calsfoundation@cals.org

Jimmy Driftwood (1907–1998)

aka: James Corbett Morris

Jimmy Driftwood was a prolific folk singer/songwriter who wrote over 6,000 songs. He gained national fame in 1959 when Johnny Horton recorded Driftwood’s song, “The Battle of New Orleans.” Even after Driftwood had risen to fame, he continued living in rural Stone County, spending most of his time promoting and preserving the music and heritage of the Ozark Mountains.

Jimmy Driftwood was born James Corbett Morris in West Richwoods (Stone County) near Mountain View (Stone County) on June 20, 1907, to Neal and Allie Risner-Morris. He was given the name Driftwood as the result of a joke his grandfather had played on his grandmother. When the two went to visit their new grandson, Driftwood’s grandfather arrived first and wrapped a bundle of old sticks in a blanket. When Driftwood’s grandmother arrived, she was handed the bundle and remarked, “Why, it ain’t nothing but driftwood.”

Music played a large role in Driftwood’s life from his earliest years. His father, a farmer by trade, was also an accomplished folk singer, and it was through him and other local musicians that Driftwood was first exposed to the songs of the Ozarks. While still a small child, Driftwood learned to play the guitar his grandfather had made from a piece of a rail fence and other salvaged materials. He would continue to play this unusual-looking instrument throughout his career; it became his trademark and is currently on display in the Arkansas Entertainers Hall of Fame in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County).

Driftwood was a good student during his eight short school terms in the one-room school at Richwoods (Stone County). Although he had not attended high school, he passed the Arkansas Teachers Exam when he was sixteen. He spent the next few years teaching in one-room schoolhouses in Prim (Cleburne County), Roasting Ear Creek (Stone County), Timbo (Stone County), and Fifty-six (Stone County), while attending high school in Mountain View. After graduating in 1928, he attended Arkansas State Teachers College (now the University of Central Arkansas) in Conway (Faulkner County), before eventually attending John Brown College (now John Brown University) in Siloam Springs (Benton County). In addition to teaching, Driftwood played the fiddle at local dances and other venues to earn money for college.

Driftwood left college before receiving a degree and rambled for a while, eventually ending up in Arizona. While in Phoenix, he won a local talent show, which led to weekly performances on a local radio station. He left Phoenix in 1935 and returned to Stone County to teach in Timbo. Although he had been writing songs and poetry for years, it was at Timbo that Driftwood began teaching his students history through song. It was also there that he fell in love with a former student, Cleda Johnson. They were married on November 26, 1936. The couple had three sons.

After his marriage to Cleda, Driftwood continued to teach at area schools as well as write songs and play folk music. In 1947, the couple was able to purchase the 150-acre farm where they would live the rest of their lives. After years of taking summer and night classes, Driftwood finally received his BSE degree from Arkansas State Teachers College on May 29, 1949, and, with it, became principal of the school in Snowball (Searcy County).

In the early 1950s, Driftwood began testing the waters of commercial music. He submitted songs he had written to several record companies, including Blasco Music Company and Shelter Music, both in Kansas City, Missouri. Both Shelter and Blasco recorded some of Driftwood’s material, but with little commercial success. In 1957, Driftwood went to Nashville, Tennessee, and auditioned for RCA record executive Don Warden, who signed him to a contract. Driftwood, under the guidance of RCA’s Chet Atkins, recorded his first album, titled Jimmy Driftwood Sings Newly Discovered American Folk Songs, in less than three hours. It was released in 1958 and saw limited success. The album featured “The Battle of New Orleans,” a song Driftwood had composed in 1936 to help his students differentiate between the War of 1812 and the Revolutionary War. The song was a hit among those who heard it, but the strict broadcast standards of the day virtually excluded it from the airways because of the words “hell” and “damn” in the lyrics. After the release of Driftwood’s album, he quit his job as principal of Snowball School and began making regular appearances at such popular country music venues as the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tennessee; the Ozark Jubilee in Springfield, Missouri; and the Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport, Louisiana, where he met Johnny Horton, who expressed an interest in recording “The Battle of New Orleans.” Driftwood revamped the song’s lyrics to make them acceptable for radio.

Horton’s recording of “The Battle of New Orleans” stayed on top of the country singles chart for ten weeks in 1959 and also held the top spot on the pop charts for six weeks. Partially because of the popularity of this song, Driftwood was asked to perform his traditional American music for Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev during his visit to the United Nations in 1959. Driftwood and Horton took Song of the Year honors at the second Grammy awards ceremony in 1959. Driftwood’s “Wilderness Road” also received a Grammy nomination for Best Folk Performance of the Year in 1959, and the same year, Eddie Arnold received a Grammy nomination in both country and folk categories for his version of Driftwood’s most-recorded song, “Tennessee Stud.”

Driftwood received another Grammy nomination for the 1961 song, “Billy Yank and Johnny Reb.” During the next few years, Driftwood, often joined on stage by Cleda, performed at Carnegie Hall, the Grand Ole Opry, and major folk festivals. On March 31, 1962, Driftwood was elevated from a regular guest to starring member of the Grand Ole Opry. He also returned to the educational profession in 1962, teaching folklore at the University of Southern California in Idyllwild. Driftwood also released his final album on the RCA label, Driftwood at Sea. However, the album sold poorly, and Driftwood longed to return to Stone County.

In 1963, Driftwood returned to Timbo. He helped to form the Rackensack Folklore Society, was one of the visionaries in creating the Arkansas Folk Festival in Mountain View, and was a leading force in the establishment of the Ozark Folk Center. Having more national notoriety than anyone else involved in Arkansas’s folk scene, Driftwood was largely responsible for promoting and securing funding for folk celebrations and the folk center. He astounded city officials by obtaining $2.1 million toward the construction of the center from the Ways and Means Committee of the House of Representatives.

Driftwood also became involved in environmental issues. He helped secure the designation of the Buffalo River as the first national river and helped persuade the United States Forest Service to develop and promote the Blanchard Springs Caverns. He held several prominent positions, including chairman of the Arkansas Parks and Tourism Commission, member of the Advisory Committee of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and the National Advisory Board for the National Endowment for the Arts, and musicologist for the National Geographic Society, producing Music of the Ozarks, the society’s first album of American folk music

In 1975, Driftwood was relieved of his position as musical director of the Ozark Folk Center. This controversial removal caused a backlash among Driftwood’s friends and musical companions in the Rackensack Folklore Society. The majority of Rackensackers, who had been the heart of the folk center’s programs, cut ties with the folk center and left in search of a new performance venue. Driftwood purchased a three-acre plot of land north of the folk center, and by 1976, he and the Rackensackers had built a simple wood-frame building for the performance of traditional Arkansas folk music.

Driftwood died on July 12, 1998, in Fayetteville (Washington County), where he had been hospitalized. His ashes were scattered on his farm near Timbo.

For additional information:

Kellams, Kyle. “The Legacy of Jimmy Driftwood.” KUAF: Ozarks at Large, July 27, 2020. https://www.kuaf.com/ozarks-at-large-stories/2020-07-27/the-legacy-of-jimmy-driftwood (accessed July 28, 2023).

Lucas, Ann Davenport. “The Music of Jimmy Driftwood.” Mid-America Folklore 15 (Spring 1987): 27–41.

Jimmy Driftwood Collection (M98-02). University of Central Arkansas Archives. University of Central Arkansas, Conway, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://uca.edu/archives/m98-02-jimmy-driftwood-collection/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Streeter, Richard Kent. The Jimmy Driftwood Primer. Calhoun, GA: The Jimmy Driftwood Legacy Project, 2003.

Zac Cothren

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

"The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood

"The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood  Jimmy Driftwood at Home

Jimmy Driftwood at Home  Jimmy Driftwood

Jimmy Driftwood  Jimmy Driftwood

Jimmy Driftwood  Jimmy Driftwood

Jimmy Driftwood  Jimmy Driftwood and Friends

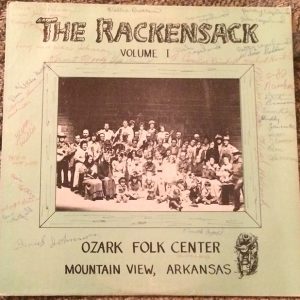

Jimmy Driftwood and Friends  Rackensack Album

Rackensack Album

In the late 1970s, I was on some kind of school trip with several younger boys and three adults. We were in Little Rock, Arkansas, and got rained out of our camp. We ended up staying at these folks’ house and they had records everywhere in racks. The records were brand-new in their wrappers, and they said Jimmy Driftwood on them. I had been singing “Battle of New Orleans” for a long time before I ever took this trip. We stayed with this family, and I believe it was Jimmy’s. For one night, the nine young boys and three adults slept on the floor of these folks’ home. Thank you to Mr. and Mrs. Driftwood for opening their hearts and their home to us boys. We then got back to our camp, put our camp back together, and finished our outing.