calsfoundation@cals.org

Benjamin Travis Laney Jr. (1896–1977)

Thirty-third Governor (1945–1949)

Benjamin Travis Laney Jr. served two terms as governor of Arkansas. His most notable achievement was the state’s 1945 Revenue Stabilization Law, which prohibited deficit spending. Though he once said, “I am not a politician,” his conservative views put him in the spotlight at a time when the Democratic Party was becoming more liberal. Although he opposed desegregation, the University of Arkansas School of Law became the South’s first all-white public institution to admit black students during his tenure.

Ben Laney was born on November 25, 1896, in Jones Chapel (Ouachita County), the son of Benjamin Travis Laney and Martha Ellen Saxon. He was one of eleven children, and his father was a farmer. He entered Hendrix College in Conway (Faulkner County) in 1915 but left in 1916 to teach before serving in the U.S. Navy during World War I. He received a BA from Arkansas State Normal School (now the University of Central Arkansas) in 1924.

Laney worked in business and banking from 1925 to 1926 in Conway, where he and Lucile Kirtley were married on January 19, 1926; they had three sons. In 1927, Laney returned to Ouachita County, where his business dealings included oil, banking, farming, cotton gins, and retail stores.

He was the mayor of Camden (Ouachita County) from 1935 to 1939 and a member of the Arkansas Penitentiary Board from 1941 to 1944. His activities on behalf of John L. McClellan’s 1942 U.S. Senate bid solidified a friendship and political alliance.

A relative unknown when he ran for the 1944 Democratic gubernatorial nomination, he had the support of conservative business and financial interests. His opponents were former congressman David D. Terry and State Comptroller J. Bryan Sims. Sims withdrew ten days before the election amid accusations of a negotiated deal, and Laney easily defeated Republican opponent H. C. Stump in the general election, as was the norm in this essentially one-party political era. His re-nomination and reelection in 1946 were effortless.

The governor’s work on behalf of efficiency, economy, and consolidation in state government and his encouragement of industrialization and broadly based economic development earned him the nickname “Business Ben.” These activities and his opposition to organized labor strengthened his ties with Arkansas business conservatives.

Laney’s most notable achievement was the 1945 Revenue Stabilization Law, which combined flexibility in funding state programs with a priority mechanism to prevent deficit spending. Before 1945, appropriations were tied to specific taxes; as a result, some revenue streams came up short while others had more money than needed. The new law created a single general fund from which all state appropriations were made and prohibited departments and institutions from spending if cash was not available. It also created an orderly system of budget cuts if the revenue was not available.

In 1947, he successfully urged the legislature to create a legislative council to provide research and bill-drafting assistance for Arkansas’s part-time legislators. However, Laney is remembered less for his streamlining of governmental structure and finance than for his opposition to proposals that would alter race relations and weaken or end segregation. He spoke out against progressive federal initiatives to outlaw lynching and the poll tax and quietly worked to prevent desegregation of state professional and higher education programs. Laney claimed that his actions were based on constitutional principles and states’ rights philosophy and not on racial considerations, but he had praised Arkansas and Arkansans as being close to what he described as good and pure Anglo-Saxon stock. Although Laney was Arkansas’s last philosophically consistent segregationist governor, it was on his watch that the UA School of Law admitted its first black student in 1948.

In 1948, Laney broke with the administration of Harry S Truman (which he had enthusiastically welcomed in 1945) over President Truman’s use of federal law to require fair employment practices and end racial discrimination. The governor was a leader in the States’ Rights Democrats (Dixiecrats) movement, and the Dixiecrats considered him for a presidential or vice presidential nomination.

As governor, Laney had campaigned for the Dixiecrat ticket (Strom Thurmond and Fielding Wright), despite his doubts about the success of a third party in the South, but Sidney S. McMath, elected governor in 1948, vigorously supported Truman and helped hold Arkansas in the Democratic column in the presidential election. With the Democratic Party divided due to Truman’s civil rights policies, many Southerners wanted to see Strom Thurmond’s name on the ballot instead of Truman’s. However, McMath’s campaigning at the Democratic State Convention prevented Thurmond from getting the nomination. Laney was so bitter toward McMath that, in 1950, he challenged McMath and sought a third term (a feat accomplished only once before in Arkansas). McMath, with the support of the black electorate and organized labor, handily defeated the former governor in the general election.

Laney remained a spokesman for states’ rights but disapproved of Governor Orval E. Faubus’s actions during the 1957 Little Rock Central High School desegregation crisis. Laney believed that Faubus was less a defender of Southern traditions on race and states’ rights than a demagogue interested in immediate political gain.

Laney embraced the economics of a post–World War II “New South” and toiled to attract industry and investment capital to Arkansas. An articulate spokesman for the state, he traveled the country, promoting a new image for Arkansas. However, regarding race, Laney clung to an old Southern style of benign paternalism. The linking of economic growth with a more enlightened view of racial integration was left to Laney’s successors.

In 1969, Laney served as a delegate to the Arkansas Constitutional Convention. He was active in the reelection campaigns of McClellan (1972) and Senator J. William Fulbright (1974), two close friends whom he supported in spite of their Democratic affiliation. Laney, though, supported the presidential candidates George Wallace (American Independent Party) in 1968 and Gerald Ford (Republican Party) in 1976 because of his hostility toward the new brand of Democrats. He managed the rice farm of Winthrop Rockefeller in the 1960s and spent his last years in Magnolia (Columbia County) looking after his own business affairs.

Laney died on January 21, 1977, in Magnolia and was buried in Camden Memorial Cemetery.

For additional information:

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography, 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Governor Benjamin Travis Laney Jr. Papers. University of Central Arkansas Archives and Special Collections, Conway, Arkansas.

Laney, M. Melissa. “Forgotten but Not Forgiven: The Legacy of Governor Ben T. Laney.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2009.

Tom Forgey

Magnolia, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Politics and Government

Politics and Government World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

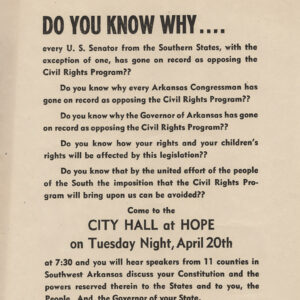

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Laney Broadside

Laney Broadside  Ben Laney

Ben Laney  Ben Laney with Congressional Delegation

Ben Laney with Congressional Delegation  Benjamin Laney

Benjamin Laney  Ben Laney

Ben Laney

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.