calsfoundation@cals.org

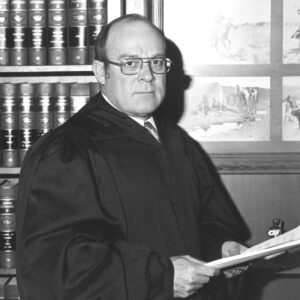

Darrell David Hickman (1935–)

Darrell David Hickman spent almost twenty-two years as a trial-court judge and justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court. Hickman, who grew up in Searcy (White County), was first elected chancery judge in a district that stretched to Little Rock (Pulaski County) and was elected twice to the Arkansas Supreme Court before retiring in 1990 to follow the seasons and travel from the Canadian Rockies to Mexico and back. He soon returned to Searcy and the town of Pangburn (White County), where he served two more stints as a chancery or circuit judge. Hickman had a propensity for issuing convulsive orders, such as when he declared the Constitutional Convention of 1975 unconstitutional, and for writing colorful opinions, such as when he declared the sweeping property-tax amendment of 1978 “the Godzilla of constitutional amendments.”

Darrell Hickman was born on February 6, 1935, in Searcy, one of two sons of Paul Hickman and Mildred Jackson Hickman. His father was laid off from the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad early in the Great Depression and struggled through the Depression with odd jobs until becoming a truck driver for Allied Transport Company. His mother opened a beauty parlor.

For two and a half years, Hickman attended Harding College (now Harding University) in Searcy and then transferred to the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). He spent three summers scaling logs at a lumber camp for the U.S. Forest Service around Fresno, California, before graduating from UA in 1958 with a law degree. He received a naval commission and spent six years in the service, two as the legal officer on the aircraft carrier USS Constellation. Hickman had two children during a first marriage before he entered the navy. The marriage ended in divorce after twelve years. In 1971, he married Kerry Hardcastle of Searcy, and he adopted her daughter.

Returning to Searcy in 1964, he opened a law practice and soon became a deputy prosecuting attorney. In 1966, he ran unsuccessfully for state representative in the Democratic Party primary in a district that covered White and Lonoke counties. He worked for losing candidates in the 1968 and 1970 elections for governor and, in 1972, decided to run for office himself. Although he lived on the northern edge of a district that included White, Lonoke, Prairie, and Pulaski counties (the last the most populous), he filed against Judge Kay L. Matthews of Little Rock (Pulaski County). Sitting judges were rarely opposed and almost never beaten, but Hickman carried Pulaski, White, and Lonoke counties and won handily, establishing a reputation as a nervy and canny politician. He easily won all his races thereafter.

Although chancery courts, which dealt with family and other equity matters, rarely made news, Judge Hickman’s court was different, mainly owing to his insistence that the terms of the state’s 1874 Constitution, even if they were outdated and needlessly restrictive, had to be strictly followed until the voters changed them. He declared the expense accounts of county officials unconstitutional, stopped Pulaski County from skirting the $5,000 constitutional limit on compensation for elected officials, and declared revenue bonds that were to build an office mall on the Arkansas State Capitol grounds unconstitutional. The Arkansas Supreme Court upheld his decision on county officials’ compensation, and a constitutional amendment two years later modernized county administration and compensation. Although the Supreme Court consistently upheld revenue bonds as a legal device for financing capital improvements, the state did not appeal his bond ruling, and ten years later the Supreme Court embraced his view that such bonds were unconstitutional.

In 1975, the Arkansas General Assembly enacted a law calling for a convention to rewrite most of the state constitution, the major plank in the program of the new governor, David Pryor. Republicans filed suit in Pulaski Chancery Court questioning the legality of the convention. Hickman ruled that the legislation was invalid because a few of the delegates were not elected but appointed by the legislature and because the act put a few highly controversial parts of the constitution off limits so that the delegates could not change them. Hickman allowed a hasty appeal, and the Supreme Court upheld the ruling 4–3 on the day the convention assembled at the Arkansas State Capitol.

As a chancellor, Hickman drafted legislation that redrew the boundaries of all the existing judicial circuits, made circuit and chancery districts co-extensive, and allowed a judicial circuit to consist of one judge serving both as circuit and chancellor. The act streamlined the trial courts and created a number of new judgeships.

His reputation for decisions that upset the status quo helped him get elected to the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1976, when Justice Lyle Brown retired. He defeated a circuit judge from El Dorado (Union County) and a former state representative from Little Rock for the seat to serve the last two years of Brown’s term and then was reelected. He was the first person from White County to be elected to a statewide office since Reconstruction.

On the state’s highest court, Hickman continued to vote against revenue bonds, but the court continued to uphold them. The Constitution of 1874 and several subsequent amendments required a popular vote before local governments or the state could incur debt, but the state had come up with the device of “revenue bonds” in the early 1930s to circumvent the provision. If revenues produced by a project rather than taxes were pledged to pay off bonds, the Supreme Court in 1934 agreed to consider the bonds not an obligation of the government and exempt from a popular vote. Revenue bonds began to be widely used for industrial development and state and local capital improvements.

For the next fifty-two years the Supreme Court upheld the bonds as exempt from the election requirements in the constitution. But when a case testing the validity of bonds issued by the city of Hot Springs (Garland County) to pay off earlier obligations for the bankrupt Magic Springs amusement park (City of Hot Springs v. Creviston) reached the Supreme Court in 1986, the court reversed itself and declared such bonds invalid because they were not authorized by a popular election. Justice George Rose Smith, who wrote the majority opinion, later said that the court was prepared to approve the bonds as usual, but Hickman had persuaded him and others in conference that, however worthy a project, the court should not be countenancing an obvious subterfuge to avoid a clear mandate of the state constitution. The financial houses and bond law firms quickly wrote a constitutional amendment (Amendment 65) to legalize revenue bonds, circulated petitions to get it on the ballot, and got it ratified in the general election that fall.

When a case (Clark v. Union Pacific Railroad) interpreting Amendment 59, which overhauled property-tax laws, reached the court, Hickman dissented from the majority’s interpretation, which said the amendment exempted the railroad from paying some personal property taxes. Hickman’s widely cited dissent began: “Amendment 59 is the Godzilla of constitutional amendments. Nobody knows what it means. It was the child of fear and greed spawned after our decision in 1979, which held that the Arkansas Constitution required that all property be assessed at market value.” His opinion suggested that someone file a lawsuit to strike down the whole amendment.

In 1982, Hickman persuaded the other justices to remove from the ballot a proposed constitutional amendment supported by Bill Clinton, who was seeking another term as governor, on the grounds that it was hopelessly confusing. The amendment, which was 10,000 words long, would have altered utility regulation. Hickman said that he timed himself reading merely the ballot title, and it look him five minutes; voters could not be in the ballot booth for longer than three minutes. The decision became the standard by which the court subsequently struck initiated amendments and acts from the ballot for being confusing or deceptive.

When the Arkansas Supreme Court was considering issuing rules for disciplining wayward judges or removing them when they became disabled, Hickman said the court had no such power and suggested that they amend the state constitution to create a special commission to discipline judges. He directed the drafting of the amendment (Amendment 66), the Arkansas General Assembly put it on the ballot in 1988, and the voters approved it.

Hickman retired toward the end of his term in 1990, intending to travel through the western United States and Canada, where he frequently went on extended motorcycle trips. He had been the Arkansas Supreme Court’s senior judge for four years, and four of his opinions had been the basis of major articles in the legal encyclopedia American Law Reports. But Hickman soon returned to Pangburn. Acting Governor Jim Guy Tucker appointed him to a vacancy on the circuit court in White County in 1992, and Governor Mike Huckabee appointed him to fill a vacancy on the chancery court in 2000 for two years.

For additional information:

“Hickman Wins With 60 Pct.” Arkansas Gazette, June 9, 1976, pp. 1A, 4A.

“Interview with Justice Darrell Hickman.” Arkansas Supreme Court Project. Arkansas Supreme Court Historical Society. https://www.arcourts.gov/sites/default/files/oralhistories/HICKMAN%20Interview.pdf (accessed October 14, 2020).

Oswald, Mark. “Associate Justice Set ‘to move on.’” Arkansas Gazette, February 21, 1990, pp. 1B, 6B.

Woodruff, Dianne. “Chancellor to Seek Seat on State Supreme Court.” Arkansas Gazette, January 10, 1976, p. 3A.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Law

Law Darrell D. Hickman

Darrell D. Hickman

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.