calsfoundation@cals.org

Dyess (Mississippi County)

aka: Dyess Colony Resettlement Area

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º35’23″N 090º12’48″W |

| Elevation: | 223 feet |

| Area: | 0.96 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 339 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporated: | January 9, 1964 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

433 |

446 |

466 |

515 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

410 |

339 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the most famous “resettlement colonies” for impoverished farmers during the Great Depression was in Dyess (Mississippi County). The Dyess Colony became one of the most well known because one of its early residents was singer Johnny Cash. National attention focused on Arkansas when First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the community in 1936. Although smaller now and no longer a government project, Dyess still attracts tourists to northeast Arkansas.

While the Roaring Twenties had a euphoric effect on much of the nation, the agricultural economy of Arkansas did not share in the prosperity. By the end of the 1920s, one disaster after another devastated the small independent farmers of the state. The Flood of 1927 was followed by drought. The stock market crash of 1929 was followed by bank failure. By the end of 1930, approximately two-thirds of Arkansas’s independent farmers lost their farms and fell into tenancy.

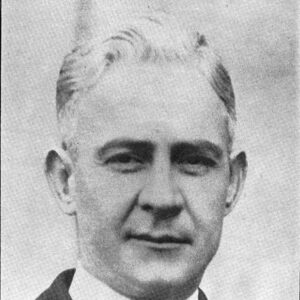

The election of Franklin D. Roosevelt as president in 1932 led to new programs that worked to pump life into the nation’s economy, especially in places like Arkansas, which was among the states hardest hit. Such agencies as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) tried to ease the poverty of destitute farmers and sharecroppers. William Reynolds (W. R.) Dyess, a Mississippi County plantation owner, was Arkansas’s first WPA administrator. He suggested an idea to Harry Hopkins, special advisor to Roosevelt, in which tenant farmers could have a chance to own their own land. FERA would purchase 16,000 acres of uncleared bottomland in Mississippi County, which was rich and fertile though also swampy and snake infested, and would open the land, with $3 million in federal aid, as a “resettlement colony” to homesteading families, who would each have to clear about twenty acres of land for cultivation.

In May 1934, “Colonization Project No. 1” was established in southwestern Mississippi County near the current Arkansas Highway 297. Named for W. R. Dyess, the rural cooperative community was to be assisted by the federal government in helping its farmers have a reasonable chance for success. Some 1,300 men whose names were taken from the relief rolls of Arkansas began construction on May 22, 1934. They had been brought to Mississippi County and put to work building roads and houses. The colony was laid out in a wagon-wheel design, with a community center at the hub and farms stretching out from the middle. The roads leading out were simply numbered rather than named, as in “Road 14.” The men dug ditches to drain the land, and they built 500 small farmhouses. Each house had five rooms with an adjacent barn, privy, and chicken coop. The houses were white-washed clapboard, each having two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen, and a dining room, plus a front and back porch. Apart from these improvements to the land, the colonists were expected to do the rest themselves.

Like most New Deal housing projects, it was intended for white people only.

Interviewers from the government were sent to each county in Arkansas to evaluate volunteers, who had to fill out a six-page application form. Families with a farming background from the state’s relief rolls were selected through the application process, which attracted thousands of hopeful. Criteria for the all-white community included that applicants be destitute from the economic crisis, come from the lowest poverty level, be of “good moral background,” and that husband and wife each have the physical ability to clear the land and farm their acreage. Each farmer would draw a subsistence advance to buy twenty to forty acres of land and one of the new five-room houses, plus a mule, a cow, groceries, and supplies until the first year’s crop came in. All were expected to pay back the advance. The town would operate as a cooperative in which seed was purchased and crops were sold communally. The families would then receive a share of any profits from the crops and other Dyess businesses, such as the general store and cannery. A local scrip called “doodlum” would be used as currency, and after about three years, when the land had been cleared and the fields were producing, the “licensee” would receive a deed to the house and land after repaying the advance.

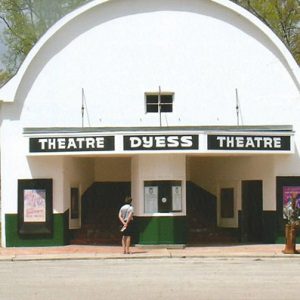

In the autumn of 1934, the first of about 500 families arrived and began clearing the land; they cut down trees and blasted stumps to farm cotton, corn, and soybeans, along with maintaining a pasture for livestock. In time, along with the administration building, the town center included a community bank, beauty salon/barbershop, blacksmith shop, café, cannery, cotton gin, feedmill, furniture factory, harness shop, hospital, ice house, library, theater, newspaper (the Colony Herald), post office, printing shop, service station/garage, sorghum mill, and school. Members of the colony often performed community tasks on a cooperative basis, though the farms were worked individually.

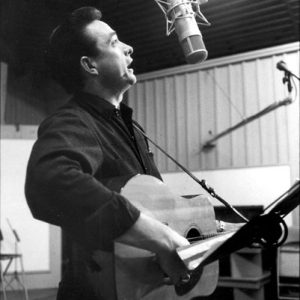

In 1935, the parents of future music legend Johnny Cash settled there. Ray Cash and Carrie Rivers Cash were one of five families selected from Cleveland County. Called “John” by friends and “J. R.” in his high school yearbook, young Cash attended Dyess High School, graduating in 1950 as class vice president. Future radio personality Harold Gene Williams, who would go on the promote Johnny and his brother Tommy, also attended school there. Johnny Cash visited the community throughout his career in show business. In 2004, the Dyess Colony was once again in the spotlight as a movie company arrived to film a portion of Walk the Line, a movie about Cash’s life.

Colonization Project No. 1 was incorporated in February 1936 as the Dyess Colony, one month after the death of W. R. Dyess in an airplane crash. Because of its size, cooperative nature, and impetus from the federal government, Dyess attracted the attention of the national news media. On June 9, 1936, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt paid a visit, making a speech at the administration building, having supper at the Dyess Café, and shaking hands with locals for several hours. At the time of her visit, there were about 2,500 residents of the colony.

The white-columned administration building, which resembles a Southern plantation house, became a symbol and focal point of controversy in 1940 when the colony was placed under the management of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) due to a political dispute between the state and federal governments. Farmers felt they had become subservient to larger entities, much like the former plantation system, undermining their independence. With the coming of World War II, about half the residents left Dyess for war work, never to return. From its 1936 high point of 2,500 residents, only 515 remained at the time of the 2000 census.

In 1964, Dyess was incorporated as a municipality and is today governed by a mayor and board of aldermen. A reunion is held each summer for former Dyess residents and their descendants, with hundreds of people usually in attendance. Tourists continue to visit Dyess to see the place that was home to Cash during his youth. In 2011, Arkansas State University in Jonesboro (Craighead County) purchased Cash’s boyhood home for a reported $100,000 and restored the house to serve as a museum; the Historic Dyess Colony: Boyhood Home of Johnny Cash opened to the public on August 16, 2014. The Johnny Cash Heritage Festival began in 2017.

The administration building and school serve as a community center, with the administration building being listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 1, 1976. What began as an experiment in resettlement during a time of desperation has transformed itself into a stable, though substantially smaller, community. It also lives on through the legacy of Cash’s song, “Five Feet High and Rising,” based on his experience of Dyess being evacuated during the flood of January 1937, as well as contemporary country singer Buddy Jewell’s song, “Dyess, Arkansas,” in which he sings, “I know there’s bigger cities, but there ain’t no better town.”

For additional information:

Cash, Johnny. Cash: The Autobiography. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1997.

Hawkins, Van. A New Deal in Dyess: The Depression Era Agricultural Resettlement Colony in Arkansas. Expanded ed. Jonesboro, AR: Writers Bloc, 2020.

Henson, Everett Dewey. “Memories of Dyess Colony.” Delta Historical Review 2 (Summer 1990): 3–21.

Historic Dyess Colony: Boyhood Home of Johnny Cash. http://dyesscash.astate.edu/ (accessed May 28, 2022).

Holley, Donald. “Trouble in Paradise: Dyess Colony and Arkansas Politics.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Autumn 1973): 203–216.

———. Uncle Sam’s Farmers: The New Deal Communities in the Lower Mississippi Valley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975.

Moufdi, Ismail. “Comparing and Contrasting the Construction of Identity by Residents of Dyess Colony and the Rohwer Resettlement Camp.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2021.

Pittman, Dan W. “The Founding of Dyess Colony.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Winter 1970): 313–326.

Smith, Fred C. Trouble in Goshen: Plain Folk, Roosevelt, Jesus, and Marx in the Great Depression South. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014.

Woodward, Colin Edward. Country Boy: The Roots of Johnny Cash. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Canning at Dyess

Canning at Dyess  Johnny Cash Boyhood Home

Johnny Cash Boyhood Home  Johnny Cash

Johnny Cash  Rosanne Cash

Rosanne Cash  Colony Herald

Colony Herald  Dyess City Hall

Dyess City Hall  Dyess Theatre

Dyess Theatre  Dyess Administration Building

Dyess Administration Building  Dyess Buildings

Dyess Buildings  Dyess Colony

Dyess Colony  Dyess Hospital

Dyess Hospital  Dyess School

Dyess School  W. R. Dyess

W. R. Dyess  Sharecropper House

Sharecropper House

I had the honor of visiting Dyess on November 25, 2022. The history of this community is very interesting. People now days couldn’t survive if they had to work as hard as these farmers worked. I know they had a tough life, but it almost sounds magical when you think of how the families worked so hard yet had so many wonderful memories. I hope to return next year with my family.

My grandparents, Cora and Lawrence Gordey, were relocated to Dyess Colony during the hard times of the Depression. With seven children to house, feed, and clothe, their lives were not easy. My mother, Earlyne Gordey, attended school at Dyess, as did her brothers, Malcomb, H. V., Eddyce, and his twin sister, Eddye. My mother died in 1963 in Fort Smith, and only one of the seven children of the Gordey clan is alive today. My uncle Mac, or Malcomb, died on February 27, 2008, in Fort Smith. The surviving uncle, Bill Gordey, lives in Greenwood, Arkansas. As children growing up, we were fascinated to know some of the antics of these kids in Dyess, but we were more fascinated with the story of Rosie, our grandmother’s pet raccoon, who was treated as one of the children. She ate at the table, washing her food in a special little dish, and basically had the run of the house. I guess when you have seven children, what is one more? The tragic ending of the story is that when they were moved out because of the flood, Rosie was left behind, and when they returned to get their household goods, sweet Rosie was found dead. This story would always reduce us to tears. We also were fascinated that our uncles knew the Cash brothers, and we would beg for stories about Johnny Cash in particular, although it seems they told more stories about some of the others in the Cash family. Many in our family have visited the colony or the city of Dyess. I would like to make a trip there when time permits.

I was raised at Dyess Colony. My parents, Hersh Henson and Nancy Kinder, moved to Dyess in 1936. Mother left Dyess in 1961. My wifes parents left in 1989. I have been gathering material on the beginning of Dyess for years, and I have a private website DYESS COLONY by MyFamily.com. I have material from the beginning and for as long as it was in government control on my website. I am in contact with people who grew up at Dyess and who visited their grandparents at Dyess. I hope to publish a book about Dyess. I am very proud that my parents were chosen to be a part of Dyess. To come to Dyess, you had to live in Arkansas, be in good health, be a married couple, be of good moral character, be on some kind of government relief program, have a farming background, and be poor.

This is truly the best article that I have read about Dyess, Arkansas. My grandparents are one of the original families of Dyess. This article is as close to the stories that have been passed down in my family as I’ve seen. Thank you for the work that you have done. I am the daughter of J. E. Huff.