calsfoundation@cals.org

Bearden Lynching of 1893

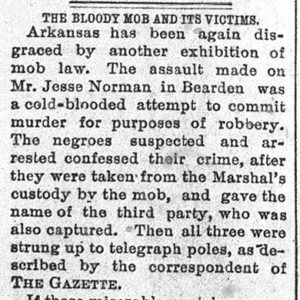

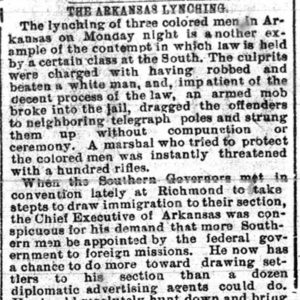

On May 9, 1893, three African Americans were lynched in Bearden (Ouachita County) for what was called a “murderous assault” on Jesse Norman, a prosperous young businessman.

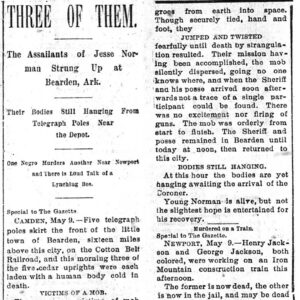

At midnight on Saturday, May 6, Jesse Norman was hit over the head with an axe and robbed. The victim was probably the Jessie J. Norman listed in the 1880 census, thirteen years before the event. In 1880, he was nine years old and was living with his parents Eleazer (variously spelled Elezer and Elesa) Norman and Panthaia (variously spelled Panttairer and Panthier) Norman in Union Township of Ouachita County; his parents were still living in the county in 1900. According to the Arkansas Gazette, Norman’s skull was crushed with an axe, and he was robbed and left for dead. He climbed out of the ditch into which he had been thrown and crawled home, where he was found unconscious by his sister the next morning. While he was still alive, “not the slightest hope [was] entertained for his recovery.”

Suspicion immediately fell on two black men “who were seen lurking around him that night.” They were jailed, and as Norman continued to lie in a coma, local citizens became irate. Armed men began to gather from surrounding communities, and between 300 and 500 men (though some accounts estimate the crowd at only fifty) demanded that the town marshal give them the keys “to the little pine prison.” He did so, and as they were removing the two prisoners from the jail, the prisoners supposedly implicated a third man, who was then captured at his home. The three accused were twenty-five-year-old Abe Craine, forty-five-year-old Doc Benson, and twenty-year-old Jim Stewart. According to both the Deseret Evening News and the Indianapolis Journal, the members of the mob were certain that they had the alleged criminals since the men had Norman’s pocketbook and other personal items in their possession.

Arkansas census records reveal nothing about Abe Craine. In 1876, Doc (or Dock) Benson married Julia Brazell in Ouachita County. By 1880, he was farming in Union Township, and he and Julia had three small children. Stewart may be the eight-year-old James Stewart listed in the 1880 census as living in South Fork Township in neighboring Clark County with his parents, Henry and Cynda. His father was a farmer, and his older brothers George and Dick were working as farm laborers.

At the same time the mob was seizing the alleged attackers, the sheriff was leading a posse from Camden (Ouachita County) to protect the prisoners. Hearing this, members of the mob immediately procured rope and hanged the “struggling negroes” from telegraph poles near the railroad line. The Gazette was quite graphic in describing this event. Apparently, the victims did not die quickly: “Though securely tied, hand and foot, they jumped and twisted fearfully until death by strangulation resulted.” By all accounts, the mob dispersed quietly and had disappeared by the time the sheriff arrived. In the morning, three of the telegraph poles along the Cotton Belt Railroad “were each laden with a human body cold in death.”

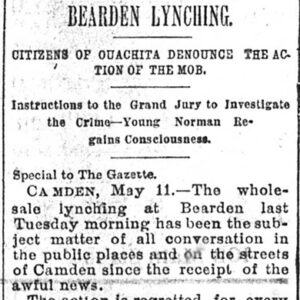

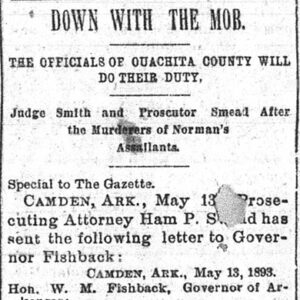

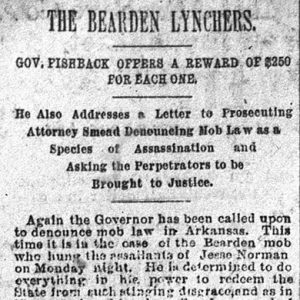

Governor William Fishback was reportedly outraged by these events and offered a $250 reward for each member of the mob who was arrested and convicted. He was determined to “redeem the State from such stinging disgrace,” and instructed H. P. Smead, the prosecuting attorney for the Thirteenth Judicial District, to pursue the culprits and convict them, as mob murder “can only be broken up by hanging a few of the participants and teaching them that we live in a land of law.” The Gazette also expressed outrage. Lamenting that the incident had “added another contribution to the black record of contempt for the law,” it urged “an uprising of the law-abiding people in favor of law and order.” By May 11, Judge Charles W. Smith of the circuit court had instructed the grand jury to investigate the crime and indict the perpetrators. By that time, Jesse Norman was speaking, and there was hope that he would recover. On May 14, the Gazette reported that all attempts to locate the members of the mob had been unsuccessful, although authorities were requesting the public’s assistance in identifying and capturing them.

For additional information:

“Begged for Mercy in Vain.” Deseret Evening News (Great Salt Lake City, Utah), May 9, 1893, p. 1.

“The Bearden Lynchers.” Arkansas Gazette, May 11, 1893, p. 3.

“Bearden Lynching.” Arkansas Gazette, May 12, 1893, p. 2

“The Bloody Mob and Its Victims.” Arkansas Gazette, May 11, 1893, p. 4.

“Down with the Mob.” Arkansas Gazette, May 14, 1893, p. 3.

“Three Negroes Lynched.” Indianapolis Journal, May 10, 1893, p. 2.

“Three of Them.” Arkansas Gazette, May 10, 1893, pp. 1–2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Anti-Lynching Editorial

Anti-Lynching Editorial  Anti-Lynching Editorial

Anti-Lynching Editorial  Bearden Lynching Article

Bearden Lynching Article  Bearden Lynching Article

Bearden Lynching Article  Bearden Lynchings Letter

Bearden Lynchings Letter  Fishback Lynchings Letter

Fishback Lynchings Letter

A few observations/questions:

1) The Norman family and the Benson family on the 1880 census are listed on the same page and only four dwellings between them at dwelling 54 and 59, respectively.

2) I wonder if this close proximity indicates other factors surrounding this event that have not been revealed or explored.

3) We are not told what happened to Julia Benson and her children after the event.

Notes:

– Brazil is variously spelled Braziel, Brazell, Brazzle, etc.

– Julia Brazil would be my great-grandaunt.