calsfoundation@cals.org

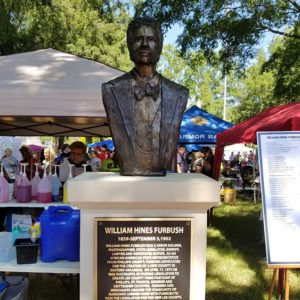

William Hines Furbush (1839–1902)

William Hines Furbush was an African American member of the Arkansas General Assembly and the first sheriff of Lee County. His political career began in the Republican Party at the close of Reconstruction and ended in the Democratic Party just as the political disfranchisement of African Americans in the post-Reconstruction era began.

William Furbush was born in Carroll County, Kentucky, in 1839 and was often described as a “mulatto.” Nothing is known of his parentage or childhood, but judging from his literacy and scripted handwriting, he received an early and formal education. Around 1860, Furbush is known to have operated a photography studio in Delaware, Ohio. In March 1862, he traveled to Union-controlled Helena (Phillips County) on the Kate Adams, where he continued to work as a photographer.

In December of that year, he married Susan Dickey in Franklin County, Ohio. In February 1865, he joined the Forty-second Colored Infantry at Columbus, Ohio. At the rank of Commissary Sergeant, he was honorably discharged in January 1866, and later that year, he departed for Liberia on the Golconda, an American Colonization Society (ACS) ship. In the ACS roll books, “Willis H. Furbush” was described as a twenty-seven-year-old photographer of the Presbyterian faith, with a “good” education and traveling with no family. The ACS, a benevolent organization operating under racist pretensions of white progress and black inferiority, offered transportation, land, independence, and freedom for African Americans willing to immigrate to Liberia. Its appeal waned during Reconstruction, as African Americans acquired freedom and political rights, and Furbush left Liberia after eighteen months.

By 1870, Furbush was back in Arkansas, living in Phillips County with his wife and two young sons and working as a photographer. He had property and real estate worth $2,500. In 1872, he was elected a Republican representative to the General Assembly for the eleventh district (Phillips and Monroe counties). While in the legislature, Furbush became involved in civil rights issues. In February 1873, he assaulted two waiters after they refused him service in a Little Rock (Pulaski County) restaurant and was fined $75. Two months later, following the passage of Arkansas’s 1873 Civil Rights Act, he and three other African Americans (R. A. Dawson, J. R. Roland, and Lloyd G. Wheeler) were refused service at Wilds Opera House Saloon on Main Street. The trio filed a lawsuit, and on appeal, African American lawyers Lloyd Wheeler and Mifflin Gibbs won the case against the barkeeper. The verdict of $46.80 marked the only known victory under Arkansas’s 1873 Civil Rights Act.

Furbush’s main accomplishment was the establishment of Lee County, with Marianna as the county seat. Phillips County opposed the bill, which would have named the proposed county “Coolidge County” and then, in a second version, “Woodford County.” Both versions were defeated. The persistent Furbush finally pushed it through when the county’s name was changed to honor the South’s “Great Chieftain,” Robert E. Lee, and he was named sheriff of the new Lee County.

Within a year, Furbush remarried, after his first marriage to Susan had apparently ended. He married eighteen-year-old schoolteacher Emma S. Owens on April 7, 1874, in Memphis, Tennessee.

Furbush served as sheriff from 1873 to 1879, winning reelection twice by cooperating in a fusion political system that combined black Republican voting power with the economic power of white Democrats. Ideally, fusion avoided political violence by dividing uncontested political offices between the parties. Fusion in Lee County was barely off the ground when Republicans, in October 1874, upset by Furbush’s campaign tactics, confronted him in the streets of Marianna. Furbush tussled with at least one black Republican before he was attacked from behind with a knife. Confused and with cuts about his neck and face, Furbush shot and mortally wounded twenty-seven-year-old Tom Wood, the son of George Wood and brother of future Democratic Lee County politician James E. Wood. Furbush survived and formed a posse to reestablish order and capture the “conspirators.” However, tensions between whites and African Americans escalated, and an African American mob formed reportedly to burn Marianna. The mob disbanded when James Wood and others confronted and stood the mob down.

Furbush continued to move closer to the Democratic Party. In 1876, he was dismissed as sheriff by a circuit judge for failure to respond to a writ of habeas corpus and to control a county prisoner. Against some Democrats’ wishes, Democratic governor Augustus H. Garland reinstated him. In the late summer of 1878, he was named the Democratic nominee for state representative for Lee County and gave up his position as sheriff to a “white candidate.” His decision was praised in both the Marianna Index and Arkansas Gazette. The 1878 election season, notorious in Lee and Phillips counties for the intimidation of Republicans and African Americans by Democratic militias, sent Furbush to the General Assembly as a Democrat—perhaps the first African-American Democrat.

The legislature in 1879 was rocked by charges of bribery in the House’s election of a new U.S. senator. Furbush, a vocal proponent for the formation of an investigation committee, suddenly found his own character and honesty questioned. Furbush struck back and vigorously defended himself, often clashing with committee chairman, William Meade Fishback. The investigation concluded with a final report but no criminal charges.

In March 1879, vindicated of bribery charges, Furbush left for booming Colorado, publicly saying that he might return in a month. However, it seems he fell out of favor with Lee County’s officials, and reports were leaked that he left the state behind on his debts. Following his departure, his wife, Emma, died from yellow fever in her native city of Memphis. Their newborn daughter, Eve, died of dysentery a few days later. In Colorado, Furbush worked as an assayer in the mining town of Bonanza and was reportedly a gambler and barber in Denver. In Bonanza, Furbush narrowly escaped a lynch mob after he killed the town’s constable. He was acquitted at his trial, but the event may have scarred him. In February 1884, the Arkansas Gazette reported Furbush had attempted suicide by morphine.

Nearly three years later, in November 1886, Furbush was biding his time in Washington Court House, Ohio, teaching music. Two years later, in 1888, Furbush had returned to Little Rock and reestablished himself as a lawyer and Democratic Party activist. In December 1889, he and E. A. Fulton announced the publication of the National Democrat, a Democratic paper for “colored citizens of Arkansas.” His purpose, to attract black voters to the Democratic Party, was largely unsuccessful. However, he was still a powerful foe of the “lily-white” Republicans, a new racist element in the Republican Party.

Furbush likely became frustrated in the early 1890s with the passage, by Democrats, of new election and separate coach laws, which effectively disfranchised black men and made all African Americans second-class citizens. He left Little Rock for South Carolina around this time and later relocated to Savannah, Georgia, in 1900. He made a final move to the National Home for Disabled Veterans in Marion, Indiana, in October 1901. He died there on September 3, 1902, and was interred at the Marion National Cemetery.

Furbush’s role in Arkansas politics and African-American history is not well known. Lee County has no public tribute to Furbush, and local history is mixed on his political role there. A positive memory, however, survived within the black community, at least into the 1930s. A Works Progress Administration (WPA) interviewee recalled, “Every slave could vote after freedom. Some colored folks held office. I knew several magistrates and sheriffs. There was one at Helena and one at Marianna. He was a High Sheriff.”

For additional information:

Apple, Nancy and Suzy Keasler, eds. History of Lee County, Arkansas. Dallas: Curtis Media Group, 1987.

Foner, Eric. Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

“Negro Intimidation. Attorney Furbusch Tells What He Knows of the Practices in Pulaski County.” Arkansas Gazette. August 2, 1889, p. 8.

Wilson, Douglas. “William Hines Furbush: African-American Photographer, Soldier and Politician.” Military Images 26 (July/August 2004): 18–23.

Wintory, Blake. “William Hines Furbush: An African American, Carpetbagger, Republican, Fusionist and Democrat.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 63 (Summer 2004): 107–165.

Blake Wintory

Little Rock, Arkansas

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Politics and Government

Politics and Government Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Furbush Bust

Furbush Bust  William Furbush

William Furbush

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.