calsfoundation@cals.org

Fort Smith (Sebastian County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º23’09″N 094º23’54″W |

| Elevation: | 446 feet |

| Area: | 63.99 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 89,142 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | December 24, 1842 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

964 |

1,532 |

2,227 |

3,099 |

11,311 |

11,587 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

23,975 |

28,870 |

31,429 |

36,584 |

47,942 |

52,991 |

62,802 |

71,626 |

72,798 |

80,268 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

86,209 |

89,142 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fort Smith shares its status with Greenwood as the county seat of Sebastian County. Early in the history of Arkansas and the city, Fort Smith was an important point of contact to the American West. It is now home to large manufacturing plants; St. Edward Mercy Medical Center and Baptist Health-Fort Smith, which provide healthcare to residents beyond the confines of the city; and the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith. Fort Smith was for a long time the second-largest city in Arkansas after Little Rock (Pulaski County) but, after the 2020 census, was ranked the third-largest, with Fayetteville (Washington County) now the second.

Pre-European Exploration

No indigenous peoples appear to have had permanent settlements at the time of European contact in what became Fort Smith. In southern Fort Smith, a platform mound commonly called the Cavanaugh Mound exists in isolation and may have provided a vantage point from which the Spiro Mounds in present-day Oklahoma could have been seen in an earlier century.

European Exploration and Settlement

Hernando de Soto’s expedition into Arkansas in 1541 may have reached as far west as Fort Smith. Place names in eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas—Poteau, Belle Point, and Massard Prairie—give some evidence of the presence of French trappers and others who perhaps used the Arkansas River and its tributary, the Poteau River. The Arkansas River Valley provided fertile bottom land to earlier farmer settlers. Belle Point, a river bluff, along the Arkansas River just north of its juncture with the Poteau, afforded an excellent vantage point looking west and a defensible position for the first Fort Smith military post.

Louisiana Purchase and Early Statehood

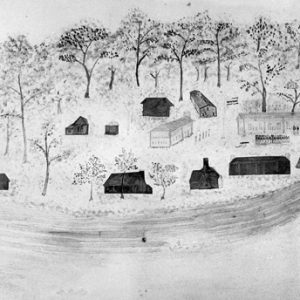

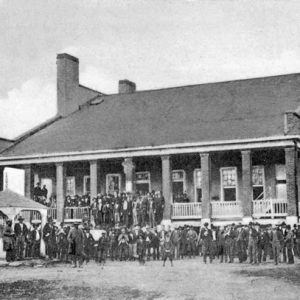

In November 1817, the first American troops arrived at Belle Point and began building the first structures. The principal purpose of the fort was to keep the peace between the Osage and Cherokee tribes that had entered the area, as was the Fort Smith Council, a meeting held between Indian and territorial leaders in 1822. Around the fort, a small settlement began forming, taking its name from the fort that, in turn, was named for General Thomas A. Smith, the military district’s commander. In 1822, John Rogers first arrived in the town and established himself as a supplier to the fort and trader with trappers, Native Americans, and other settlers. The army abandoned the fort and moved west to establish Fort Gibson in the Indian Territory (later Oklahoma). In the 1830s, the U.S. Congress funded several military roads, including Fort Smith to Jackson Road, to improve transportation in territorial Arkansas. By 1836, the army returned and began building the second Fort Smith military post. Rogers lobbied successfully for the military’s return. Because of his strong association with both forts and his early efforts to promote the town, many consider him to be the founder of the city of Fort Smith.

Fort Smith was an important center for outfitting forty-niners during the gold rush in late 1848 and early 1849, as well as soldiers in the Mexican War from 1846 to 1848. Although more forty-niners probably disembarked from Missouri for California seeking to stake claims to sources of gold, one of the first wagon trains of those journeying by land left from Fort Smith. This was primarily because the more southern route west from Fort Smith had fresh grass earlier in the spring than the more northerly route. St. Andrew’s College was established in 1849 but it did not last past 1860.

The fort served as an important place for outfitting and supplying military companies. Fort Smith also became increasingly central to communications on the frontier and beyond as stage, steamboat, and mail transportation networks matured.

Civil War through Reconstruction

With the secession crisis following the election of Abraham Lincoln as president in 1860, the Department of War prepared to abandon Fort Smith. Federal troops remained until just before Arkansas seceded, and the commander viewed his military position as untenable. Arkansas volunteers and Confederates took control of the fort shortly after its abandonment. Union forces returned permanently to occupy the garrison in September 1863. Although they continued to hold the fort, Union forces’ hold on the surrounding countryside became increasingly tenuous in 1864 as bushwhackers and Confederate regular and irregular forces marauded and conducted raids on Union forces and their supporters.

Encounters that took place in this area, all in 1864, include an action at Fort Smith in July, an affair at Fort Smith in September, and the Fort Smith Expedition in September and October.

After the war, Federal forces out of Fort Smith worked to restore order to the countryside and rural areas of western Arkansas. Military farm colonies were established in an effort to help refugees become self-sufficient. The city also was the site of the Fort Smith Conference of 1865, a gathering of federal and tribal representatives for the purpose of negotiating the terms under which the former Confederate Indian nations could resume their relationship with the United States.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

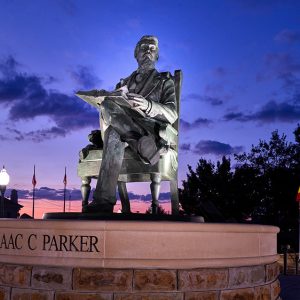

After fires destroyed officers’ quarters at the fort in 1870, the federal government officials initially resolved to sell it but later decided to move the Western Arkansas Federal District Court from Van Buren (Crawford County) to the land at Belle Point. Judge William Story presided over the court but was replaced in May 1875 by Judge Isaac C. Parker, a former congressman from Missouri. Parker’s judgeship lasted until just before his death in 1896 and marks one of the most celebrated periods in Fort Smith history. U.S. marshals and deputy marshals headquartered in Fort Smith not only enforced the law in western Arkansas but also in the frequently lawless neighboring Indian Territory.

In the city of Fort Smith, the late nineteenth century marked a period of booming growth in the 1880s in which the population nearly tripled, commercial trading expanded, and Garrison Avenue became the wholesale and retail center of the region. Railroad transportation arrived in the 1870s, giving the city an important alternative to the Arkansas River.

In 1890, the county purchased land near Fort Smith for the establishment of a poor farm. Only the Elmwood Poor Farm Cemetery remains of this. In early 1898, a tornado tore through Fort Smith, killing more than fifty people.

Early Twentieth Century

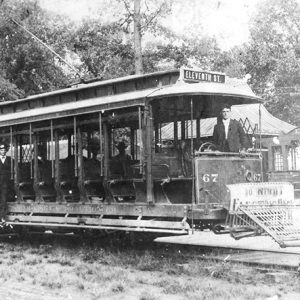

Much of the city’s history until the onset of the Great Depression is a story of the growth (albeit in fits and starts) of its economy and culture. An electric streetcar network within the city grew as the city did. Between 1907 and 1924, the city became one of the few in U.S. history to not only legalize but also regulate prostitution in a restricted district (known as “the Row”).

Fort Smith never had the sizeable African-American communities that Little Rock and other cities in the state had, but Jim Crow came to it nevertheless. Streetcar lines, public bathrooms, water fountains, and other public facilities separated black and white citizens of the city. Howard Elementary School and Lincoln High School provided public education to the city’s black children. Too, on March 23, 1912, a mob of almost 1,000 lynched Sanford Lewis, an African American accused of shooting a constable; however, unlike many cases of lynching in Arkansas, and across the South, several police officers were tried and convicted for failing to stand against the mob.

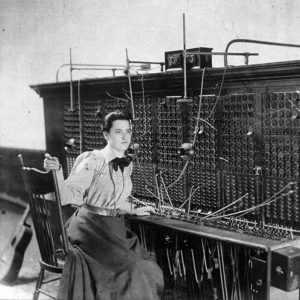

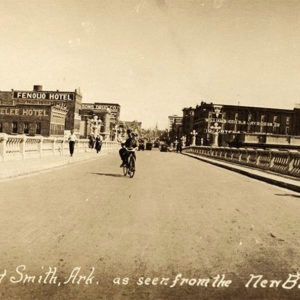

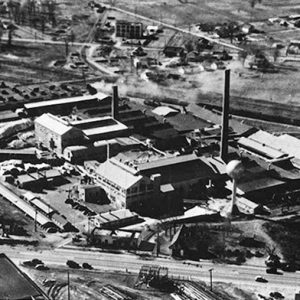

Natural gas was discovered in the area in 1887 and became an important feature that later attracted some manufacturers to the city, namely a notable glass-manufacturing industry. Furniture manufacturing also became increasingly central to the metropolitan economy. On September 19, 1917, women employed as telephone operators at Southwestern Bell in Fort Smith began a strike that would last until late December and would spark a general strike that shut down the whole city for nine days. On May 11, 1922, a bridge to accommodate automobile traffic was constructed to span the Arkansas River at the west end of Garrison, connecting downtown Fort Smith to Oklahoma.

During the Great Depression, infamous criminals Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow hid in Fort Smith to elude capture while Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd robbed and did the same in nearby Oklahoma. The New Deal brought public works projects to the area, and federal workers built a dam in Crawford County to create a water source for the city called Lake Fort Smith.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Camp Chaffee, later renamed Fort Chaffee, was activated as an army base on March 27, 1942. During World War II, Chaffee was used for training armored divisions of the U.S. Army. The army built three prison compounds covering about fifty-three acres of the camp to house 3,400 German prisoners of war. Although Chaffee was well outside Fort Smith’s city limits, it was nearby in Sebastian County, and economic ties between it and the city were strong. After the war, it was deactivated and activated many times. In the 1950s and 1960s, the city struggled and succeeded in diversifying its economy, or at least making it less reliant on Fort Chaffee. KFSM, the state’s second television station, went on the air in Fort Smith in 1953.

On February 1, 1962, the Norge Company opened a factory for the manufacture of refrigerators, freezers, and air conditioners. It was purchased by the Whirlpool Corp. in 1968 and expanded. Hometown companies like Baldor Electric Co.—a maker of motors, drives, and generators—and ABF Freight System Inc.—a less-than-truckload carrier and subsidiary of Arkansas Best Corp.—also are major employers in the city and drivers of the local economy. Many of them can trace their origins back to the period of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

Social change came with economic growth. Fort Smith sought to avoid the divisive integration struggle that Little Rock underwent, but the slow pace of the process, combined with efforts to retain de facto segregation through the construction of a new school in a predominately white part of town, preserved inequalities.

Modern Era

Fort Smith’s population grew during the 1960s and 1970s, and its manufacturing base deepened. St. Edward Mercy Medical Center (renamed Mercy Fort Smith in 2012) opened in a new hospital facility on what was then the eastern edge of town in 1975. Central Mall, one of the largest indoor shopping malls in Arkansas, opened about twenty blocks to the west along Rogers Avenue.

In 1988, Fort Smith was the site of a major trial in which a twelve-person jury sought to determine the guilt or innocence of fourteen right-wing radicals charged with a variety of crimes, most prominently conspiracy to engage in sedition. After hearing from a total of almost 200 witnesses, the jury found none of the defendants guilty.

As recently as 2004, the Whirlpool plant employed 4,600 people, but subsequent layoffs highlighted threats to the city’s investment in its manufacturing base; by 2011, the company employed only approximately 1,000 people. These challenges, also faced by manufacturers nationwide, have been offset somewhat by the good news of expansions by other resident manufacturers and businesses. However, in October 2011, Whirlpool announced that it would be closing its plant in mid-2012 and relocating production to Mexico and other sites in North America.

Demographically, the city of Fort Smith has become more diverse. In 1975, Fort Chaffee was used as the center for federal resettlement of Vietnamese refugees who fled their country following the fall of Saigon. Many of the Vietnamese stayed in the community. Hispanic immigrants became residents of the city and region in recent years as they have in other parts of the state. Finally, a sizeable Laotian community settled in Fort Smith beginning in the 1980s. Wat Buddha Samakitham, a Laotian Buddhist temple; two Vietnamese Buddhist temples; and Vietnamese Christian churches serve the local Asian population.

Education

The U.S. Supreme Court handed down its Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision in 1954 and its implementation in 1955, but the superintendent of schools in Fort Smith announced he would not begin to do so until 1957. He indicated they would then use a “stairstep” process integrating one grade per year. In 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5–4 split decision in Rogers v. Paul, directed the Fort Smith School Board to desegregate all of its high schools immediately.

Fort Smith public schools today provide education from kindergarten through the twelfth grade, as do some private Protestant schools. Catholic parochial schools offer education through the ninth grade. The University of Arkansas at Fort Smith administers numerous four-year bachelor’s degree programs. Webster College and Siloam Springs–based John Brown University (JBU) also operate four-year programs through satellite facilities in Fort Smith.

Industry

Manufacturing, trucking, and food-processing sectors employ thousands of people in the Fort Smith economy. The city is home to Baldor Electric’s motor and drive factory and Hiram Walker’s blending and bottling facility. Fort Smith remains an important hub for shopping and consumers in the city and region. Fort Smith’s hospitals and university also are major employers.

Attractions

What remains of the buildings at the second Fort Smith military post today house the exhibits of the Fort Smith National Historic Site. Miss Laura’s Social Club, a former brothel and the only remaining building from the Row, is home to the city’s Convention and Visitors Bureau and the only former house of prostitution on the National Register of Historic Places. Many of the homes in original Fort Smith today also are on the register and form the city’s Belle Grove Historic District. The Fort Smith Historical Society was formed in 1977 and is still active four decades later, operating out of the Fort Smith Museum of History. The Fort Smith Regional Art Museum is housed in the Vaughn-Schaap House within this district. In 2006, on land formerly a part of Fort Chaffee, the Janet Huckabee Arkansas River Valley Nature Center was opened to educate visitors to the natural environment of the state and the western Arkansas region in particular. In 2023, the U.S. Marshals Museum opened in Fort Smith.

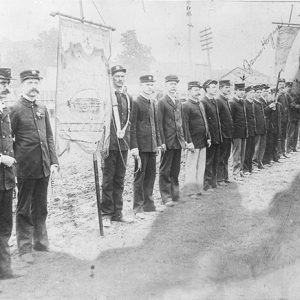

The Fort Smith National Cemetery is the oldest of the state’s three national cemeteries. Fort Smith also boasts a Spirit of the American Doughboy monument to World War I veterans and the St. Scholastica Monastery for Benedictine nuns (although the historic monastery building has been demolished). A Confederate monument stands on the grounds of the Sebastian County Courthouse. The Fort Smith Regional Airport is a mixed-use airport located three miles outside of town. Reportedly the oldest continually operating eatery in Fort Smith, Ed Walker’s Drive-in and Restaurant is a classic diner and the only restaurant in the state with curbside beer service.

Famous Residents

Fort Smith has had many residents of note. They include: American explorer Benjamin Bonneville; activists Katharine Susan Anthony and Mame Stewart Josenberger; judges Thomas Hadden Humphreys and Bernice Lichty Parker Kizer; executioner George Maledon; military veterans John Pearson Jr., William O. Darby, William Bradford, Charles Cook, Wendel Archibald Robertson, and Paul Wolfe; career ambassador Anne Patterson; and twelfth president of the United States Zachary Taylor, who was stationed briefly at the fort.

William H. H. Clayton was an important figure in the history of the state during Reconstruction; his home was turned into a museum. Edward Walter Eberle was a Navy officer who had two naval ships named in his honor. Henry Champlin Lay was a missionary bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Arkansas. Elias Rector DuVal was a physician who pushed to modernize medicine in Arkansas. Harry Pelot McDonald was a doctor, leader, and civil rights activist in the second half of the twentieth century.

Additional notable figures include: newspaperman John Carnall; pioneer woman attorney Kathryn Van Leuven; writers Thyra Samter Winslow and Speer Morgan; musician Alphonso Trent; sculptor Robyn Hutcheson Horn; filmmaker Marty Stouffer; and actors Laurence Luckinbill and Rudy Ray Moore. John Boozman, a leading Republican in the twenty-first century, attended high school in Fort Smith.

For additional information:

Atkins, Jerry. Hangin’ Times in Fort Smith: A History of Executions in Judge Parker’s Court. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2012.

Bearss, Edwin C., and Arrell M. Gibson. Fort Smith: Little Gibraltar on the Arkansas. 2nd ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979.

Bledsoe, Wayne, John Lehnen, and Jim Kreuz. Stained Glass, Chalk Boards and Cash Registers of Fort Smith, Arkansas. N.p.: 2021.

Boulden, Ben. The Hidden History of Fort Smith, Arkansas. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012.

Carson, Adam. “Beyond Boosterism: Fort Smith and the Creation of a Conservative Economic Culture.” In Reconsidering Southern Labor: Race, Class, and Power, edited by Matthew Hild and Keri Leigh Merritt. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018.

———. “Feet in the South, Eyes to the West: Fort Smith Enters the Sunbelt.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2013. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/737/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Faulk, Odie B., and Billy Mac Jones. Fort Smith: An Illustrated History. Muskogee, OK: Western Heritage Books, 1983.

Glenn, Shirley. The Law West of Fort Smith: A History of Frontier Justice in the Indian Territory, 1834–1896. New York: Collier Books, 1961.

The Goodspeed Histories of Sebastian County, Arkansas. Columbia, TN: Woodward & Stimson Printing Co., 1977.

Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society. Fort Smith, AR: Fort Smith Historical Society (1977–).

Kreuz, Jim, and John Lehnen. Homes with History: Fort Smith, Arkansas. N.p.: 2023.

Kreuz, Jim, and Wayne Bledsoe. Treasures of Fort Smith. N.p.: 2019.

Prewitt, Taylor. Before It Got Complicated: Medicine in Fort Smith and the Arkansas River Valley, 1817–1975. Fort Smith, AR: Red Engine Press, 2023.

Schmidt, Kyra. “Hello Girls on Strike: Telephone Operators, the Fort Smith General Strike and the Struggle for Democracy in Great War Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2020.

Weaver, J. F., and W. J. Weaver. “Early History of Fort Smith.” Unpublished typescript. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Benjamin Boulden

Fort Smith Historical Society and Fort Smith Museum of History

Adams Express

Adams Express  Andrews Field

Andrews Field  Katharine Anthony

Katharine Anthony  Belle Grove Street Scene

Belle Grove Street Scene  Belle Grove Street Scene

Belle Grove Street Scene  Belle Point Hospital

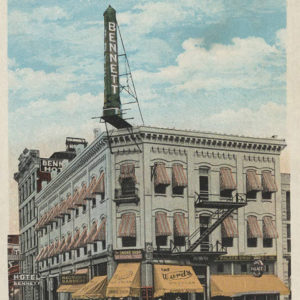

Belle Point Hospital  Bennett Hotel

Bennett Hotel  Buddhist Temple

Buddhist Temple  Carnall Statue

Carnall Statue  Carnegie Library Groundbreaking

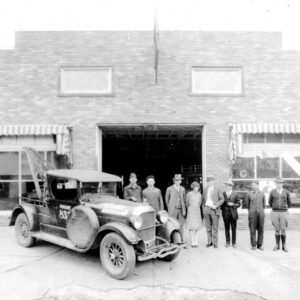

Carnegie Library Groundbreaking  Cates Motor Service

Cates Motor Service  Dredge Boat

Dredge Boat  Ed Walker's Drive-in and Restaurant

Ed Walker's Drive-in and Restaurant  Electric Park Pavilion

Electric Park Pavilion  Fort Smith; 1890s

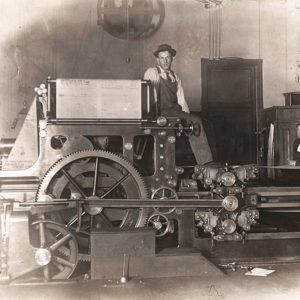

Fort Smith; 1890s  Fort Smith Switchboard

Fort Smith Switchboard  Fort Smith Trolley

Fort Smith Trolley  Fort Smith in 1836

Fort Smith in 1836  Fort Smith Fire Department

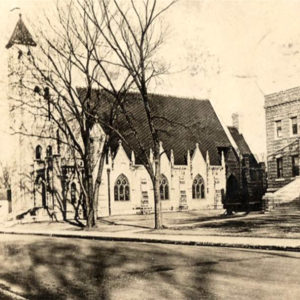

Fort Smith Fire Department  Fort Smith Catholic Church

Fort Smith Catholic Church  Fort Smith Courthouses, 1896

Fort Smith Courthouses, 1896  Fort Smith Drawing

Fort Smith Drawing  Fort Smith Federal Courthouse

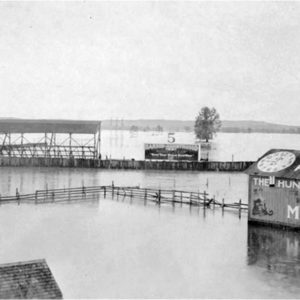

Fort Smith Federal Courthouse  Fort Smith Flood

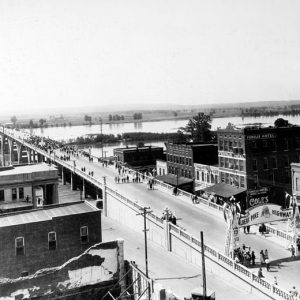

Fort Smith Flood  Fort Smith Free Bridge

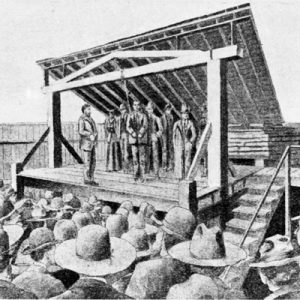

Fort Smith Free Bridge  Fort Smith Hanging

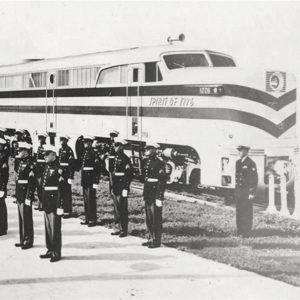

Fort Smith Hanging  Fort Smith Locomotive

Fort Smith Locomotive  Fort Smith Museum of History

Fort Smith Museum of History  Fort Smith National Cemetery

Fort Smith National Cemetery  Fort Smith National Cemetery

Fort Smith National Cemetery  Fort Smith National Historic Site

Fort Smith National Historic Site  Fort Smith Jail

Fort Smith Jail  Fort Smith National Historic Site

Fort Smith National Historic Site  Fort Smith Presbyterian Church

Fort Smith Presbyterian Church  Fort Smith Times Record

Fort Smith Times Record  Fort Smith Tornado

Fort Smith Tornado  Fort Smith Trolleys

Fort Smith Trolleys  Fort Smith Vietnamese Restaurant

Fort Smith Vietnamese Restaurant  Freedom Train

Freedom Train  Garrison Avenue

Garrison Avenue  Garrison Avenue

Garrison Avenue  Garrison Avenue

Garrison Avenue  Goldman Hotel

Goldman Hotel  Harding Glass Plant

Harding Glass Plant  Hotel Main

Hotel Main  KFSM-TV Crew

KFSM-TV Crew  Knoble Brewery

Knoble Brewery  Angus McLeod House

Angus McLeod House  Miss Laura's Social Club

Miss Laura's Social Club  Judge Parker Statue

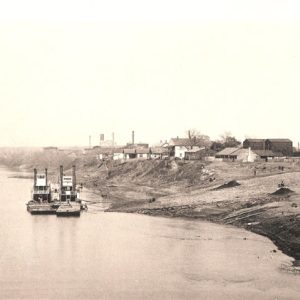

Judge Parker Statue  Poteau River at Fort Smith

Poteau River at Fort Smith  Quinn Chapel

Quinn Chapel  John Henry Rogers

John Henry Rogers  Teddy Roosevelt in Fort Smith

Teddy Roosevelt in Fort Smith  Sebastian County Courthouse, Fort Smith

Sebastian County Courthouse, Fort Smith  Sebastian County Map

Sebastian County Map  Sparks Regional Medical Center

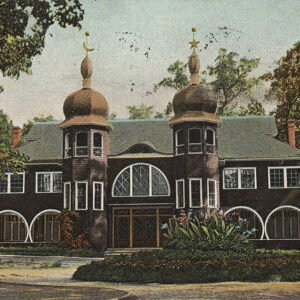

Sparks Regional Medical Center  St. Scholastica Monastery

St. Scholastica Monastery  Belle Starr

Belle Starr  U.S. Marshals Museum

U.S. Marshals Museum  U.S. Marshals Museum Sign

U.S. Marshals Museum Sign  University of Arkansas at Fort Smith

University of Arkansas at Fort Smith

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.