calsfoundation@cals.org

Sharecropping and Tenant Farming

Farm tenancy is a form of lease arrangement whereby a tenant rents, for cash or a share of crops, farm property from a landowner. Different variations of tenant arrangements exist, including sharecropping, in which, typically, a landowner provides all of the capital and a tenant all of the labor for a fifty percent share of crops.

Tenancies have been used widely throughout Arkansas, but prior to the Civil War, slaves worked most vast agricultural tracts along the Mississippi River planted in cotton. When the South lost the war, bringing slavery to an end, Arkansas landowners and freed slaves then began negotiating new labor relationships to cultivate land up and down the Arkansas Delta. While some planters preferred day labor, using workers hired by the hour, week, or month, other landowners opted for tenant farmers. In some instances, a hybrid of the two existed. For example, after a farmer got his crop harvested, his family members might work as day laborers for other tenants to supplement their income or provide “Christmas money.” Hired labor directly supervised by the landowner or his manager provided the greatest level of labor control, but it required periodic cash outlays on payday, and the planter took all of the crop risk. Tenants allowed the landowner to conserve cash for other crop expenses, and the tenant shared crop risk on leased land. In some instances, such as on the Twist Plantation during the 1930s, some land was leased and other acreage farmed by hired help.

Tenancy arrangements in Arkansas prior to mechanization typically were forty-acre operations. Family members provided all of the labor to plant, cultivate, and harvest the crops. For use of the land, they paid a percentage of crops harvested (called crop rent) or a cash payment (called cash rent). Oral or written contracts spelled out responsibilities under the contract.

Cash rent contracts required tenants to pay landowners a fixed amount per acre each year. If a farmer paid a landlord twenty-five dollars per acre to rent ground in January of the farm year, it was “front end” cash rent. “Back end” cash rent allowed a farmer to pay in December each year from crop sale proceeds. The amount of cash rents depended on such factors as quality of the soil, drainage, and the crops to be grown. As might be expected, tenants preferred “back end” rent to save interest on borrowed money and conserve cash for crop expenses such as seed, fertilizer and labor.

The most common lease arrangement in Arkansas called for crop rent, requiring a tenant to pay usually twenty-five percent to fifty percent of crops harvested. These percentages could vary from year to year, farm to farm, and from crop to crop. To guarantee crop loan repayment, lenders and sometimes suppliers took a first lien on the tenant’s share of crops and equipment used to produce them. Such liens meant that holders had a legal right to crop proceeds until loans were paid in full. Should proceeds not be sufficient to pay off the lender, a foreclosure could occur with collateral (the equipment and any other asset used to secure the loan) seized and sold to pay off the debt.

Crop rent came from crops at harvest, and cotton or grain hauled to gins and elevators was split according to contract percentages. Tenants and landowners each received their respective shares of the crop. If a lien existed on the tenant share, checks for crop sale proceeds usually had both the lien holder’s and the farmer’s name so neither could cash the check without both endorsements. By this means, lenders helped enforce their legal rights and protected themselves from conversion of crop proceeds.

Tenants provided equipment and capital to farm, if they had them. When they lacked such assets, sharecropping (a form of tenancy usually accepted by only the poorest farmers) allowed them to make a crop. Since equipment and “furnish” (production supplies and personal needs) came from the landowner, sharecroppers received a smaller portion of crops, typically fifty percent. Significantly, under sharecropping contract terms, title to the entire crop, not just the landowner’s contract share, could be held by the owner. Those who held title to crops could sell all of the commodities without consulting the sharecropper. Sometimes crops were sold to family-owned gins or grain elevators at prices established by landowners without shopping or negotiating, a process that tended to favor the landowner.

Many large planting companies required sharecroppers to purchase business and personal supplies from commissary stores as a condition to farm the land. Farmers received “doodlum” books (vouchers) for credit at the company store. Prices there sometimes were well in excess of those charged at town stores. The March 1935 edition of Today magazine reported markups in the twenty-five percent range at Southern plantation commissaries. For example, company stores priced potatoes at $2.25 when they were $1.75 in town.

Abusive business practices such as these generated ongoing tensions between Arkansas tenants and landowners, since many tenants never got out of debt. Some farmers sought to organize better treatment, forming such groups as the Agricultural Wheel for this purpose. An organizational meeting of one union was at the center of violence that erupted in Elaine (Phillips County) in 1919. Tenant difficulties increased in the early 1930s when the Great Depression decimated agriculture along with the rest of the economy. Arkansas farmers faced “nickel cotton” (a market price of five cents per lint pound, which was at the low-end of its historic market range) and the locked doors of banks that became insolvent. Unable to borrow money to make crops, many tenant farmers joined the exodus made famous by John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. The administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt created federal programs to help prop up cotton prices, including a plan to compensate farmers who agreed to forego planting acreage in exchange for parity payments from the federal government. Though the program stipulated that landowners share parity payments with tenants, some owners kept all of the money, and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) compliance efforts proved ineffectual. Additionally, owners evicted tenants since acreage reduction made them unnecessary, another violation of regulations.

Such abuses caused tenants around Tyronza (Poinsett County) to form the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union in 1934. The union’s stated mission to better the conditions of farm tenants and workers kept it in ongoing conflict with the region’s powerful planters and political allies throughout the 1930s. Though the organization achieved some successes, they tended to be on an individual level and not systemic. For example, the union failed to achieve changes in government farm assistance sufficient to stop widespread abuse. This USDA financial assistance, developed initially as a temporary fix for Depression-era problems, became ingrained in agricultural economics and grew into a major source of income for state farmers.

The growth of state tenant farming reflected a national trend. In the late 1800s, twenty-five percent of American farmers operated as tenants. By the late 1930s, forty percent farmed as tenants. Today, almost all Arkansas farmers rent some of the land they cultivate.

Modern tenant farmers tend to be corporate entities to take advantage of legal liability protection and other business and tax advantages. They have become larger operations to achieve economies of scale and marketing clout, and such Arkansas farm operations are among the nation’s most productive. The USDA recorded that, in 2004, Arkansas farmers harvested their largest cotton and rice crops ever. The state’s production of cotton in 2004 set a record with 2.1 million bales. Rice harvested reached a record high107.4 million hundredweight. Soybeans, the state’s most frequently planted crop, amounted to 124.4 million bushes in 2004, the second largest soybean crop in Arkansas history. Thus does tenant farming survive, in modified form, in Arkansas.

For additional information:

Auerbach, Jerold S. “Southern Tenant Farmers: Socialist Critics of the New Deal.” Labor History 7 (Winter 1966): 3–74.

Grubbs, Donald H. Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1971.

Manley, Patricia. “The Pursuit of Land: Southern Tenancy, Manly Independence and Mobility on the Agricultural Ladder.” MA thesis, California State University San Marcos, 2014. Online at https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/z603qx80x?locale=en (accessed July 7, 2022).

McNeilly, Donald P. The Old South Frontier: Cotton Plantations and the Formation of Arkansas Society, 1819–1861. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Payne, Elizabeth Ann. “The Lady Was a Sharecropper: Myrtle Lawrence and the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.” Southern Cultures 4.2 (1998): 5–27.

Southern Tenant Farmers Museum Collection. Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, Arkansas.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1996.

Van Hawkins

Arkansas State University

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Flood of 1927

Flood of 1927 Labor Movement

Labor Movement Military Farm Colonies (Arkansas Delta)

Military Farm Colonies (Arkansas Delta) Poverty

Poverty Arkansas City Cotton Picker

Arkansas City Cotton Picker  England Cotton Fields

England Cotton Fields  Rickets Victim

Rickets Victim  Scott Plantation Settlement Building

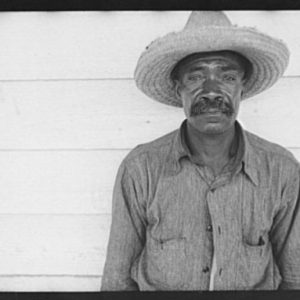

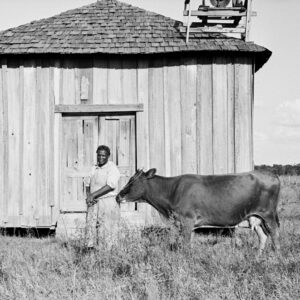

Scott Plantation Settlement Building  Sharecropper

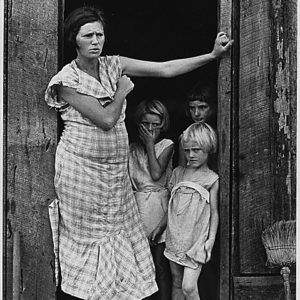

Sharecropper  Sharecropper Family

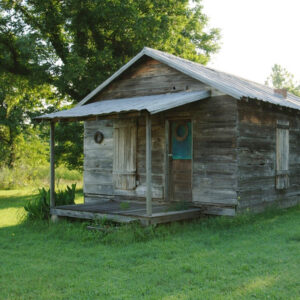

Sharecropper Family  Sharecropper House

Sharecropper House  Sharecropper House

Sharecropper House  Shotgun Tenant House

Shotgun Tenant House  Tenant House

Tenant House

There should be more written about the sharecroppers and the people who worked the fields of Scott, Arkansas, on the R. H. Alexander plantation. There were a number of families who lived and worked the fields chopping and picking cotton by hand for this plantation owner: the Randolph family, Alexander family, Johnson family, Riley family, Lewis family, and many more.