calsfoundation@cals.org

Gould (Lincoln County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 33°59’06″N 091°33’39″W |

| Elevation: | 164 feet |

| Area: | 1.55 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 663 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | August 24, 1907 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

57 |

318 |

827 |

908 |

1,076 |

1,210 |

1,683 |

1,671 |

1,470 |

1,305 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

837 |

663 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gould is a city in eastern Lincoln County, situated on U.S. Highway 65 and on the Union Pacific Railroad. Formed as a railroad city in the early twentieth century, Gould received national notoriety in the twenty-first century because of the fervor of its local political confrontations.

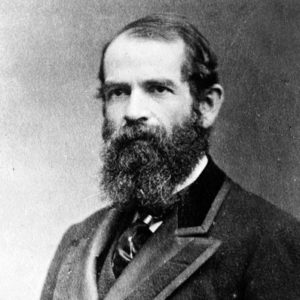

When Lincoln County was formed in 1871, the swampy land between the Arkansas River and Bayou Bartholomew was largely uninhabited. Between 1870 and 1873, construction of the Little Rock, Pine Bluff and New Orleans Railroad (which eventually became part of the Union Pacific) brought traffic through the area. The part of the line where Gould would soon be established was known briefly as Palmer Switch. George H. Joslyn Sr., the first county judge of Lincoln County, had a post office established at that location in 1904. For three years, the post office was known as Joslyn in his honor, but when a town was platted and incorporated at the site in 1907, organizers of the community named it Gould to honor railroad financier Jay Gould. Judge Joslyn’s son, Max Joslyn, was among the organizers of the town and was elected its second mayor in 1911.

At this time, Gould was described as “a village of one store and three saloons and about twenty shotgun type houses.” Two area schools had been organized: one that met in the Bailey Chapel Church and another two-room structure built west of Gould using a grant from Sears Roebuck & Co. An African-American school was organized in 1918 in a cabin attached to a sawmill, and a second school for black children was created through a grant from the Rosenwald Foundation in 1924.

The Bank of Gould was chartered on September 10, 1919; although it survived the early years of the Depression, it was closed and its assets liquidated on January 16, 1934. A fire department was organized in 1924. Several newspapers were published in Gould over the years, including the weekly papers Gould Advance, Gould Gazette, Gould Tribune, and Gould Journal; most were short lived.

A public library was organized beginning in the 1940s. It was located in the town hall, which was destroyed by fire on October 31, 1979. Many city records were salvaged from the ruins, although the library books and the water department records were destroyed. The regional library of Monticello (Drew County) lent a collection of books to Gould, which were held in a mobile unit near the railroad tracks until a new city hall was completed. In 1949, Gould reincorporated as a second-class city, establishing three wards to select aldermen to serve in the city government. The fire department acquired a new truck in 1957 and was reorganized at that time.

A U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1954 declared segregated schools unconstitutional, but the educational system in Gould remained largely unchanged for a decade. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) established a regional field office in Gould in 1964 and supported several African-American candidates for the Gould school board. (The black candidates lost the election that year in spite of the fact that Gould’s population was eighty-two percent black.) With assistance from SNCC, a complaint was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas addressing school facilities, freedom of choice in attending schools, instructional materials, teacher staffing, and money spent on each school. As a result of the suit, the Gould Special School District was fully integrated in September 1967, although some white families formed a private academy to keep their children out of the integrated schools. In May 1968, Raney v. Board of Education was one of three cases heard by the U.S. Supreme Court that brought an end to “freedom of choice,” a hold-out policy against integration. SNCC members also worked in Gould to integrate restaurants and public facilities and to challenge discriminatory enforcement of local laws.

In 2010, the population of Gould was 837, of whom 657 were black. Local businesses included one restaurant, one bank, a health clinic and dental center, and a cotton gin. There were also four churches and a U.S. National Guard armory.

The following year saw political turmoil in Gould as the mayor, Ernest Nash Jr., and the city council challenged each other over the financial plight of the city. In May 2011, Gould received a federal grant of $822,000 to improve the city’s sewer system, but around the same time, it was announced that the city owed the federal government $289,000 in back payroll taxes. A private group called the Gould Citizens’ Advisory Council met with the mayor to try to solve the city’s problems, but the city council responded by prohibiting public discussion of those problems and passing several ordinances restricting the power of the mayor—including stripping him of the authority to hire or fire city workers or to spend city funds. Although the city council reversed some of its decisions in the face of national attention (which suggested that their ordinances violated the right of free speech guaranteed in the Bill of Rights), Nash was attacked and injured at a local gas station that summer.

The city treasurer resigned in December, shortly after the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) chose not to seek back payments from the city. However, a confrontation in city hall that winter involving Mayor Nash and other city employees led to further charges, especially when it was found that, following flooding in 2011, the mayor had deposited relief funds from the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in a bank account that did not belong to the city. These charges were later dropped, but the mayor resigned in February 2014.

Gould is the birthplace of political activist Ozell Sutton and was the childhood home of quiltmaker Rosie Lee Tomkins. James and Ethel Kearney, who were recognized for their contributions to childhood education and Christian service by the State of Arkansas, resided just outside of Gould for much of their lives. Their daughter, Janis Kearney, worked in publishing most of her life and was the presidential diarist to Bill Clinton.

For additional information:

Frye, Cathy. “Gould to Repeal Laws on Groups.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 21, 2011, pp. 1B, 5B.

Finley, Randy. “Crossing the White Line: SNCC in Three Delta Towns, 1963–1967.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Summer 2006): 117–137.

Laver, Claudia. “Several Vetoes Undone in Gould. Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 14, 2011, pp. 1B, 7B.

Lincoln County Historical Committee. History of Lincoln County, Arkansas, 1871–1983. Dallas, TX: Taylor Publishing Company, 1983.

Worthen, John. “2 Arrested in Assault on Mayor of Gould.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 11, 2011, pp. 1B, 5B.

———. “Gould Given $822,000 to Solve Sewer Sorrows.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 30, 2011, pp. 1B, 6B.

———. “Gould Stuck as Judge Ends Mayor’s Trial.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 26, 2012, pp. 1, 7A.

———. “Gould Vehicles Face IRS Threat.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 8, 2011, pp. 1B, 10B.

———. “In Gould, Court Faces an Inquiry.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 25, 2012, pp. 1, 5A.

Steven Teske

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

Gould Aerial View

Gould Aerial View  Gould Hotel

Gould Hotel  Jay Gould

Jay Gould  Lincoln County Map

Lincoln County Map  Ozell Sutton

Ozell Sutton

Gould is a speed trap town–much of their revenue comes from it. Don’t drive there unless you have to.

Thomas James Kearney and Ethel Kearney were sharecroppers and parents of nineteen children, eighteen of whom were college graduates. Their daughter Janis Faye Kearney is the author of award-winning books, including “Cotton Field of Dreams,” about growing up in Gould and Lincoln County; she also purchased civil rights leader Daisy Bates’s newspaper in 1988 and served as personal diarist to President William J. Clinton from 1995 to 2001. Three Kearney sons–Jesse, John, and Jerome–have served as judges in the state of Arkansas.

My great-grandpa was president of the bank of Gould, but I don’t know the years. His name was John David Crockett.