calsfoundation@cals.org

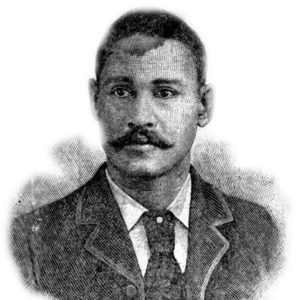

John Gray Lucas (1864–1944)

John Gray Lucas’s life was representative of the broad changes that occurred in the patterns of race relations in Arkansas and the South during the latter half of the nineteenth century. From the end of the Civil War until the early 1890s, African Americans could obtain an education and then enter politics as independent, forthright champions of their race’s interests. After that point, as historian J. Morgan Kousser observed, “most blacks would have to emigrate to the North, choose other professions, or settle for the role of white-appointed race leader, with all constraints that role imposed on their statements and actions.” Lucas served in the Arkansas General Assembly and advocated for the rights of African Americans during his tenure in office.

John Lucas was born on March 11, 1864, in Marshall, Texas. Official records list his father’s name as unknown and his mother’s name as “Bettie.” Lucas moved to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), where he attended public schools. He entered the Branch Normal College of Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff), but a few months before graduation, he entered the merchandising business, and it was two additional years before he earned his degree.

In October 1884, he entered the Boston University School of Law and was graduated in 1887, the only African American in a class of fifty-two students and one of seven students graduating with honors.

In December 1886, he was interviewed by the Boston Daily Globe and asked about racial conditions in Pine Bluff. Lucas responded that three of Pine Bluff’s eight city councilmen were African Americans and that African Americans held the offices of county coroner and county circuit clerk. African Americans made up half of the members of the local police force and half of the local justices of the peace and often served on juries. In addition, a black entrepreneur owned the city’s principal streetcar system. He also noted that, on public transportation throughout Arkansas, “there was neither distinction or separation [by race].” Contrasting the lot of black citizens in Massachusetts with conditions in Arkansas, he wondered why “more colored young men from the North did not make Arkansas their home. It is an inviting field for them and a grand opportunity to make something of themselves.”

Lucas followed his own advice. He returned to Arkansas and was admitted to the state bar. Soon afterward, he was named assistant prosecuting attorney for Pine Bluff and Jefferson County. His abilities brought him to the attention of Judge H. C. Caldwell, who appointed him commissioner for the U.S. Circuit Court, Eastern District of Arkansas. He was also elected to the Republican state and county central committees and served on the Republican Eleventh Judicial District Central Committee.

In the fall of 1890, he was elected as a state representative from Jefferson County. Entering the Arkansas General Assembly at the very time that a new wave of racism was inundating the American South, he emerged as a leader among the legislature’s twelve black lawmakers. He is especially remembered for the eloquent address he delivered in February 1891 against a Jim Crow separate-coach bill that would mandate racial segregation on Arkansas’s railroads. Although the measure was passed easily by the legislature’s white Democratic majority, Lucas’s address against it won praise from his white adversaries. The Arkansas Gazette and the Arkansas Democrat, the state’s most important Democratic newspapers, characterized Lucas as “a fluent debater,” “unquestionably the ablest and most brilliant representative of his race in the state, and it might truthfully be (for his age) in the South,” “a born leader of his people” for whom in 1891 there was “certainly a bright future in store.”

The same legislature adopted a series of measures that effectively disfranchised a majority of black voters and removed virtually all African Americans from public office in the state during the next four years.

By 1893, Lucas had left Arkansas and relocated to Chicago, Illinois, where he established a lucrative law practice, conducted from his spacious suite of offices at 88 Dearborn Avenue in the downtown Chicago Loop. He gained a reputation as an expert in criminal law and appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court on four occasions. By the early twentieth century, the local African-American press was referring to him as “a black millionaire.” He became active in Republican politics and obtained appointments as assistant corporation counsel and first assistant recorder of deeds in Cook County.

Lucas, along with many other African Americans, left the Republican Party during the Great Depression and became a Democrat. In 1934, he was appointed assistant U.S. attorney in Cook County, a position he held until the year of his death. He died on October 27, 1944, in Chicago and is buried there in Lincoln Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, Olive Gulliver Lucas, and his daughter; a son had predeceased him.

For additional information:

Graves, John William. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

John William Graves

Henderson State University

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

African American Legislators (Nineteenth Century)

African American Legislators (Nineteenth Century) Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change John Gray Lucas

John Gray Lucas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.