calsfoundation@cals.org

Marquette-Joliet Expedition

In 1673, Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, and Louis Joliet (or Jolliet), a fur trader, undertook an expedition to explore the unsettled territory in North America from the Great Lakes region to the Gulf of Mexico for the colonial power of France. Leaving with several men in two bark canoes, Marquette and Joliet entered the Mississippi River and arrived in present-day Arkansas in June 1673. They were considered the first Europeans to come into contact with the Indians of east Arkansas since Hernando de Soto’s expedition in the 1540s. The goal given Marquette, Joliet, and their men was to document, for French and Canadian officials, an area that had been largely unknown until the late seventeenth century.

Both explorers were from very different backgrounds. Father Jacques Marquette was born in Laon, France, in 1637 to a family steeped in military and civic service. He entered the Society of Jesus and studied at various Jesuit colleges in France before arriving in Canada in 1666. In Canada, Marquette became fluent in many American Indian languages and was given the task of introducing Christianity to the tribes of the Great Lakes region. By the 1670s, he was drawn into a proposition by the French governor, Louis de Baude Frontenac, to go on a voyage of discovery along the Mississippi River.

Marquette’s traveling companion, Louis Joliet, was born in Canada in 1645. By trade, he was a wagon maker and explorer who excelled in mathematics and attended Jesuit schools. However, Joliet abandoned his clerical studies to go on an exploration of the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi River with Father Marquette and other Frenchmen as early as 1672. He hoped to make a fortune in the fur trading industry on this expedition.

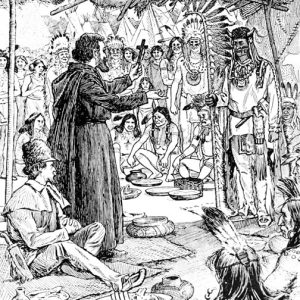

Along the voyage south, Marquette and Joliet talked with local American Indian tribes and made maps of the region. Arriving in Arkansas, they stopped at Kappa, a Quapaw village about twenty miles from the mouth of the Arkansas River. The Quapaw greeted the travelers with reluctance but finally warmed up to them, the first Europeans seen in the area in over 100 years. As a gesture of friendship upon greeting the travelers, the Quapaw offered Marquette a ceremonial pipe, the calumet, which he smoked with tribal leaders. Marquette remarked the Quapaw men were “strong, well made” and beaux homes (handsome men). After three days and nights of feasting, both Marquette and Joliet were able to comment that the Quapaw were likeable and could become possible French allies in the settlement of the lower Mississippi River Valley.

Marquette and Joliet’s journey was curtailed when the Quapaw warned the explorers that Spanish colonials were located further south. Not wishing to lose the observations they had noted about the region to the Spanish if they came into contact with them, Marquette and Joliet returned to the Great Lakes region at the head of Green Bay, secure in the knowledge that the Mississippi River did indeed empty into the Gulf of Mexico. This was based on reports from Arkansas’s Quapaw Indians. However, before they left, Marquette and his Frenchmen erected a cross in the village of Kappa.

The importance of the expedition of Marquette and Joliet includes the realization of French dreams of an all-water route between the Great Lakes region and the Gulf of Mexico. French officials—based on reports from Marquette, Joliet, and Arkansas’s Quapaw Indians— could begin to build forts to along the river, place a barrier between themselves and the English colonies, and expand the Catholic faith. More importantly, the information gained by the explorers paved the way for the expeditions of other Frenchmen, including René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, in 1682 and Henri de Tonti, who came to Arkansas and established Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) in 1686, the first European settlement in the Lower Mississippi River Valley. Marquette and Joliet also established that American Indians in the lower Mississippi River Valley, especially those in Arkansas, could become valuable allies to the French.

After the expedition, Father Marquette returned to work among the Kaskaskia Indians at Starved Rock, near present-day Utica, and died in on May 18, 1675, at the age of thirty-nine after catching a cold. His remains were returned to the Catholic mission at Mackinac in present-day Michigan. His partner in exploration, Louis Joliet, returned to Quebec, where he married. He was given a land grant of the Island of Anticosti in Quebec and continued to explore the area, including Labrador, on the east coast of Canada. In 1680, Joliet was appointed royal hydrographer (responsible for the scientific study of seas, lakes, and streams) and granted the seignory of Joliet (south of Quebec) in 1697. He died in May 1700 in Canada, and his burial place is unknown.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris. Colonial Arkansas, 1686–1804: A Social and Cultural History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

———. Rumble of a Distant Drum: The Quapaw and Old World Newcomers, 1673–1804. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

———. Unequal Laws Unto a Savage Race: European Legal Traditions in Arkansas, 1686–1836. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1985.

Coleman, Roger. The Arkansas Post Story. Sante Fe: Division of History, Southwest Cultural Resources Center, Southwest Region, National Park Service, Deptartment of the Interior, 1987.

“Jacques Marquette, S.J.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09690a.htm (accessed July 28, 2023).

“Louis Joliet.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08496a.htm (accessed July 28, 2023).

Nelson, Ruth D. Searching for Marquette: A Pilgrimage in Art. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2013.

Walczynski, Mark. Jolliet and Marquette: A New History of the 1673 Expedition. Champaign, IL: 3 Fields Press, 2023.

Lea Flowers Baker

Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

Marquette Statue

Marquette Statue  Marquette-Joliet Expedition

Marquette-Joliet Expedition

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.