calsfoundation@cals.org

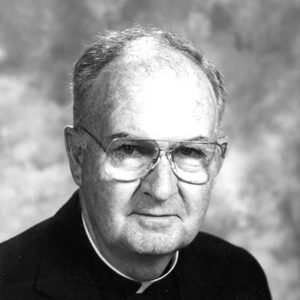

George Tribou (1924–2001)

Father George William Tribou was an influential figure in Catholic educational and community affairs in Arkansas, primarily through his position as principal and rector of Catholic High School for Boys in Little Rock (Pulaski County).

George Tribou was born in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 1924, to George and Mary Tribou. His father was an electrician, and his mother was a waitress; he had two sisters. After high school, he entered seminary in Philadelphia and completed the equivalent of a college curriculum. Area seminaries in the Northeast were rather crowded, so he relocated to St. John Catholic Seminary in Little Rock to complete his education for the priesthood. He was ordained as a Catholic priest on September 1, 1949.

His first assignment was as pastor of the mission in Sheridan (Grant County). He also served as assistant editor to The Guardian, the predecessor of the diocesan weekly newspaper Arkansas Catholic. Among collateral duties, he was chaplain for St. Vincent Infirmary and St. Joseph Orphanage. He was also chaplain for the Carmelite Monastery of St. Theresa, a position he continued throughout his career. He alternated with another priest to conduct mass for the nuns every morning.

In 1950, the bishop assigned him to teach at the Catholic High School for Boys, then located at Roosevelt and State streets. He taught various subjects, primarily English. During summer vacations, he studied and received a master’s degree from Villanova University and also studied at Temple University in Philadelphia and Catholic University in Washington DC. He continued to teach English classes throughout his career at Catholic High.

In 1961, Catholic High was moved to a new, large campus on Lee Street. Tribou was named principal and rector of the school in 1966. He taught in the school for fifty years and was principal for thirty-four years. Early in his teaching career, he established a reputation for being strict and demanding, but also kind and helpful to his students with academic or personal problems.

Under his leadership, Catholic High was noted for academic success and strict discipline, including a dress code requiring acceptable haircuts, khaki pants, white shirts, and neckties. Several of the alumni returned in later years to become teachers at the school and carried on the traditions that Tribou established.

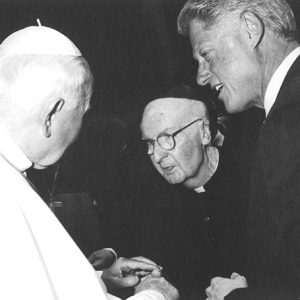

Tribou was a friend of Bill and Hillary Clinton, though they differed greatly on the issues of abortion and capital punishment. In 1999, President Bill Clinton made arrangements to introduce Father Tribou to Pope John Paul II, who was visiting St. Louis, Missouri. Clinton told the pope, “He’s the premier educator in the state. This is my very good friend, but he doesn’t vote for me.” A photo of the three men put on display at Catholic High was labeled: “Father Tribou and Two Other Guys.”

Tribou had a habit of cigar smoking (though he was the only one allowed to smoke at the school), and his students could predict his classroom visit because the cigar odor preceded him. His dog accompanied him in his frequent trips around the school halls. Known for both his wit and his wisdom, Tribou was a popular master of ceremonies and speaker at meetings.

Tribou was given the honorific title of monsignor in 1993 in recognition of his many contributions to his church. While flattered by the honor, he said he preferred to be known as “Father,” lest he seem too remote from his boys, and most people continued to call by the familiar “Father.”

Tribou died on February 2, 2001, after a battle with cancer. His funeral was held at Catholic High School in the gym with a service in the morning for students and their families and one after school for the public. The gym was filled at each service. In the eulogy, Monsignor Gaston Hebert said, “It is my contention that no other priest in the history of our diocese has so influenced as many lives in such a permanent fashion as this remarkable, great priest. He was the right man in the right place at the right time.” After his death, the section of Lee Street on which Catholic High is situated was renamed Father Tribou Street.

For additional information:

“Father George W. Tribou, 1924–2001.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 6, 2001, p. 6B.

Moran, Michael J. Proudly We Speak Your Name: Forty-four Years at Little Rock Catholic High School. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2009.

Oman, Noel. “Father’s Flock Says Goodbye.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 7, 2001, pp. 1B, 12B.

———. “Tribou, 76, Dies of Ills after Surgery.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 3, 2001, pp. 1A, 10A, 11A.

Rains, Judy. “George William Tribou.” Arkansas Democrat, August 13, 1989, High Profile Section, pp. 1, 9.

W. W. Satterfield

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Education, Elementary and Secondary

Education, Elementary and Secondary Religion

Religion George Tribou Birthday

George Tribou Birthday  George Tribou

George Tribou  Young George Tribou

Young George Tribou  George Tribou Funeral

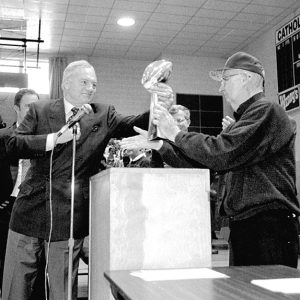

George Tribou Funeral  Tribou Meets the Pope

Tribou Meets the Pope

Tribou Tales: Part 6: In 1984, a lawyer in the Public Defenders Office called Father Tribou and asked if he would counsel with a teenage client, and he agreed to help. Stephen Douglas Hill, age eighteen, was accused of killing an Arkansas State policeman. He apparently had no family or friends. Father Tribou met and visited with the young man in jail and developed a relationship. The teenager was tried for murder, convicted, and sentenced to death. Hill asked, Father youre not going to desert me now are you? Father assured him that he would stick with him. Tribou visited with Governor Bill Clinton at the Governors Mansion to discuss the situation. He said that he could tell that the governor was visibly shaken by what he said was his legal obligation to proceed with ordering the execution. Hill wrote to Tribou: This is going to be one of the best Christmass Ive had because this year I have something I have never had before, and that is a best friend, a true friend, a true best friendyou. Father Tribou was present at the execution in 1992.

Tribou Tales: Part 5: A parent once asked Tribou why he made the boys suffer through early fall and late spring weather without air-conditioning. His reply was, Its hot for the first two weeks and the last two weeks, but hey, its only forty days and they can handle that. Christ was in the desert for forty days and forty nights. They can be in the classroom. *** A family asked Father Tribou if he would consider enrolling their son, who had been expelled from three separate high schools in town. The lad was invited to a Saturday morning interview. After their conversation, Father showed the boy around the school and then asked him, Well, what you think of our school? The defiant young man said, I think its a piece of (****). Father Tribou took a draw on his cigar and said, I think you will fit right in. Report Monday morningproperly dressed.The student did enroll, graduated with the class of 1978, and told his classmates that Father Tribou and the Catholic High discipline turned his life around and saved him. He went on to have success in his occupational and family life. *** From his first days as an ordained priest, Father Tribou, as a collateral duty, served as chaplain for the Carmelite Monastery of St. Theresa in Little Rock. Throughout his career, he alternated with Father Frederick in conducting mass for the nuns every morning. Sister Bernadette said, He would roast us and canonize us at the same time.

Tribou Tales: Part 4: Father Tribou spent several teenage years working in a movie theater. He gained not only a strong work ethic, but a love of drama. In later years, he made an annual trip to New York to see the latest Broadway plays. A Catholic High student, Alan, was absent from school the day before Thanksgiving holiday started, presumably to attend some church function. Actually, he had taken advantage of the opportunity to go to New York City, and he assumed Father Tribou would not excuse him for such purpose. He was standing on a street corner in Manhattan waiting for the light to change when there was a tug on his sleeve. He turned to see Father Tribou, who said, Alan, youd better behave yourself while you are here. Im keeping an eye on you. Tribou then quickly disappeared into the crowd. The next Monday, Alan sought out Father Tribou and said that he was really surprised to see him in New York. Tribou denied having been in New York and had two faculty members set up to verify his presence in Little Rock. Apparently, he never confessed to Alan, who was left wonderingand probably never played hooky again. While students frequently tried to trick Father Tribou or faculty, it was hard to keep ahead of him. (Father Tribou said the highlight of his life was having a fifteen-minute conversation with Katharine Hepburn in her dressing room on Broadway, and he said he had several notes from her.)

Tribou Tales: Part 3: In his book, Proudly We Speak Your Name, Mike Moran told a story of his undergraduate days at the old Catholic High School in 1960. Father Tribou asked him to stay after school and help him, and the young senior was flattered. The Little Rock police had called and reported that they had a vagrant fifteen-year-old who had run away from home. The boy said he was Catholic, so they asked Father Tribou if he would help. Tribou took the frightened, lonely youth in tow. He introduced Mike to the shaggy-haired lad and told him to take the boy to the barbe shop two blocks away and get him a haircut; the barber was expecting them. He then took the two boys to a nice dinner at the Lido Inn, a fine restaurant. After dinner he took the boy to the bus station, bought him a ticket home to Pennsylvania, and gave him $5.00 for the trip. The otherwise defiant young man was very grateful. This was not an unusual thing for Father Tribou to do, but it made quite an impression on young Mike. In later years when Mike, then a teacher at Catholic, mentioned it, Tribou claimed no memory of the incident. It was just part of his life to do such deeds and not make a big deal of it. Mike said that the story was an example of Wordsworths description of those little, nameless, unremembered acts of kindness and of love used to describe that best portion of a good mans life.

Tribou Tales: Part 2: A concerned patron called one day seeking advice. His ninth-grade son, Steve, who suffered from dyslexia, was having a difficult time keeping up academically. As sometimes happens, lacking academic inclusion, he turned to other contacts to find acceptance and companionship. Based on what he told his parents, it was apparent that he was under some bad influence, particularly from a new friend, Joe, a tenth-grader. In a phone call Father Tribou told the distraught father to not worry; he would take care of it. On the PA system he ordered Steve to report to the officeprobably a terrifying thing for a freshman. When Steve reported, Father Tribou looked up from his desk and said, Steve, I dont want you hanging around with Joe anymore. Steve said, Yes, sir. That was the last that was heard of Joe, and Steve was back on the right track.

Tribou Tales: Part 1: On the first school day after a senior prom, Father Tribou announced that a student was seen going to the parking lot during the dance and drinking alcohol he had hidden in the trunk of his car. He said that he had the license number and that student should report to the office immediately. About a dozen boys showed up. A similar situation occurred when he ordered the student who was seen smoking on campus the previous day to report to the office. Several boys showed up. The punishment for smoking on campus was to smoke one of Tribous cigars with a trash can inverted over the head. When two boys were disciplined for fighting, they were required to hold hands all the next day when in class or when walking in the halls. One boy who was guilty of continually and unnecessarily slamming a door in the restroom was required to detach the door and carry it around school all day. If a student was found to have a messy locker, he was required the next day to carry all of his books with him in a box. A boy caught sleeping in one of his classes was made to wear pajamas to school the next day. Anyone seen dancing too close at a prom was required to dance with a broom, or spend some time hugging a column. Father Tribou said of the Catholic High curriculum, We dont teach AP (advanced placement), we teach M&P (meat and potatoes.)