calsfoundation@cals.org

Brinkley (Monroe County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º53’16″N 091º11’40″W |

| Elevation: | 208 feet |

| Area: | 5.69 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 2,700 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | August 31, 1872 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

327 |

1,510 |

1,648 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,740 |

2,714 |

3,046 |

3,409 |

4,173 |

4,636 |

5,275 |

4,909 |

4,234 |

3,940 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3,188 |

2,700 |

The town of Brinkley in Monroe County sits just south of Interstate 40, halfway between Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Memphis. In addition to being a center for railroad traffic and agriculture, Brinkley has become known for its recreational opportunities, which include hunting, fishing, hiking, and boating. Since 2004, Brinkley has also associated its image with the ivory-billed woodpecker, which was seen in the nearby Dagmar Wildlife Management Area.

Early Statehood through Reconstruction

In 1852, the state of Arkansas presented a land grant in the northern part of Monroe County to the Little Rock and Memphis Railroad Company, an enterprise promoted by Robert Campbell Brinkley, a leading resident of Memphis, Tennessee. The community was incorporated in 1872 and named for this early pioneer, who was president of the railroad company, president of Planters Bank of Memphis, and an entrepreneur in westward development.

Brinkley was platted in the winter of 1869–1870. Situated at the highest point between Crowley’s Ridge and the west side of the White River at DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), the community grew from a campsite called Lick Skillet that was used by the railroad’s construction workers. Legend has it that when the day’s work was completed, the railroad crew cooked dinner over a campfire and retired for the evening only when the last “skillet was licked.”

Construction of the rail lines between Memphis and Little Rock brought the city of Brinkley into being, but the accomplishment was not without challenges. In 1862, when the railway advertised the opening of the route, seventeen miles between DeValls Bluff and Brinkley had to be negotiated by boat or stage via Clarendon (Monroe County)—sixteen miles by stage, when possible, and thirty-five miles by boat, a trip of five to six hours depending upon weather. But after the completion of the bridge across the White River in 1871, the two portions of the line were connected.

Brinkley grew from its railroad backbone. In the late 1870s, taking advantage of the town’s railroad connections, Major William Black of Memphis moved to Brinkley and established a sawmill south of town in partnership with Memphian John Gunn. (Black had served in the Confederate army and participated in many of the battles in and around Memphis.) Later, Black and Gunn founded the Brinkley Car Works and Manufacturing Company, the first manufacturing concern in town. Gunn and Black were responsible for constructing parts of the Little Rock and Memphis and the Cotton Belt rail lines. They laid a line north from Brinkley to haul logs to their mills. This rail line eventually was extended and became the Brinkley and Batesville line, later purchased by Rock Island. The railroad they built southward from town became part of the Arkansas Midland, which provided service to Helena (Phillips County). Gunn also established the John Gunn Grocery Company, a wholesale business that was one of the largest mercantile institutions in east Arkansas.

Brinkley’s first store was the M. B. Park Company, operated by Mathew B. Park and Hilliard A. Carter, formerly merchants from Clarendon. Sam Hoskins was the first mayor, and the Reverend Thomas H. Howard preached the first sermon and organized the Methodist church, both in 1870. Moses Guthrie and William Munn were among the early settlers in the area, along with Alexander White, Robert H. Letson, A. S. Livermore, Albert G. DeShon, and Michael Kelly.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The Cotton Belt Hotel, built in 1883 by Colonel James W. Savage, was the town’s first hotel. James J. Farrell installed the town’s first electric plant in 1896. Farrell also founded the Brinkley Locomotive Works and operated a gin and a lumber plant.

The railroads facilitated the rapid export of lumber and lumber products from area sawmills, stave mills, and related industries. Brinkley developed as a pivotal crossroads in east Arkansas, halfway between Memphis and Little Rock, with railroads leading in all directions. The town increased in size from 325 people in 1880 to 1,648 in 1900.

Brothers Robert J. and B. F. Kelley, along with J. C. McKetham, established the Brinkley Argus in 1883. The newspaper was sold in 1891 to William B. and Harriet Folsom. It is still in publication.

By the 1890s, Brinkley’s business district included several mills, factories, and shops. Land surrounding Brinkley was used for farming. As the densely wooded land was cleared, cotton cultivation began, and cotton gins and compresses were established. Besides cotton, rice cultivation became a major economic factor in the early 1900s. In the early 1890s, the business district was rebuilt after fire destroyed it.

Notable educational opportunities for African Americans in the area included the Consolidated White River Academy in the late 1800s and Fargo Agricultural School in the early 1900s. However, hostility toward Black residents could manifest itself violently, as with the lynching of Godfrey Gould on July 30, 1896.

Early Twentieth Century

On November 8, 1903, a white man named Zallie C. Cadle was lynched for allegedly murdering a night marshal. Brinkley’s greatest disaster struck on March 8, 1909, when a tornado destroyed much of the town, killing about sixty people and injuring hundreds. Only a church and about fifteen of the city’s nearly 1,000 homes were left standing. Governor George Washington Donaghey declared martial law in Brinkley. The State Guard from Helena and McCrory (Woodruff County) was called in, and 150 convicts were brought in to help clean up the area. Mayor Thomas Henry Jackson set up a temporary office in a tent.

The city rebounded and rebuilt homes, businesses, and infrastructure. In 1912, Brinkley was honored when President Theodore Roosevelt stopped there and gave a short speech about the Progressive Party movement to a crowd of about 500. Brinkley hosted a Navy recruitment party in December of 1917, as Monroe County sought to recruit 1,000 volunteers to assist the nation in fighting World War I.

During the Depression, residents of Brinkley struggled, as did most Arkansans. During this time, Brinkley served as a crossroads for reaching residents of east Arkansas. In August 1932, it was a stop for the “Kingfish of Louisiana,” Huey P. Long, who was campaigning on behalf of Hattie Caraway of Arkansas. They spoke at Brinkley City Park.

World War II through the Modern Era

From the 1950s through the 1970s, industry expanded with the establishment of production plants operated by Phillips Van Heusen and Wagner Electric Corporation. Today, many Brinkley businesses are farm related. The primary industry and employer is Riviana Foods, which processes rice. The opening of Interstate 40 in 1967 led to the decline of downtown businesses. The highway made it far easier for Brinkley residents to travel to Little Rock or Memphis for shopping and entertainment.

Brinkley was not one of the first communities in Arkansas to desegregate its schools, but like the rest of Monroe County it participated in desegregation without major upheaval. For a period in the 1960s, Monroe County schools experimented with “open choice,” but Brinkley schools, as well as all others in the county, were fully desegregated by the 1970–71 school year.

At the end of the twentieth century, Brinkley needed a new focus, as the railroads and agricultural interests were no longer guaranteeing the strength of the community. Increasingly, Brinkley promoted its availability for recreation and tourism. Hunting, fishing, hiking, and boating all have been stressed as opportunities near Brinkley. Bird watching was added to the list when an ivory-billed woodpecker—thought to have become extinct sixty years earlier—was sighted near Brinkley in 2004.

Famous Residents

Louis Thomas Jordan, “the father of rhythm and blues,” was born in Brinkley in 1908. The singer, saxophonist, and bandleader traveled the world performing in concerts and on radio and television. Movie producer Plato Skouras and his wife, Barbara (a Brinkley native), ran a restaurant in Brinkley until his death in Brinkley in 2004.

Attractions

The Central Delta Depot Museum, run by the Central Delta Historical Society, is open to the public. Brinkley is home to the Great Southern Hotel, a historic building listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Ellis and Charlotte Williamson House was designed by architect Frank L. Doughty and is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

For additional information:

Hanley, Ray. “The Brinkley ‘Cyclone.'” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 2, 2022, pp. 1H, 6H. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/jan/02/the-brinkley-cyclone/ (accessed September 12, 2022).

———. “Death Wind Blows Across the Grand Prairie of Arkansas.” Central Arkansas Historical Journal 1 (February 1997): 10–19.

Sayger, Bill. A Brinkley Remembrancer. 2 vols. Brasfield, AR: 2002 and 2003.

Jane Dennis

Little Rock, Arkansas

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Arlington Hotel

Arlington Hotel  B&A Motel

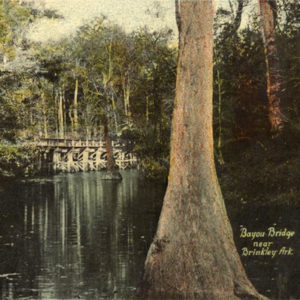

B&A Motel  Bayou Bridge

Bayou Bridge  Entering Brinkley

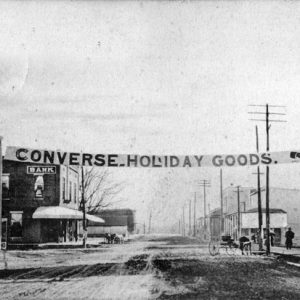

Entering Brinkley  Brinkley Street Scene

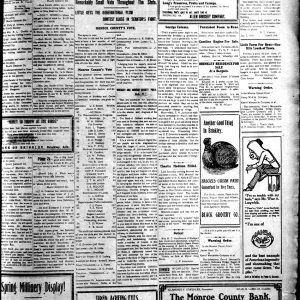

Brinkley Street Scene  Brinkley Argus

Brinkley Argus  Brinkley Church

Brinkley Church  Brinkley Church

Brinkley Church  Brinkley Cyclone Damage

Brinkley Cyclone Damage  Brinkley Electrification

Brinkley Electrification  Brinkley Fire Station

Brinkley Fire Station  Brinkley Fire Station

Brinkley Fire Station  Brinkley High School

Brinkley High School  Brinkley Jail

Brinkley Jail  Brinkley Library

Brinkley Library  Brinkley Post Office

Brinkley Post Office  Brinkley School

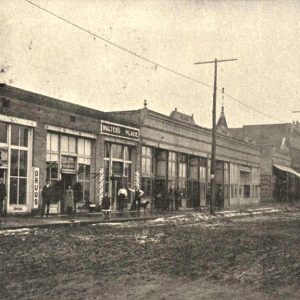

Brinkley School  Brinkley Street Scene

Brinkley Street Scene  Brinkley Street Scene

Brinkley Street Scene  Brinkley Street Scene

Brinkley Street Scene  Brinkley Street Scene

Brinkley Street Scene  Brinkley Street Scene

Brinkley Street Scene  Brinkley Street Scene

Brinkley Street Scene  Brinkley Water Tower

Brinkley Water Tower  Central Delta Depot Museum

Central Delta Depot Museum  Church Destroyed

Church Destroyed  Consolidated White River Academy

Consolidated White River Academy  Cypress Street

Cypress Street  Douglass Store

Douglass Store  First Missionary Baptist

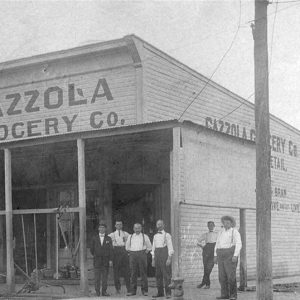

First Missionary Baptist  Gazzola Grocery

Gazzola Grocery  Great Southern Hotel

Great Southern Hotel  Hotel Rusher

Hotel Rusher  Ivory-billed Woodpecker

Ivory-billed Woodpecker  Lake Greenlee

Lake Greenlee  Lake Greenlee Sign

Lake Greenlee Sign  Monroe County Map

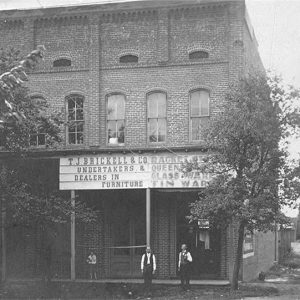

Monroe County Map  T. J. Brickell & Co.

T. J. Brickell & Co.  Veterans Memorial

Veterans Memorial  World War I Soldiers

World War I Soldiers

Monroe County also had several rural schools in the late 1800s. There were Allendale, Banner, Blackton, Bethelam, and Monroe.