calsfoundation@cals.org

England (Lonoke County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34°32’39″N 091°58’03″W |

| Elevation: | 236 feet |

| Area: | 1.89 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 2,477 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | March 1, 1897 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

467 |

1,156 |

1,404 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

3,194 |

4,423 |

2,130 |

2,027 |

2,136 |

2,861 |

3,075 |

3,081 |

3,351 |

2,972 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2,825 |

2,477 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

England is a small farming community located in the southeastern part of Lonoke County. While England has a rich history as a center of agriculture, in the late twentieth century, it became a bedroom community for Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), though many local farmers still reside in the area. England lies in the alluvial flood plains of the Arkansas River. It was originally covered by hardwoods such as oak and red gum, but most of this natural vegetation has been removed for commercial farm crops. The soil surrounding England has been classified as some of the most productive in the country, supporting cotton, rice, soybeans, and corn.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

In the 1870s and 1880s, nineteen families, including that of Bob Hudgens, settled three and a half miles north of the modern-day town location. In 1880, a post office was established and named Groveland; the name was changed to England in 1888. Also in 1888, a small, one-room building was constructed to serve as a school, church, and meeting place for the growing community.

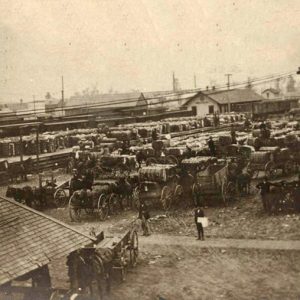

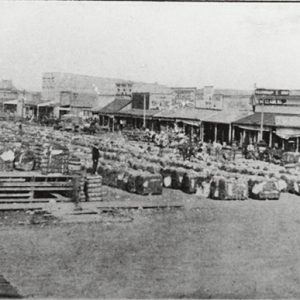

The late 1880s was a time of growth for England. The railroad made England a center of cotton production and trade, necessitating the establishment of a town. John Calhoun England, a landowner and lawyer for the Cotton Belt Railroad, purchased the original tracts of land that make up the town today and had them surveyed into lots. After the completion of the railroad in 1888, a township committee was formed to lay out the town and chose to name it after England. Initially, the postmaster general refused to allow the change of the post office name because of a ruling that prohibited naming a post office after a foreign country.

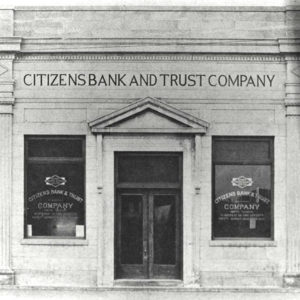

A newspaper, the Arkansas Journal, and a Baptist church soon followed. With the town formally established, merchants and industrialists began making improvements. A cotton gin was built in 1893 and another in 1895. By 1898, England had its own printing press and bank, located in the newly renovated business district of the town.

Early Twentieth Century

In 1902, a farmer named William H. Fuller moved to Lonoke County and began experimenting with planting rice that he had brought from Louisiana. Within the decade, rice became a major cash crop of the Grand Prairie, and a mill was built in 1913 to accommodate the volume of rice being produced in the area. Though rice was well suited to the flat, poorly drained land, cotton continued to be the biggest cash crop of the area.

In 1917, an African American man named Sam Cates was lynched near England for allegedly harassing white girls and women.

The Drought of 1930–1931 devastated the rural population of England. Cotton production and prices fell dramatically, and many families were left with no food for the winter. When help from the Red Cross finally arrived, it was not enough for all of those in need. By the end of December 1930, ration forms had run out, and the Red Cross began turning away hungry families. A tenant farmer named H. C. Coney and forty-seven other farmers drove into England to demand relief. When they were told to wait on relief from the Red Cross by mayor Walter O. Williams and the chief of police, the farmers decided to wait in front of a local grocery store. A crowd of more than 300 soon gathered to demand food, which Red Cross officials were not able to provide because they had no extra ration forms. With the crowd growing more restless, local merchants began distributing food with the promise that the Red Cross would pay them back. Though no actual violence occurred, this event came to be known as the England Food Riot and sparked national debate about the need for a fairer distribution of goods in times of crisis. Cowboy humorist Will Rogers traveled the country around England, visiting the afflicted farmers and raising money for their relief. After the passing of the Agricultural Adjustment Act as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the federal government intervened to reduce the production of cotton, helping the agriculturally based economy of England and many small towns like it that had suffered through the Depression.

World War II through the Modern Era

In the late 1940s, soybeans, which were cheaper and more environmentally friendly to produce, were introduced to the area. Soybean production diversified farming, though it did not replace cotton and rice. As these new crops thrived in the rich Delta soil, new technology was introduced to clear land that was previously too wet to farm. This sparked criticism from environmentalists that farmers were misusing and polluting the land. The 1985 Farm Bill instituted the Conservation Reserve Program, which, along with its successive incarnations, has impacted many England farmers by limiting crop production to control soil erosion, protect wildlife habitats, and improve water supply and quality.

England schools were not desegregated until the 1970–71 school year. That same fall, the England Academy was opened in the city, but it closed after several years due to financial difficulties. The city’s youth baseball program did not admit African Americans until 1983. According to a 1990 article in the Arkansas Gazette, the high school cheerleading squad had no African-American members in the 1980s until 1986, when the squad was told to accept a representative number of African Americans rather than accepting only white students. Then, as is the case in the early twenty-first century, the city and the school were both about sixty-five percent white.

In 1990, a fight between two students at England High School—one white and one black—erupted into a racial conflict as more students began to accumulate, ending with about 250 students involved in the confrontation and one student claiming he had been choked by the chief of police. The next day, only 150 of the school’s 480 students attended class, as a group of black parents calling themselves the United Citizens boycotted the school. During the next few days, the Ku Klux Klan distributed inflammatory leaflets to houses in the city. This brought national attention to the town. Governor Bill Clinton met with an integrated group of parents, advising them to create a biracial committee to work out their problems. The committee was successful in defusing the tension, and this incident was cited by many as proof of Gov. Clinton’s ability to unite people during his campaign for president in 1992.

The decline of the farming industry has had a major impact on England. Many farmers went bankrupt or moved away as the investments needed to maintain a farming operation became too great. In 1993, the city began holding an annual Fluff N Feather Fest in the fall to draw attention to the farming industry of the area, but poor management and lack of interest scuttled the venture after a few years. The highlight of the festival was the duck race.

In the twenty-first century, England has seen some potential for industrial growth. In 2007, Arkansas senators Blanche Lincoln and Mark Pryor, along with U.S. Representative Marion Berry, announced that they had secured a $2.1 million loan from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Development Program for the construction of a new water treatment plant in England that would serve Lonoke County. City leaders were presented with a $1.3 million community development block grant the same year to fund improvements to England’s industrial park in anticipation of the building of a manufacturing facility by England OilField Services, which brought 175 jobs and a $10 million investment to the city.

Attractions

The Wagon Yard Museum is a privately owned collection of wagons, stage coaches, and farm equipment. The museum also features a replica of the original Bank of England, a pioneer church, a school, and three cells from the original England jail.

Famous Residents

Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton, the first black player to sign a contract with the National Basketball Association (NBA), lived in England before his family moved to Chicago, Illinois, when he was eight years old. Clifton’s nickname came from his love of soft drinks as a boy. Clifton played both basketball and baseball professionally and became the oldest player to be named an NBA All-Star. Dancer and choreographer Lula Washington was born in England in 1950. Initially rejected at the University of California–Los Angeles (UCLA) school of dance because of her age, she appealed the decision, succeeded in the school’s dance program, and, after graduation, opened a highly regarded dance company in Los Angeles. Bill Foster served in the state legislature for over three decades beginning in the early 1960s. Cone Magie helped pioneer community journalism and furthered the interest of tourism in Arkansas.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Central Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1889.

City of England. http://www.cityofengland.org (accessed May 28, 2022).

McGhee, Gladys. “The Growth and Development of England, Arkansas.” MSE thesis, University of Central Arkansas, 1958.

McGraw, Shirley, and Carol Bevis. Lonoke County, Arkansas: A Pictorial History. Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co., 1998.

Young, R. L. History of Lonoke County, Arkansas. England, AR: Citizens Bank & Trust Co., 1923.

Catherine Henderson

Ward, Arkansas

Staff of the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture

Oil Industry

Oil Industry England

England  England Bank

England Bank  England Cotton Fields

England Cotton Fields  England Democrat

England Democrat  England Depot

England Depot  England Depot

England Depot  England Fire Department

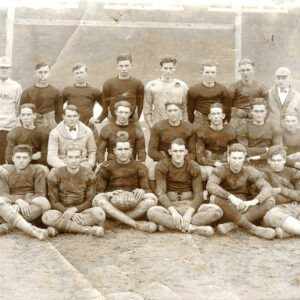

England Fire Department  England Football Team

England Football Team  England High School

England High School  England School

England School  England Schools

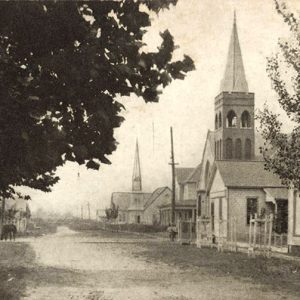

England Schools  England Street Scene

England Street Scene  England Street Scene

England Street Scene  England Street Scene

England Street Scene  England Water Tower

England Water Tower  Lonoke County Map

Lonoke County Map

There were several African-American cheerleaders between 1972 and 1975. I believe they were Opal Sims, Cassandra Dodson, Gloria Mahomes, Phylis Nichols, and Valerie Baker.