calsfoundation@cals.org

Little Rock Convention of Colored Citizens (1865)

With only a month remaining in 1865, not long after the Civil War ended, African-American leaders and their white allies and guests met in Little Rock (Pulaski County). The Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Arkansas met from Thursday, November 30, through Saturday, December 2. Conventions of African Americans, led by free blacks, had been held frequently in cities in the North in the three decades before the outbreak of the Civil War. Continuing in that tradition, the Colored Convention in Little Rock was an organized effort by African Americans in Arkansas to make their commitment to the duties and rights of full citizenship known to white political and economic leaders, even in the state’s uncertain new postwar reality.

The organization and resolutions presented at the Northern antebellum conventions informed the meetings conducted by newly freed African Americans in the South, such as those in Little Rock in 1865. African Americans in the South mobilized quickly in the months after the conclusion of the Civil War to form social and political organizations in order to protect newly granted emancipation as well as advocate for greater civil rights and economic opportunity. Southern blacks and their newly formed organizations embraced northern blacks who assisted with organizational efforts and contributed legal knowledge and language for proceedings. Those groups almost universally asked for concrete political and civil opportunities, while they also called on other African Americans to embrace values of hard work, diligence, and thrift. Conventions, assemblies, and other official organizational efforts rarely asked for land redistributions, but instead sought fuller citizenship.

The Reverend J. T. White of Phillips County served as president of the Little Rock convention, the Reverend W. W. Andrews served as vice president, and J. W. Demby served as secretary. Upon the opening of the convention, Rev. White stated that its purpose was to declare to the Arkansas General Assembly and to the U.S. Congress the desire to be permanently granted “equality before the law, and the right of suffrage.” White’s justification, as recorded in the published proceedings of the convention, was very direct: “We have earned it and therefore, we deserve it; we have bought it with our blood.”

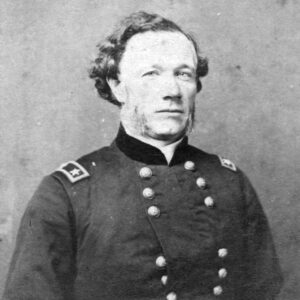

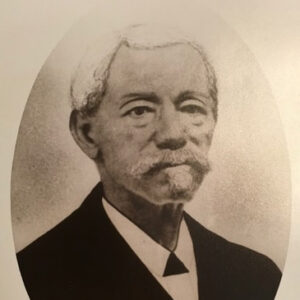

On its first day, the convention also formally invited Governor Isaac Murphy, General Joseph J. Reynolds, and General John W. Sprague to attend and address the meeting. The delegates who attended the convention as recorded in the proceedings were: Rev. White of Phillips County, David Young of Chicot County, John A. Jones of Pulaski County, W. W. Andrews of Pulaski County, A. L. Richmond of Pulaski County, E. W. Armstead of Pulaski County, B. Right of Pulaski County, Wilson Brown of Pulaski County, Nathan Warren of Pulaski County, Jesse Lawson of Dallas County, Yancey Bowlen of Dallas County, and George Sewell of Sebastian County. The second day, two more delegates from Phillips County arrived: William H. Grey and Richard E. Wall.

Conventions emerged even as African-American communities in both urban and rural areas expressed distrust of the federal government’s desire or intention to redistribute land and other capital seized from Southern whites, as well as punish former rebels. The primary concern for newly freed African Americans was education. Even in the years before the war, African-American leaders had stressed the need for education as a means of pursuing better economic opportunity. At the Colored Convention in Little Rock, leaders asked the state to help provide that essential education for African-American children, even as the members of the convention remained realistic about their place on the social ladder.

Southern Colored Conventions included frequent references to Frederick Douglass and the leaders of black liberation thought who had coordinated with abolitionists and organized for structural reform before the war. Colored Conventions often embraced the idea of labor as a negotiating tool, and while African-American leaders expressed a desire for all able-bodied blacks to provide their labor and to fill the desperate need for agricultural workers, they also demanded the reward of civic participation, alongside equitable pay, for providing labor. They hoped to formalize the use of their labor as a bargaining chip. Along with prayers and convocations, the Little Rock convention included scholarly remarks regarding the journey of and progress of African Americans.

These conventions also sometimes included prominent white political and business leaders as guests. In Little Rock, Unionist governor Isaac Murphy addressed the convention, which passed resolutions of appreciation for his recognition of the convention and for his support of the Union and emancipation.

The Little Rock convention’s resolutions and hoped-for outcomes—universal male suffrage, full political participation, greater economic opportunity, and social advancement determined by hard work instead of race—were similar to those of other such conventions. However, in the last months of 1865, black and white groups in Arkansas and across the South became anxious as both groups suspected that armed violence was imminent. They awaited, albeit with varying expectations, greater federal intervention. In Arkansas, Presidential Reconstruction—and the tenuousness of efforts to restrict the political participation of former Confederates—allowed successful, statewide organization of anti-Unionist conservatives. During the later Congressional Reconstruction and Republican control of Arkansas, several African-American leaders achieved election to state and federal offices. After the end of Reconstruction, however, the rise of Democratic Conservative rule, racial terrorism, and institutionalized segregation made it clear that the hopes of the members of the Colored Convention of 1865 would take far longer to be fully realized.

For additional information:

Colored Conventions Project. https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/ (accessed October 29, 2020).

“Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Arkansas. Proceedings of the Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Arkansas: Held in Little Rock, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, Nov. 30, Dec. 1 & 2.” Helena, AR: Clarion Office Printing, 1866. Land of (Unequal) Opportunity: Documenting the Civil Rights Struggle in Arkansas, a digital project of the University of Arkansas Libraries. http://digitalcollections.uark.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Civilrights/id/942 (accessed February 13, 2018).

Foreman, P. Gabrielle, Jim Casey, and Sarah Lynn Patterson, eds. The Colored Conventions Movement: Black Organizing in the Nineteenth Century. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021.

Moneyhon, Carl H. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Rosen, Hannah. Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Joshua Cobbs Youngblood

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Politics and Government

Politics and Government Joseph J. Reynolds

Joseph J. Reynolds  Nathan Warren

Nathan Warren

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.