calsfoundation@cals.org

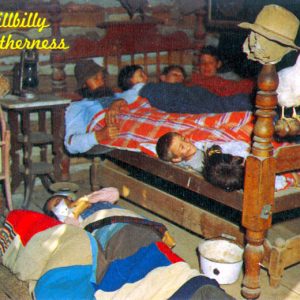

Hillbillies

The “hillbilly” has been an enduring staple of American iconography, and Arkansas has been identified with the hillbilly as much as, if not more than, any state. Despite the lack of scholarly consensus on the origin of the term—historian Anthony Harkins gives as the most likely explanation that Scottish highlanders melded “hill-folk” with “billie,” a word meaning friend or companion—there is no shortage of hillbilly images in American popular culture. Whether a barefoot, rifle-toting, moonshine-swigging, bearded man staring out from beneath a floppy felt hat or a toothless granny in homespun sitting at a spinning wheel and peering suspiciously at strangers from the front porch of a dilapidated mountain cabin, the hillbilly, in all his manifestations, is instantly recognizable. Wrapped up with the condescension in people’s common view of the hillbilly is a trace of admiration for what they perceive as his independent spirit and his disregard for the trappings of modern society.

In modern American popular culture, the term hillbilly is often used interchangeably with other epithets for poor white people such as “redneck,” “cracker,” or “white trash.” But, throughout much of the twentieth century, the word hillbilly conjured a character whose geographic origins were more narrowly defined. Referring to poor, uneducated whites, generally in the Appalachians or the Ozarks but not always confined to these two Southern highland regions, the hillbilly made his literary debut only in 1900, in the pages of the New York Journal. The term was likely in common use, however, in the rural South by the late nineteenth century. Although the subjects of the Journal piece were residents of the Alabama hills, the first scholarly use of the term appeared four years later in a study of Arkansas Ozarks dialect. One can argue that “hillbilly” and Arkansas have been synonymous ever since.

The popularization of the term hillbilly might be a twentieth-century phenomenon, but the genealogy of the hillbilly icon stretches deep into Arkansas history, from Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s caustic descriptions of the Arkansas Ozarks’s earliest settlers to the late-nineteenth-century stories of Opie Read in his Arkansas Traveler. As Anthony Harkins notes, by the time of the Civil War, the word “‘Arkansas’ was becoming instantly recognizable shorthand for the half-comic, half-savage backwoodsman.”

This development had two primary causes: the proliferation of Arkansas stories written by southwestern humorists in the twenty-five years before President Abraham Lincoln’s election and the Arkansas Traveler legend, which spawned songs, dialogues, a musical, and two popular paintings. Among the southwestern humorists, none was more effective in crafting the image of the hillbilly’s ancestor than C. F. M. Noland and Thomas Bangs Thorpe (who wrote “The Big Bear of Arkansas”), both of whom contributed many stories and letters to the New York sporting periodical The Spirit of the Times beginning in the latter half of the 1830s. Noland’s rough-and-tumble frontier character Pete Whetstone provides one of the best examples of an early hillbilly type whose comic, ill-mannered backwardness is tempered by resourcefulness and wile.

In twentieth-century popular culture, some of the nation’s most recognizable hillbilly characters were from Arkansas or had Arkansas connections, including Arkansas comedian and actor Bob Burns, radio’s Lum and Abner (Arkansans Chet Lauck and Norris Goff), B-movie stalwarts Ma and Pa Kettle, and television’s The Beverly Hillbillies. In the late 1960s, Newton County became the site of one of the most ambitious attempts to market and profit from Arkansas’s and the Ozarks’s hillbilly image when a group of Harrison (Boone County) investors partnered with cartoonist Al Capp to build the Dogpatch USA, theme park, based on Capp’s long-running Lil’ Abner comic strip. Arkansas’s continuing efforts to shed its backward image led some in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and elsewhere to criticize the project as pandering to the nation’s negative perceptions of the state and its citizens and to cringe when former governor Orval Faubus, himself the subject of hillbilly stereotyping, once served as the park’s general manager.

Although the crass stereotyping of Al Capp and Dogpatch, U.S.A., rankled many Arkansans, others coopted the term “hillbilly” and wore it as a badge of honor. In the 1970s, members of Arkansas band Black Oak Arkansas, along with other groups of the era such as Missouri’s Ozark Mountain Daredevils, proudly proclaimed their music “hillbilly rock.” Many people in Arkansas and around rural America had even earlier embraced the corn-pone antics of The Beverly Hillbillies. This willingness to simultaneously exercise self-deprecation and express cultural pride—long evident in Arkansas humor and in the interaction of Arkansans with outsiders—spurred interest in the redneck craze of the 1990s and continues to offer many Arkansans a sense of empowerment when dealing with a term often used with derision.

Arkansas’s most blatant symbol of the hillbilly stereotype, Dogpatch, went out of business in the early 1990s, but any hopes that the state finally had outrun its hillbilly image came crashing down during the 1992 election and early presidency of Bill Clinton. Metropolitan reporters and cartoonists joined Ross Perot in hammering Arkansas and its governor, and, despite his Yale law degree and his status as a Rhodes Scholar, Clinton often was depicted as the yokel leader of a hillbilly state. Almost 175 years after Schoolcraft first expressed disdain for the backcountry denizens of Arkansas territory, the little state of Arkansas, and supposed hillbillies everywhere, continued to absorb the barbs of more urbane visitors and pundits.

For additional information:

Blevins, Brooks. Arkansas/Arkansaw: How Bear Hunters, Hillbillies, and Good Ol’ Boys Defined a State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

———. Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Harkins, Anthony. Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Perkins, J. Blake. Hillbilly Hellraisers: Federal Power and Populist Defiance in the Ozarks. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

———. “Mountain Stereotypes, Whiteness, and the Discourse of Early School Reform in the Arkansas Ozarks, 1910s-1920s.” History of Education Quarterly 54 (May 2014): 197–221.

Williamson, J. W. Hillbillyland—What the Movies Did to the Mountains and What the Mountains Did to the Movies. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Brooks Blevins

Lyon College

Hillbilly Image

Hillbilly Image

I am the family historian for our Biles line. You missed the earliest origins of the term hillbilly. The family/clan name Biles means those living on top of a hill or promontory. This name appears in many cultures, and the various Biles families are not necessarily related. The Italians pronounce Biles as “bee lays,” which leads to hillbillies. My roots are Scots-Irish and our Biles line originated in Scotland as hill-folk/hillbillies.

There are multiple online references as to the meaning of the Biles name and its presence throughout the Celtic lands. When one of my cousins who is living in Italy pointed out how the Italians pronounce her last name, I saw the correlation with “bee-lays” living on a hill or promontory with the term hillbillies. Perhaps coincidence, but I doubt it. The high concentration of Scots-Irish living on the mountains in the Appalachians here, as well as my Biles relatives spread throughout these mountains, lends itself to this connection.

One reference to this is “The Biles-Byles Family, How Green Was Our Valley” by Bryan Biles. I was present when Bryan was given some of our family history from my predecessor historian. There are known errors in this reference, but it is a start. And no known relation to any Hatfields or McCoys.