calsfoundation@cals.org

Forrest City (St. Francis County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º00’29″N 090º47’23″W |

| Elevation: | 276 feet |

| Area: | 20.24 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 13,015 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | May 11, 1870 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

903 |

1,021 |

1,361 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

2,484 |

3,377 |

4,594 |

5,699 |

7,607 |

10,544 |

12,521 |

13,803 |

13,364 |

14,774 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15,371 |

13,015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forrest City, located on the western slope of Crowley’s Ridge near the center of St. Francis County, has been a center of commerce and trade since its incorporation in 1870. Serving as the county seat since 1874, the city is named in honor of Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest. It is the only such named city in the world spelled with two Rs.

Pre-European Exploration through Early Statehood

The many Native American artifacts found along the St. Francis River and a number of identified Indian mounds within the county provide evidence that the area was inhabited long before the expedition of Hernando de Soto visited the surrounding area in 1541.White settlers began to be attracted to the high ground on Crowley’s Ridge by the early 1800s. In 1827, the territorial legislature created St. Francis County, and the completion of the Military Road connecting Memphis, Tennessee, and Little Rock (Pulaski County) brought additional settlers.

Civil War through Reconstruction

During the Civil War, five Confederate companies were raised in the county. A number of military events occurred in the county, including the 1862 Skirmish at L’Anguille Ferry and the Skirmish at Taylor’s Creek in 1863. Military forces moved in and out of the area for the duration of the war.

The outbreak of the war interrupted construction of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad, which passed through St. Francis County. Contractors were eager to renew work on the line. Shortly after the war, former Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest obtained a contract with the railroad company to lay tracks across Crowley’s Ridge. In 1866, with approximately 1,000 Irish laborers under his direction, construction began. The founding of Forrest City is traced to the commissary established by Forrest. Local businessman U. B. Izard proposed a survey for a town, and, on March 1, 1869, a thirty-six-block town site was marked off by county surveyor John C. Hill near the old commissary site. The name Izardville was considered, but with the founding of a post office that same year the name of Forrest City was recorded. The town began to develop rapidly. By the end of 1869, the first freight train arrived, and passenger service was available within two years.

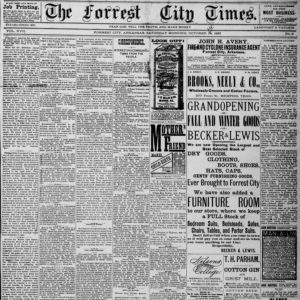

The first mercantile, Izard Brothers and Prewett, was open before 1870. With its connection to the railroad, Forrest City was becoming the commercial center for local cotton farmers. In 1870, the first newspaper, the Forrest City Free Press, was founded, soon followed by the Forrest City Times. In 1877, a third newspaper, the Forrest City Democrat, was established. Further growth prompted incorporation on May 11, 1870, with J. W. Grogan as the first mayor.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

After much resistance and an election in 1874, the county seat was moved from Madison to Forrest City. The citizens of Madison threatened an injunction and refused to release the county records. During the night, the records were secretly removed to Forrest City.

The city was struck by a devastating fire in the winter of 1874, resulting in the destruction of nine buildings and damage to a number of others. Many of the county records were destroyed in the fire.

Recovering from the fire, the city experienced steady growth. The religious community began to grow in the 1870s. A Baptist congregation, which was founded in 1869, was followed by the Methodists in 1871, the Presbyterians by 1875, and the Roman Catholics in 1876. By the 1890s, there were also two African-American Baptist churches and one African-American Methodist church. A public school was also opened in the early 1870s with an impressive brick school house constructed in the early 1890s. The Crowley’s Ridge Institute, which offered instruction from the primary grades to high school, was also in operation by the 1890s. In less than ten years from incorporation, the population topped 900.

Tragedy struck the city again during the fall of 1879 with a yellow fever outbreak. Before the end of October, thirteen people had died and the city was quarantined.

In 1889, violence erupted in what has been called the Forrest City Riot. Four people were killed before a dispute between Black and white voters over a school board election was settled. The event, which received national media coverage, resulted in several Black officials being driven from the city.

Early Twentieth Century

By the early 1900s, the city had established a water and sewer system, there were electric street lights, and several of the city streets were paved. Additional investment money was made available by the opening of the Planters Bank in 1910. This bank, the city’s second, followed the Bank of Eastern Arkansas founded in 1886.

Three African American men have been lynched in or near Forrest City. In 1902, Charles Young was burned to death just outside of town. In 1911, Nathan Lacey was lynched, followed in 1919 by Sam McIntyre.

By 1920, the population had reached almost 3,400, and Forrest City was home to three banks, a fire department, a cotton compress, a cotton seed oil mill, an ice factory, and other businesses. In 1927, a public library was founded. A number of women’s clubs—including the Musical Coterie, the Nathan Bedford Forrest Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and the Delphian Club—were founded in the 1920s. The city’s first women’s club, the Cosmos Club, had been in existence since 1899.

Much of the area was inundated during the Flood of 1927. One of the county’s three Red Cross relief camps was established on the high ground at Forrest City. The camp was the largest in the state, providing basic necessities for 15,000 refugees. The area was hit hard by the Great Depression and the Drought of 1930–31, with fifty percent of the county’s farmers receiving government aid. Commerce received a boost with the completion of the St. Francis River Bridge east of Forrest City on September 4, 1933. Again in the Flood of 1937, Forrest City served as an important Red Cross camp for refugees.

World War II through the Modern Era

Recovery from the Great Depression was slow. During World War II, many of Forrest City’s young men served overseas. By the late 1940s and early 1950s, the city began to experience significant economic growth. The area was an attractive site for industrial growth due to its railroad connections and U.S. Highway 70 connecting to Memphis. Shortly after World War II, an industrial plant was established by the city government, with Forrest City Machine Works being the first industry to build. The opening of the Hamilton Moses Power Plant in 1951 four miles west of Forrest City stimulated growth, as did the construction of Interstate 40. Even before its completion in the 1960s, the city began to expand toward the highway. The Industrial Development Corporation, founded by the state in 1955, promoted Forrest City as a location for industry. The corporation’s first major achievement was the location of the Yale and Towne factory at Forrest City. A city planning commission to direct the growth was founded in 1957.

Forrest City continued to grow in the 1960s. The school district, which desegregated in 1964, was the largest consolidated district in the state by the 1960s. A modern hospital, Forrest Memorial, opened, as did a municipal airport in 1960. By 1962, the city sported five municipal parks.

During the 1960s, the city played a role in the civil rights movement as one of three Delta communities to serve as a headquarters for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a national civil rights organization. The quality of the schools quickly became an issue. In September 1965, ninety percent of the Black student body staged a school boycott protesting the conditions; approximately 200 protesters were arrested. Four years later, a boycott of white-owned businesses and a march on Little Rock was organized to protest the firing of a Black teacher by the all-white school board. By 2010, the Black population of the city was about sixty-seven percent.

Crowley’s Ridge Technical Institute opened in the 1960s and provided technical and vocational training. In 1974, East Arkansas Community College opened its doors. The two institutions operated alongside each other until their merger in 2017.

In 1979, Sanyo Manufacturing, a Japanese electronics firm, bought a plant in Forrest City at which it manufactured television sets. The company initially established good relations with the union representing its workers, most of whom were African American, but in 1985 the company proposed a wage reduction, which inaugurated a bitter strike. The company employed 2,000 at the height of its operations but had downgraded that to 500 employees by the time it closed the Forrest City plant in 2016.

Agriculture continues to drive the local economy. Still, almost one-third of the city’s population falls below the national poverty level.

Attractions and Famous Residents

Recreational attractions in the area include Village Creek State Park. The L’Anguille and St. Francis rivers are popular fishing steams. Several structures in Forrest City are included on the National Register of Historic Places; one, the Rush-Gates Home, is the site of the St. Francis County Museum.

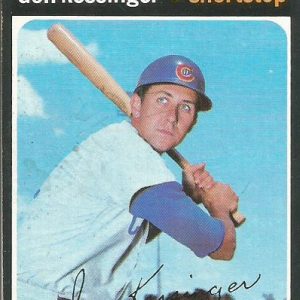

Famous residents include Mark Whitaker Izard, the second territorial governor of Nebraska. Josiah Homer Blount was a local businessman and educator who was the first African American to run for governor of Arkansas. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member Al Green was born in Forrest City, as well as former major league baseball player Don Kessinger. Van Louis McDaniel of Forrest City was Miss Arkansas in 1948. Gilbert Morris was an award-winning Christian author of young adult fiction with more than 200 books to his name. Larry Chism is a longtime fugitive from justice.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Eastern Arkansas: Arkansas, Crittenden, Cross, Lee, Monroe, Phillips, Prairie, St. Francis, White, and Woodruff Counties. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1890.

Bridgforth, Margaret. “Forrest City.” Arkansas Democrat, December 16, 1951, pp. 8–9.

Chowning, Robert W. History of St. Francis County, Arkansas, 1954: A Narrative Historical Edition Preserving the Record of the Growth and Development of St. Francis County, Arkansas, and Chronicling the Genealogical and Memorial Records of its Prominent Families and Personages. Forrest City, AR: Times-Herald Publishing Company, 1954.

Deaderick, Michael R. “Racial Conflict in Forrest City: The Trial and Triumph of Moderation in an Arkansas Delta Town.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Spring 2010): 1–27.

Deane, Ernie. “The Story of Forrest City: ‘Progress.’” Arkansas Gazette, February 2, 1952, p. 5E.

“Forrest City Swamp Democrat Abounds in this Section.” Arkansas Gazette, August 25, 1897, p. 6.

Jenkins, Cary. “Glory Days.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 8, 2019, pp. 1D, 6D.

Patton, Adell Jr. “Surviving the System: Pioneering Principals in a Segregated School, Lincoln High School, Forrest City, Arkansas.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 42 (April 2011): 3–21.

Mike Polston

CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Avery Hotel

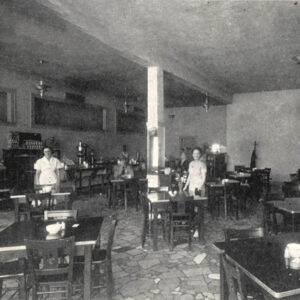

Avery Hotel  Aycock's Cafe

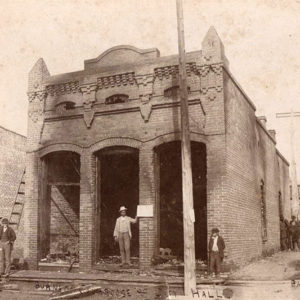

Aycock's Cafe  Box Factory

Box Factory  Chester's Auto Repair

Chester's Auto Repair  Christ Church Parochial and Industrial School

Christ Church Parochial and Industrial School  Chu Building

Chu Building  East Arkansas Community College

East Arkansas Community College  East Arkansas Community College

East Arkansas Community College  Federal Correctional Institution

Federal Correctional Institution  Forrest City Fire Damage

Forrest City Fire Damage  Forrest City Refugee Camp

Forrest City Refugee Camp  Forrest City Refugees

Forrest City Refugees  Forrest City Street Scene

Forrest City Street Scene  Forrest City Street Scene

Forrest City Street Scene  Forrest City Times

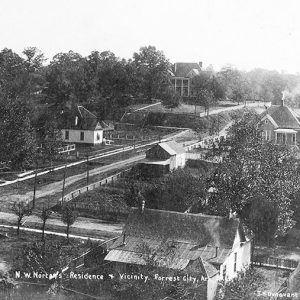

Forrest City Times  Forrest City View

Forrest City View  Al Green

Al Green  Hotel Marion

Hotel Marion  Jackson Street

Jackson Street  Don Kessinger Card

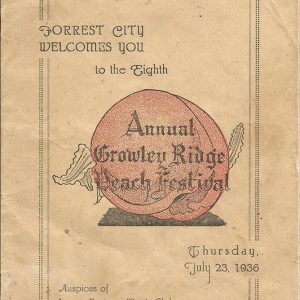

Don Kessinger Card  Peach Festival Program

Peach Festival Program  St. Francis County Museum

St. Francis County Museum  St. Francis County Courthouse

St. Francis County Courthouse  St. Francis County Map

St. Francis County Map  St. Francis River Bridge

St. Francis River Bridge  Steam Plant

Steam Plant  Texas Court

Texas Court

I am looking for any and all information on the Summerfield Baptist Church burning in 1966.

I am the grandson of C. W. Stewart, black superintendent of the black schools. Stewart Elementary was named after him as well. He was also principal of Lincoln High around the late 1930s until around 1946. C. T. Cobb was probably the principal to follow him.