calsfoundation@cals.org

Wade Thomas (Lynching of)

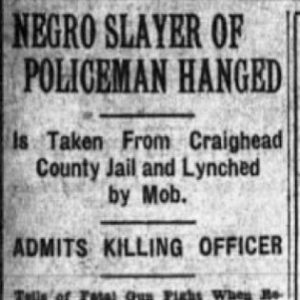

On December 26, 1920, a gambler and petty thief named Wade Thomas was lynched in Jonesboro (Craighead County) for the alleged shooting of Elmer “Snookums” Ragland, a white police officer.

Thomas, also known as “Boll Weevil,” was a Jonesboro native but had recently returned from “up North.” According to the Arkansas Gazette, he was known as a “‘bad’ and impudent negro,” who had formerly served time in the Arkansas penitentiary for highway robbery. According to Jonesboro historian Lee A. Dew, Thomas made his living by playing craps and engaging in petty thievery.

Dew recounts that Ragland had arrived in Jonesboro from Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) not long before he was killed. The Gazette reported that he was an “efficient and fearless officer.” Dew asserts that the Jonesboro police force had tended to ignore petty crime and vice in the town’s small, self-contained African-American neighborhood. In this period so soon after World War I, however, black Arkansans began to agitate for their rights with a new energy, and many white citizens felt that they could no longer exert the same control over them. According to Dew, Ragland had “soon gained quite a reputation as a ‘nigger-hater’ and was the only member of the all-white police force who prowled the black section looking for trouble.” He broke up dances that he claimed were disturbing the peace, and he raided dice games and arrested the participants.

On the night of December 25, 1920, Thomas, who was armed with a pistol, was playing a game of craps with a number of other African Americans. Ragland raided the game, and shots were fired. Ragland was killed, and Thomas was injured. Thomas then escaped, traveling twenty-three miles to Hoxie (Lawrence County). Officers there arrested a black man who was about to board a northbound train. They informed the Jonesboro chief of police, Gus Craig, and he took several officers with him to take custody of Thomas. When they arrived, they discovered that the officers in Hoxie had the wrong man, but they recognized Thomas on the platform, took him into custody, and returned to Jonesboro.

The citizens of Jonesboro learned of these events on December 26, which was a Sunday. According to Dew, they “reacted with horror, fear, and resentment. Groups of men huddled in grim conversations outside the doors of the churches….After dinner groups of men began to appear on the downtown streets, standing in small clusters and whispering among themselves furtively. Tension gripped the town.” This alarmed both Craig and Jonesboro mayor Gordon Frierson. They were determined to protect Thomas, but they were afraid that the crowd was getting out of hand. In an attempt to defuse the situation, they called a coroner’s jury, which indicted Thomas for murder. In addition, according to the Gazette, three of Thomas’s companions—Monroe Young, Banks Duncan, and George Clark—were charged as accessories, along with Draper Chatman, John Conway, and Oscar Johnson as material witnesses. All were jailed pending the next session of the circuit court.

By mid-afternoon on December 26, however, Frierson and Craig were becoming increasingly alarmed. They asked circuit court judges R. E. Lee Johnson and R. H. Dudley to join them at the jail. By 5:00 p.m., the crowd, which by then numbered around 500, had arrived at the jail. According to the Gazette, when the mob stormed the jail, judges Johnson and Dudley “urged the men to allow the law to take its course.” Johnson said he would try Thomas at a special session of the circuit court on January 12. The crowd, however, told the judges to leave unless they wanted to witness the lynching. They then took the keys from the jailor and approached the cellblock.

According to Dew, Frierson and Craig, armed with shotguns, had barricaded themselves inside. In the end, however, they did not resist the mob. Dew recounts that the mob’s leaders wore no masks and were widely known in Jonesboro. Frierson later told his nephew that he and Craig failed to defend Thomas because “when the mob opened the door, the first half-a-dozen men standing there were leading citizens—businessmen, leaders of their churches and the community.”

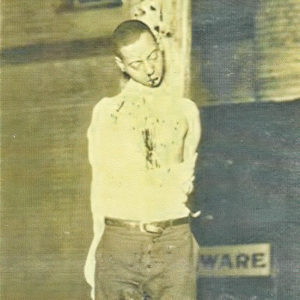

After being removed from his cell, Thomas—with a noose around his neck—was marched to a telephone pole at the intersection of Main and Monroe streets. According to the Gazette, the mob was orderly, and, “En route to the point where the lynching took place, the negro walked erect and apparently with no concern….He admitted killing Policeman Ragland, but claimed that he did not fire until after he had been wounded twice. He displayed a bullet wound in the right shoulder and another in the hand.”

Once they reached Monroe Street, a young boy climbed the pole with the end of the rope, and threw it over the crossbar to those waiting below. Dew reports that “a dozen pairs of hands grabbed the rope and twisted Boll Weevil into the air.” This failed to break Thomas’s neck, and he was ultimately shot in “a fusillade of bullets from the pistols, rifles and shotguns of the mob.” There was some talk of lynching Thomas’s companions, but officers persuaded members of the mob to let the law take its course. The crowd “slowly began filtering away,” leaving Thomas’s body to hang for several hours. It was later cut down by some of Jonesboro’s black citizens and buried in an unmarked grave.

According to Dew, on December 27, Jonesboro’s black citizens issued a statement saying that they understood “the sentiments and feeling of our people here…and we know their good feeling toward the good white people of the community and know that our people are proud of the good relations that exist between them.” Whites responded positively, Dew stated, “although most whites felt that justice had been done, and that Boll Weevil had ‘gotten what he deserved.’”

For additional information:

Dew, Lee A. “The Lynching of “Boll Weevil.” Midwest Quarterly 12 (January 1971): 145–153.

“Jailer Gives Keys to Howling Lynchers.” Chicago Defender, January 1, 1921, p. 1.

“Negro Fiend Lynched.” Jonesboro Evening Sun, December 27, 1920, p. 1.

“Negro Slayer of Policeman Hanged.” Arkansas Gazette, December 27, 1920, p. 1.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Wade Thomas Lynching

Wade Thomas Lynching  Thomas Lynching Article

Thomas Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.