calsfoundation@cals.org

Carl Edward Bailey (1894–1948)

Thirty-first Governor (1937–1941)

Carl Edward Bailey, a two-term governor of Arkansas in the 1930s, struggled to modernize state government and to cope with the Great Depression. He led a political faction consisting of state employees, which clashed with a coalition of federal workers over control of patronage. This conflict split the Democratic Party as well as the state into opposing political blocs.

Carl Bailey was born on October 8, 1894, in Bernie, Missouri, to William Edward Bailey and Margaret Elmyra McCorkle. His father worked as a logger and hardware salesman. Bailey grew up in Campbell, Missouri, where he graduated from high school. He attended Chillicothe Business College in Missouri but lacked the funds to graduate. He held a series of jobs and read law in his spare time.

Bailey married Margaret Bristol on October 10, 1915, and they had six children. Bailey was admitted to the practice of law in 1922. He and his family moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County), where he opened a private law practice in 1924.

In 1926, Bailey successfully campaigned for Boyd Cypert for prosecuting attorney of the Sixth Judicial District (covering Pulaski and Perry counties), and Cypert named him deputy prosecuting attorney. In 1930, Bailey became Cypert’s successor.

Bailey gained statewide attention in prosecuting A. B. Banks, the owner of an Arkansas banking empire that collapsed in 1930. He charged Banks with accepting deposits in a bank he knew to be insolvent. The lead defense counsel, U.S. Senator Joseph Taylor Robinson, argued that Banks had been made a scapegoat. In a dramatic trial, Banks was found guilty and sentenced to a year in prison, but he received a gubernatorial pardon. While the Banks case garnered Bailey popular acclaim, it also earned him the enmity of Robinson, the state’s most powerful political figure.

As the United States entered the Depression, Arkansas highway bonds were in default, and the state treasury was virtually empty. Although embarrassed, the Arkansas political establishment strengthened its position in the early 1930s. Under the New Deal, the federal government created scores of new jobs in Arkansas, which Robinson, as Senate majority leader, controlled. Robinson and Internal Revenue Collector Homer Martin Adkins formed a powerful federal-state coalition that dispensed patronage and favors. In opposition, Bailey and Brooks Hays led a reform faction within the Democratic Party. This rivalry dominated Arkansas politics for the next decade.

After four years as prosecuting attorney, Bailey ran for attorney general in 1934 and won in a close race. As attorney general, he garnered popular support by advocating welfare programs to assist the aged and needy. He also benefited from another sensational criminal case. In 1936, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, a New York gangster, fled to Hot Springs (Garland County) to escape arrest. Luciano was arrested and held for extradition hearings, but Hot Springs officials released him on a token bail. New York Special Prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey appealed to Bailey, who ordered the state police to take Luciano into custody. Declaring that “Arkansas cannot be made an asylum for criminals,” Bailey refused a $50,000 bribe to deny extradition, and Luciano went back to New York for trial.

In 1936, when the Robinson-Adkins faction failed to rally around a candidate for governor, Bailey won with a thirty-two percent plurality under contemporary election laws. His most important legislative achievement was the creation of a civil service system requiring many state employees to pass merit exams. Bailey also favored reforms in the new state Department of Public Welfare to qualify Arkansas for full federal funding.

Bailey had served as governor just over six months when Senator Robinson’s death in 1937 threw state politics into turmoil. Bailey jumped at the chance to go to the U.S. Senate, and the Democratic state committee, which he controlled, nominated him for the office. The anti-Bailey forces supported Adkins, who recruited Congressman John E. Miller to run as an independent. With the endorsement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and members of his cabinet, Bailey ran as a loyal New Dealer, but Miller, supported by Arkansas’s federal officeholders, won easily.

Privately, Bailey was bitter and feared that he might be a one-term governor. In a special legislative session, he regained some prestige by enacting a highway program. In the 1938 governor’s race, Bailey, admitting he had made mistakes, defeated R. A. Cook, a former Pulaski County judge.

In his second term, Bailey faced a tumultuous legislature, which repealed the new but widely unpopular civil service system. Bailey quietly favored repeal because he had come to realize that he could not command support without political patronage to dispense.

In 1940, Bailey broke tradition and ran for a third term. His opponent was Homer Adkins, the leader of the federal faction. At last, the two antagonists challenged each other openly. In an acrimonious campaign, Adkins won.

Bailey resumed his law practice in Little Rock and founded the Carl Bailey Company, an International Harvester franchise. He and his wife divorced, and he married Marjorie Compton in 1943. He remained politically active. When Adkins ran for the U.S. Senate in 1944, Bailey supported his opponent, J. William Fulbright, who won the race and began a long career in the Senate.

On October 23, 1948, Bailey died of a heart attack at age fifty-four. He is buried at Roselawn Memorial Park in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Wayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography, 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Holley, Donald. “Carl E. Bailey, the Merit System and Arkansas Politics, 1936–1939.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 45 (Winter 1986): 291–320.

Ledbetter, Calvin R. Jr. “Carl Bailey: A Pragmatic Reformer.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Summer 1998): 134–159.

Pierce, Michael. “How to Win a Seat in the U.S. Senate: Carl Bailey to Bill Fulbright, October 20, 1943.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 76 (Winter 2017): 334–361.

Donald Holley

University of Arkansas at Monticello

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Politics and Government

Politics and Government Bailey Family

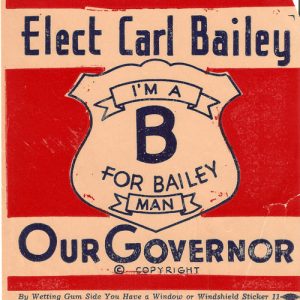

Bailey Family  Carl Bailey Sticker

Carl Bailey Sticker  Carl Bailey

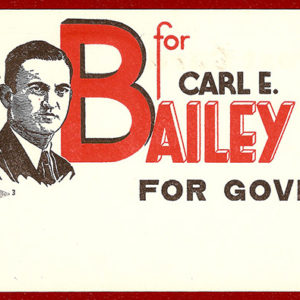

Carl Bailey  Carl Bailey Postcard

Carl Bailey Postcard  Carl Bailey

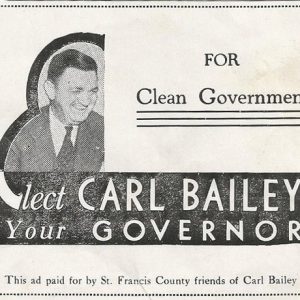

Carl Bailey  Carl Bailey Ad

Carl Bailey Ad  Bailey Reelection Campaign

Bailey Reelection Campaign  Oren Harris and Others at State Fair

Oren Harris and Others at State Fair  Razorback Stadium Dedication

Razorback Stadium Dedication

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.