many mounds from which citizens dug artifacts in the first half of the twentieth century.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

On a bluff overlooking the Ouachita River from the west, Adam Blakeley built a blacksmith shop and home in 1808. A few years later, a salt works (which some call Arkansas Territory’s first industry) was operating across the river, and a trading post stood near the boat landing. A decade later, Blakeleytown was thriving. At the end of the 1830s, the first lots were plotted, and Blakeleytown became Arkadelphia. The name’s originator and precise date of origin are lost; later accounts agree that early settler James Trigg reported, without attribution, that when Arkadelphia became the county seat and thus needed a more dignified name, locals combined two Greek words for “arc of brotherhood” and changed the third letter. However, many settlers came from Alabama and perhaps borrowed the name of Arkadelphia from a town north of Birmingham.

In 1842, Arkadelphia became the Clark County seat, and a brick courthouse and jail were completed in 1844. Incorporation was initiated in 1846, though it languished for a decade. In 1850, the first official census counted 162 whites and eighty-six slaves. By that point, the town included a saloon, the Arkadelphia Male and Female Institute, Methodist and Baptist churches, and a newspaper, The Sentinel. A decade later, this town, which served as the market for the surrounding river floodplain farms as well as those smaller upland ones, had the state’s seventh largest population.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

During the Civil War, Arkadelphia supplied at least two companies of troops (the militia became Company E, and the newly formed Clark County Volunteers became Company B, First Arkansas Infantry) and served as a medicinal and munitions depot, source of salt, and ordnance works. Arkadelphian Harris Flanagin became the state’s wartime governor and briefly operated from the town, but local educational and religious institutions suspended operation during the war. Engagements to its west and south briefly threatened the town when Union general Frederick Steele marched on Camden (Ouachita County), and locals sometimes faced off with deserters and draft evaders. On April 1–2, 1864 the Skirmish at Arkadelphia ended in a Union victory.

After the war, the railroad and education changed Arkadelphia. The Cairo and Fulton railroad line, following the Military Road (Southwest Trail), joined Arkadelphia and Little Rock for the first time in 1873. Once the railroad appeared, short-line spurs spread out into the surrounding pine forests and promoted the growth of sawmilling just across the river in what was briefly called Daleville (Clark County), as well as in “sawmill towns” like Graysonia (Clark County) at a greater remove from Arkadelphia. Since the railroad touched the river at Arkadelphia, the town became even more of a transportation nexus and, therefore, a farm market and trading center.

Good transportation and education-minded community leadership encouraged another kind of growth in Arkadelphia. Pre–Civil War education was private and limited to white people. In 1859, the Arkansas General Assembly incorporated the Arkansas Institute for the Blind, which remained in Arkadelphia until 1868. After the legislature created the first statewide common school system in 1866, Arkadelphians designed a city-wide segregated system, which became operational in 1871 and coexisted with private schools.

Mary Connelly, originally from the east coast, moved to Arkadelphia in 1866 and began teaching. Within three years she had purchased the Arkadelphia Male and Female Institute and ran it as the Arkadelphia Female Academy until 1874, when it closed.

Arkadelphia became an educational center with the opening of two colleges for white people (Ouachita Baptist College in 1886 and Arkadelphia Methodist College in 1890), two schools for African Americans (Bethel College, AME, in 1891 and the Colored Presbyterian Industrial School in 1896), and the first of a series of business colleges (Draughon’s in 1891). In addition to these, an elementary and secondary school for black students, called the Arkadelphia Presbyterian Academy, was founded in 1882. The Arkadelphia Baptist Academy opened in 1890, later updating its name and becoming associated with Arkansas Baptist College in Little Rock in 1892. This activity by education-minded citizens led one local newspaper to refer to the community consistently as “The City of Colleges,” while other locals called it “The Athens of Arkansas.”

In December 1877, an African-American man named Wash Atkinson was lynched in Arkadelphia for allegedly attacking a white man named H. G. Ridgeway. The mob was incensed by the news that Ridgeway might not survive his injuries, though he did.

In January 1879, Ben Daniels and two of his sons were lynched in Arkadelphia after being arrested on suspicion of robbery and assault. Armed men overpowered the guards of the Arkadelphia jail and hanged the men from a tree.

Beginning with their first game in 1895 and continuing into present day, Henderson State University and Ouachita Baptist University have maintained a friendly football rivalry, called the Battle of the Ravine because the two schools are positioned across from one another on either side of U.S. Highway 67.

Between the mid-1880s and the early 1900s, Arkadelphia acquired public utilities and facilities. In 1891, a public telephone line system, a standpipe, and water mains were introduced. Wilson (soon named Arkadelphia) Water and Light Company provided electricity. Baseball games, first played in Arkadelphia in 1874, took place after 1887 in a grand, 500-seat ballpark. The Arkadelphia Bottling Company provided portable versions of fountain drinks. A cotton mill and Elk Horn Bank opened in 1884, and Citizens National Bank opened in 1888. By the era’s end, the community was a farm market and trading center for the surrounding area, an educational center, and even more of a center for light industry, both extractive and manufacturing, as lumber, textile, and flour milling replaced salt production, while gunsmithing remained. At the turn of the century, Arkadelphia was home to one of the state’s largest lumber mills (Arkadelphia Lumber Company at Daleville), as well as one of its first successful large industries, the Arkadelphia Milling Company, which produced flour, meal, stock feed, and staves on an around-the-clock schedule.

Early Twentieth Century

The town grew little between 1900 and 1930, but a natural gas pipeline was completed in 1911, and the fledgling Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L), which initially connected Arkadelphia and Malvern (Hot Spring County), took over the local system in 1914. The Arkadelphia Confederate Monument was erected in 1911. Except for Ouachita Baptist College and Arkadelphia Methodist College, Arkadelphia’s colleges moved to Little Rock or closed because of debt. The state of Arkansas took over what had been Arkadelphia Methodist College (then named Henderson-Brown College) in 1929, changing the name to Henderson State Teachers College. U.S. Highway 67 brought with it service stations and motels (including a municipal camping facility for a brief time in the 1920s), and Arkadelphia had a pasture acting as its airport by 1918. Between the public schools and the colleges, education rivaled wood products as the area’s largest employer, while agriculture lagged behind.

The Daily Siftings Herald, a newspaper based in Arkadelphia that served Clark County and nearby portions of Hot Spring County, began operations in 1920 after two newspapers consolidated.

World War II through the Faubus Era

After the Depression, apparel manufacturers brought Hollywood Maxwell to town in 1941 and Oberman Manufacturing Company in 1945. In 1953, Reynolds Metals Company opened its Patterson aluminum reduction plant just south of Arkadelphia. In 1955, thanks to the newly formed Arkadelphia Industrial Development Commission, Tectum Corporation sited a composite-board facility on the floodplain south of town. The town’s growth after 1950 was largely because local developers opened the first significant planned housing development farther west of what had traditionally been known as West End, as well as interest in industry evidenced by the Chamber of Commerce and the Clark County Industrial Commission (now Council). Except for the drain of people into the military services and their replacement by Training Detachments at Ouachita Baptist and Henderson State colleges, the effect of World War II on the community came mainly after the war’s end. Although government war contracts touched few Arkadelphians directly, available money after the Depression whetted appetites for a lifestyle previously unknown, and experiences in the larger world encouraged locals to forsake rural living, enlarging the town at the expense of county farms in the post-war years.

Interstate 30, parallel to U.S. Highway 67, was completed in the late 1960s, dooming the small independent overnight cottages that had thrived along the highway and drawing Arkadelphia westward toward it. Six years of work on DeGray Dam ended in 1968, though its power-generation facility was not dedicated until 1972. Ouachita Baptist College became a university in 1965 and enjoyed a record enrollment the next year. The state opened the Arkadelphia unit of its Arkansas Children’s Colony for developmentally disabled children in 1968. Easier transportation and growth of Arkansas’s recreation industry attracted Alumacraft and encouraged the founding of Ouachita Marine in the mid-1960s, both to manufacture boats (Alumacraft announced its closure in 2020, however). One of the biggest factors in Arkadelphia’s growth, planning, and quality of life, the local philanthropic Ross Foundation, began in 1966.

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform

Local economic changes resulted from sharp economic downturns in 1974, 1979, and 1987, as well as the violent and deadly tornado of March 1, 1997. Ouachita Marine folded in 1991 after being bought out by Grumman, though Alumacraft continued to produce boats. In 1973, Group Living—a private, nonprofit counterpart to the Arkansas Children’s Colony—began serving adults with developmental disabilities and became a Main Street fixture through its Beehive resale shop and Honeycomb restaurant. Henderson State College became a university in 1975, though enrollment gains after the mid-1980s swelled its residential base little. The formation of the Dawson Educational Cooperative to aid regional public schools strengthened the importance of education as an economic force in the town. The Clark County Industrial Park opened south of town in 1979, but its presence did not forestall the loss of more than 1,000 jobs between 1980 and 1987, when Reynolds, Levi Strauss, and Fafnir Bearing Company closed and unemployment reached almost eleven percent. Slowly, the local economy replaced jobs, in part through the advent of Southern Development Bancorporation. Martha Dixon’s Dixon Manufacturing began producing apparel; Value-Line opened in 1985 to make furniture (though it closed in 2004); AALF’S Manufacturing occupied the Levi Strauss facility in 1988 to continue apparel manufacturing (but closed in 2001); and Petit Jean Poultry and Carrier/Scroll Technologies moved into the Industrial Park in 1991.

Arkadelphia continued to revitalize after the March 1, 1997, tornado, mainly because of the planning undertaken by the Arkadelphia 2025 Commission. Formed after the tornado in response to President Bill Clinton’s urging to ask not how to return Arkadelphia to its pre-tornado existence but how to achieve what the town wanted to be in 2025, the commission engaged a broad spectrum of the community and drew local leadership into that process. A commitment to promoting and maintaining a viable and vibrant downtown led to the formation of Streetscape to spearhead that effort and to a restored and remodeled courthouse and new downtown post office, police station, and town hall.

The Daily Siftings Herald ceased publication in September 2018. It was replaced later that year by the weekly Arkadelphia Dispatch.

Attractions

Arkadelphia has a long list of properties on the National Register of Historic Places. The Arkadelphia Boy Scout Hut is a log building located in Central Park that was constructed by local boys and members of the National Youth Administration (NYA) in 1938–39, and is today owned by the city and used by various Boy Scout and Girl Scout groups. The Clark County Library is located within the bounds of the Arkadelphia Commercial Historic District. The C. E. Thompson General Store and House served as both a store and a home into the mid-twentieth century before being renovated for use as a restaurant. The Rosedale Plantation Barn, built around 1860, is the largest known log barn in Clark County (and possibly the state). The Nannie Gresham Biscoe House, built in 1901, has interestingly passed through several generations of mothers and daughters, all of whom were educators.

Magnolia Manor was constructed outside the city limits but the town grew to encompass it. John B. McDaniel, who oversaw the construction of the home between 1854 and 1857, is buried in the historic Rose Hill Cemetery.

Peake High School, constructed in 1928, served Arkadelphia as the only public school for African Americans until 1960. From that point in time it continued to be of use as an elementary school, a middle school, a Headstart facility, and a storage facility. After undergoing extensive renovations, the historic building now houses the school district’s pre-kindergarten program.

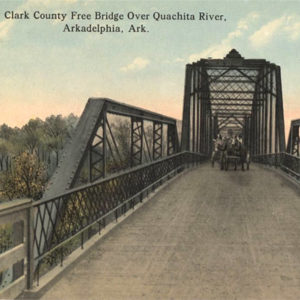

The following National Register properties represent the wide range of Arkadelphia’s history: the Hudson-Jones House, an antebellum home that was constructed around 1840; the Flanagin Law Office, built in 1858; the James E. M. Barkman House, built in 1860; the Habicht-Cohn-Crow House, constructed in 1870; the Captain Charles C. Henderson House, completed in 1906; the Domestic Science Building, constructed in 1917; the W. H. Young House, constructed in 1921; and the Arkadelphia Bridge, built in 1933 (and moved in 1960).

The Missouri Pacific Depot, built in 1917, continues to function as an active train depot for Amtrak travelers, as well as housing the Clark County Historical Museum. The Dexter B. Florence Memorial Field is an airport owned by the city used for both local general aviation and for Henderson State University flight operations.

Notable Figures

Arkadelphia residents of note include: Flave Carpenter, who selected two of the AP&L dam sites; historian Farrar Claudius Newberry; track and field star Skinny Whipple; businesswoman Jane Ross; prolific Christian author Ace Collins; composer/conductor William Francis McBeth, who taught at Ouachita Baptist University; Arkansas Supreme Court justice Otis Turner; renowned baseball player Delores Brumfield White; and journalist Rex Nelson.

Winston Peabody “Wimpy” Wilson was a major general in the U.S. Air Force. Born in Arkadelphia, Wilson enlisted in the Arkansas National Guard, became a pilot, and served during both World War II and the Korean War before serving as the chief of the National Guard Bureau. Nationally recognized cancer researcher Daisilee Berry spent her teenage years in Arkadelphia, while renowned artist V. L. Cox grew up in the community and graduated from Henderson.

For additional information:

Arrington, Michael E. Ouachita Baptist University: The First Hundred Years. Little Rock: August House, 1985.

Bledsoe, Bennie Gene. Henderson State University: Education since 1890. Houston: D. Armstrong Co., 1986.

Granade, S. Ray. An Enlarged Tent: First Baptist Church, Arkadelphia, Arkansas, 1851–2001. Arkadelphia, AR: First Baptist Church, 2000.

Hall, John Gladden. Henderson State College, the Methodist Years, 1890–1929. Arkadelphia, AR: Henderson State College Alumni Association, 1974.

Richter, Wendy, ed. Clark County Arkansas: Past and Present. Arkadelphia, AR: Clark County Historical Association, 1992.

Syler, Allen, et al., eds. Through the Eyes of Farrar Newberry: Clark County, Arkansas. Arkadelphia, AR: Clark County Historical Association, 2002.

S. Ray Granade

Ouachita Baptist University

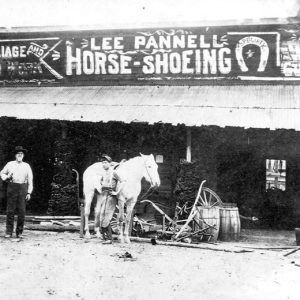

Arkadelphia Blacksmith Shop

Arkadelphia Blacksmith Shop  Arkadelphia Commercial Historic District

Arkadelphia Commercial Historic District  Arkadelphia Freedmen's Bureau

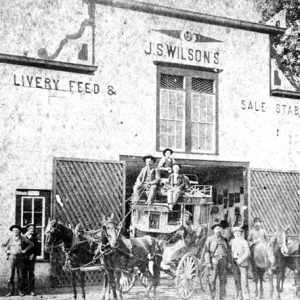

Arkadelphia Freedmen's Bureau  Arkadelphia Livery Stable

Arkadelphia Livery Stable  Arkadelphia Methodist College

Arkadelphia Methodist College  Arkadelphia Methodist College

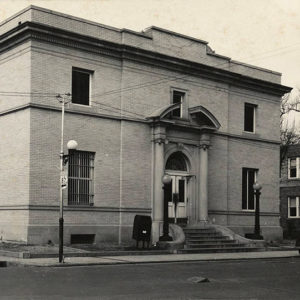

Arkadelphia Methodist College  Arkadelphia Post Office

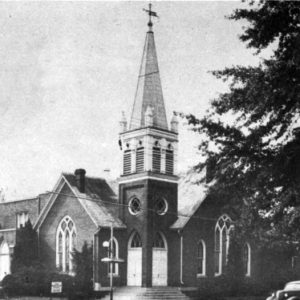

Arkadelphia Post Office  Arkadelphia Presbyterian Church

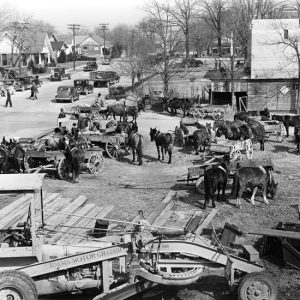

Arkadelphia Presbyterian Church  Arkadelphia Street Scene

Arkadelphia Street Scene  Arkadelphia Street Scene

Arkadelphia Street Scene  Arkadelphia Street Scene

Arkadelphia Street Scene  Arkadelphia Fire

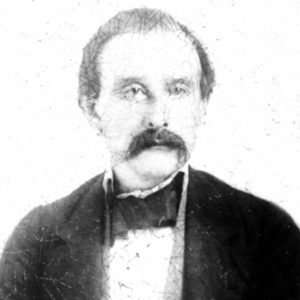

Arkadelphia Fire  Jacob Barkman

Jacob Barkman  James E. M. Barkman House

James E. M. Barkman House  Caddo Hotel

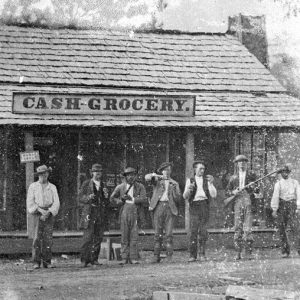

Caddo Hotel  Cash Grocery

Cash Grocery  Clark County Courthouse

Clark County Courthouse  Clark County Courthouse

Clark County Courthouse  Clark County Free Bridge

Clark County Free Bridge  Clark County Museum

Clark County Museum  Clark County Map

Clark County Map  Clark County Public Library

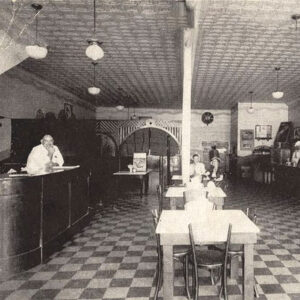

Clark County Public Library  Co-ed Cafe

Co-ed Cafe  De Lamar Motor Company

De Lamar Motor Company  Flanagin Law Office

Flanagin Law Office  Habicht-Cohn-Crow House

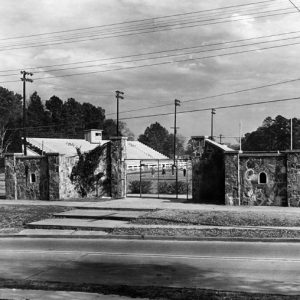

Habicht-Cohn-Crow House  Henderson State University Haygood Field

Henderson State University Haygood Field  Henderson State University

Henderson State University  Maddox Street

Maddox Street  Ouachita Baptist College Chapel

Ouachita Baptist College Chapel  Ouachita Baptist University

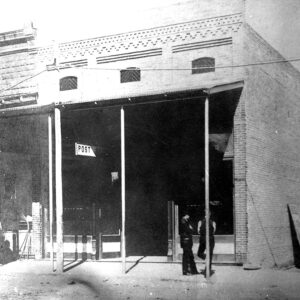

Ouachita Baptist University  Post Office, 1890s

Post Office, 1890s  Salt Kettle

Salt Kettle

Dr. Jerry E. Swayze saved Arkadelphia and Clark County from the smallpox outbreak of 1901.

Siplast, Inc., in Arkadelphia is a world-class roofing manufacturer that was initially French owned; it purchased the Tectum plant site in 1979 and 1983. Siplast expanded in 1995 to increase production. Siplast is now owned by Standard Industries, an American company that is part of one of the world’s largest roofing and waterproofing companies.