calsfoundation@cals.org

World War II Prisoner of War Camps

aka: Prisoner of War Camps (World War II)

aka: Prisoners of War Camps (World War II)

aka: POW Camps (World War II)

During World War II, the United States established many prisoner of war (POW) camps on its soil for the first time since the Civil War. By 1943, Arkansas had received the first of 23,000 German and Italian prisoners of war, who would live and work at military installations and branch camps throughout the state.

The presence of POW camps in the United States was due in part to a British request to alleviate the POW housing problems in Great Britain. Initially, the U.S. government resisted the idea of POW camps on its soil. The huge numbers of German and Italian POWs expected to occupy the camps created many problems for the federal government and the military. The military did not have the experience or manpower to maintain camps with large POW populations. Most of the skilled military personnel fluent in German and Italian were fighting overseas. Government officials feared that housing so many prisoners could create security problems and heighten fears among Americans at home.

Establishing and managing POW camps in the United States was challenging on many levels, but organizing prison camps overseas created problems of its own. Supervising large groups of prisoners in Europe while adhering to the POW treatment policies established by the Geneva Conventions diverted food, transportation, and medical resources from the American war effort overseas. Eventually, the United States reasoned that keeping prisoners of war in the United States would be an efficient use of military resources.

To alleviate some of the security concerns in metropolitan areas and calm citizens’ fears, the United States housed prisoners in military installations and federal facilities throughout the South and Southwest. About 425,000 captured Axis troops were sent to the United States for internment in more than 500 camps. Nearly 23,000 captured troops, mostly Germans and Italians from Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, were sent to POW camps in Arkansas. Camp Robinson in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), Camp Chaffee in Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and Camp Dermott in Dermott (Chicot County) were the state’s primary centers for Germans. The remote locality of Camp Dermott in southeast Arkansas, previously the Jerome Relocation Center for Japanese Americans, made it the perfect site to house German officers, while Camp Monticello in Drew County housed Italians, as did a branch camp in the Magnolia (Columbia County) area. The Stuttgart Army Air Field in Stuttgart (Arkansas County) hosted German and Italian POWs.

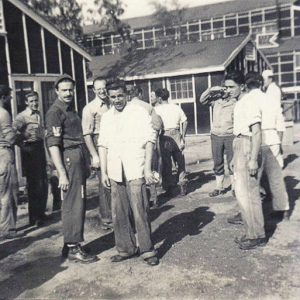

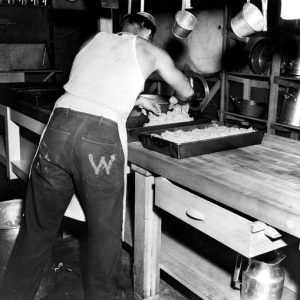

Camp Robinson was regarded nationally as a model camp. Living conditions in the camps were pleasant under the circumstances and included barrack housing, recreational activities, and creative and educational opportunities. Soccer was a popular sport among prisoners. POWs also performed theatrical plays and musical concerts. But it was not all fun and games. The POWs were required to work in and around the camp, earning eighty cents a day for their labor. Their duties included working in the camp cafeteria, in grounds maintenance, and on local construction projects. POWs could use their wages in the camp store to buy toiletries, candy, cigarettes, and even beer.

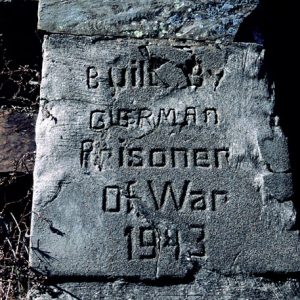

Many young men left Arkansas during World War II to serve in the military or find jobs in defense-related industries. Consequently, a labor shortage occurred in the farming and timber industries. To alleviate these shortages, prisoners supplemented the farm and labor forces at branch camps throughout Arkansas, mostly in the Delta and southern regions. In many cases, facilities from the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) served as barracks for the POWs at the branch camps. Each day, trucks of prisoners were transported to farms and timber sites to chop cotton, cut wood, and perform other chores to help stabilize the economy. Prisoners at Camp Hot Springs, for example, worked in local hotels and built structures at Lake Catherine State Park, among other assignments.

There were few escape attempts because of the remote location of the state. Most POWs resigned themselves to a relatively comfortable existence in the camps. This lifestyle caused many citizens to accuse the military of coddling the enemy. Americans were subject to rationing of food and other items, while POWs were provided a steady diet of good food and access to many name-brand items, such as cigarettes, that were unavailable to the general population. Additionally, many Americans whose relatives were killed or captured overseas were hostile to the prisoners.

To ease the transition between the period of civilian labor shortage and the return of U.S. soldiers, several POW camps remained in operation for a year after the war. Eventually, the camps were dismantled around the summer of 1946, and the prisoners were allowed to return to Europe. The fair and kind treatment experienced by German and Italian prisoners had a lasting impact on them. After repatriation, many former prisoners returned to the United States to launch professional careers or to renew acquaintances with their former captors.

For additional information:

Akins, Jerry, and Sue Robison. “The Task Performed by the Organization: German POWs at Chaffee, Part One.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 47 (April 2023): 8–15.

Cash, Taylor. “From Jerome to Dermott: Comparing the Treatment and Experiences of Japanese Americans and German Prisoners of War in Arkansas During World War II.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2022.

Evatt, Anna R., and Phillip Bruce McMath. “Friedenstal: A Historic Archeological Investigation of a Former Prisoner of War Camp.” Pulaski County Historical Review 60 (Summer 2012): 51–60.

Faust, Kate. “Remembrances of the Prisoner of War Camp in West Helena, Arkansas.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 16 (September 1978): 31–39.

Honnoll, W. Danny. “The Prisoner of War Camp at Jonesboro (Located at the Former Civilian Conservation Corps Camp Site).” Craighead County Historical Society Quarterly 57 (April 2019): 17–25.

Krammer, Arnold. Nazi Prisoners of War in America. Chelsea, MI: Scarborough House, 1996.

Page, Bert,and Ken B. Harper. “Achtung! WWII German POWs in Pope County.” Pope County Historical Association Quarterly 45 (July and December 2011): 10–12.

“Pictorial of German POWs at Camp Robinson during WWII.” Arkansas Military History Journal 13 (Winter 2019): 17–21.

“Prisoners of War at Camp Robinson—A Document.” Pulaski County Historical Review 39 (Winter 1991): 74–78.

Pritchett, Merrill R., and William L. Shea. “The Afrika Korps in Arkansas, 1943–1946.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Spring 1978): 3–22.

Schnedler, Jack. “Comfortable Confinement.”Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 12, 2013, pp. 1H, 6H.

Shea, William L., ed. “A German Prisoner of War in the South: The Memoir of Edwin Pelz.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Spring 1985): 42–55.

Smith, Calvin C. “The Response of Arkansans to Prisoners of War and Japanese.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 53 (Autumn 1994): 340–66.

Voss, Larry D. “The Prisoner of War Camps in Northeast Arkansas.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 7 (Summer 1969): 11–14.

Ward, Jason Morgan. “‘Nazis Hoe Cotton’: Planters, POWs, and the Future of Farm Labor in the Deep South.” Agricultural History 81 (Fall 2007): 471–492.

World War II Prisoner of War Records: Records of Prisoner of War Camps in Arkansas, 1943–1946. University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections. https://uark.as.atlas-sys.com/repositories/2/resources/33 (accessed December 30, 2020).

Michael Bowman

Arkansas State University

Military

Military World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Camp Monticello Barracks

Camp Monticello Barracks  Camp Monticello POWs

Camp Monticello POWs  German POW at Camp Chaffee

German POW at Camp Chaffee  German POW Camp

German POW Camp  POW Camp in Earle

POW Camp in Earle  POW Stone

POW Stone

Camp Magnolia, Civilian Public Service Camp Number 7 for Conscientious Objectors in Magnolia, Arkansas, reopened for a short time in 1945 in order to house Italian prisoners as a branch of Camp Monticello. The conscientious objectors were removed and the camp closed in October of 1944, then it reopened for a short period starting around the first of June 1945 in order to house Italian POWs. Once all the POWs had been removed the buildings were put up for auction in March of 1946. There were several escapes from this facility during that time. There is a mention of Camp Magnolia as a branch of Monticello in the University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections World War II Prisoner of War Records, 1943-1946. The camp at Magnolia was heavily damaged by a 1944 tornado, but apparently not all of it was completely destroyed. A few buildings may have remained intact, but they must have at least rebuilt the barracks. Newspaper articles reporting on the tornado specifically stated that the barracks were destroyed, but when the buildings were auctioned off in March of 1946, two large barracks were included.

My father was a German POW in Camp Robinson. He worked in the kitchens and spoke about being very well treated there. He got paid and bought bits of Mexican silver. He had visits and presents from his American uncle from New York who had come to the States in the 1930s (although a treasured pair of gloves he received were “confiscated” as the POWs were being shipped back to Europe). He also told me that at some time he worked picking cotton. He said some POWs worked in the local cotton mills, but when there were a number of “suspicious” fires, they were not allowed to work in the mills anymore. The fires continued, however. My dad told me that some of the cotton-picking prisoners were breaking off match heads and stuffing them in the bales. When the cotton reached the cotton gins, the matches ignited. They were just wild kids. My dad had his twenty-first birthday there. The POWs were actually kept in camps in England for another three years after the war had ended.

I grew up in southwest Arkansas. I was born in Nashville in Howard County on July 27, 1934, and recall the prisoners working in the timber industry during WWII. I dont recall ever seeing one of them but we knew they were in the area between Nashville and Murfreesboro. On July 4, 1944, I recall having a couple of nickels and wanted to buy a Coke. There were none to be found. We were told that all were taken to the Germans that week. There is a Coca-Cola plant in Nashville.

My father, L. T. Edwin F. Roble, was one of the officers in charge of the POW camp at Ft. Chaffee. My late brother Jack was born at Fort Smith, Arkansas, in 1943. I came across your site while researching my father’s military career, which spanned thirty-three years. He was called to active duty from his National Guard unit stationed in Blairsville, Pennsylvania. He took his four kids and wife to Arkansas, where his fifth child was born.

My father lived and worked on the Stuttgart Air Base as a civilian in the fire department during WWII. He lived there again and worked on the farm there after the war. He made clear statements to me that there were German POWs kept there. I assumed they had something to do with providing information regarding German fighter or bomber operating policies which would help the training of our forces there, but this is speculation.

In 2001, I hosted an Austrian librarian who was on an exchange. When asked what he wanted to see, he said, a cotton field. It turns out that his father was a conscript in the German army and had spent time in a POW camp in Arkansas. He said his father often spoke of the heat and dust. He hated picking plant wool, which is how the librarian described cotton. The Italian POW camps have not been very well studied, as far as I know. Prof. Bill Shea at UAMonticello has written and spoken on POW camps in Arkansas. He tells a really funny story about how the newly arrived Italian POWs at Monticello were disappointed that there were no mountains in Monticello. Also, they were downright offended when they went to the only music store in Monticello and could not locate any operas by Verdi.

I have a book from Arthur Schopnenhauer that belonged to my father, Siegfried Opitz; I started to research the internet about Dermott in Arkansas. The book is still with me. In the front page of the book is written: Siegfried Opitz 81 G-314-702-H, P.O.W. Camp Dermott Arkansas, Christmas (Weihnachten) 1949; I do not know much about this time. My father told me he was in the camp for two years, and it had a lot of benefits, such as learning, studying, sport. Many years later, my father returned to the USA. From 1978 to 1980 he lived with my mother in San Francisco working for the German Consulate. I want to say thank you for all you Americans did during during that war in the camps and that you saved my father’s life, as he was able to escape from the hand of the Resistance in South France and come to the USA. He was twenty-five years old. My father died in 2002 in Australia. I hope and I know that we never ever will have such bad times anymore in our world.

Was just reading your information about the prisoner of war camp in Jerome, Arkansas. I worked there from June 1945 to August 1945–was between semesters at college. I also lived in Jerome so was close to home. It was quite an experience. We worked with fifteen German prisoners doing their payroll. My boss was a German-American from New York. It was an experience you would not ever forget.

Im originally from Arkansas. I lived in Blytheville (Mississippi County) from 1946 until 1959. I am 70 years old. When I was about three or four years old, we lived on a farm that we rented from a man everyone called Mr. Eddie, at Armoral in Mississippi County. I dont remember too much about it because of being so young at the time, but we had a few German POWs working on the farm we rented. They used to play around and tease my brother and me, and pour water on our feet from the pump.

The reason I got interested in this was we had a movie at church that was about the POWs in Georgia and the miracle that happened on Christmas. I cant remember the name of it now, but it was very good. I thought everyone knew about the POWs that helped out the farmers, but it seemed that only one man from our church knew anything about it.

I think the guards were so excited when the war ended that they left a few things behind at our house. We had a canteen, a machete, a bayonet, and I think a metal plate that folded up to eat from. We still have the bayonet, and I dont know what happened to the other things over the years. Im going to write out as much information as I know and give the machete to my son, along with the information. I remember my brother and some friends playing with those things, but none of us ever got hurtthey were dangerous weapons!

My father, Grant Harold Collar Sr., was the farm manager for R. C. Langston who owned a plantation at and around Rosa, AR, a few miles north of Luxora. He was half-German and had studied German at Arkansas State Teachers College and had a working knowledge of the language. He was one of the first to “employ” the German POWs to work on the Langston farm. He discovered quickly that a very small lunch was sent out from the camp–too small for people to do a lot of work. We had a company store at Rosa, and Dad would take a whole bologna, bread, crackers, etc., out to the field at lunchtime each day. He developed a relationship with some of the Germans that lasted for decades through letters. I am proud of my dad for treating them like men. They responded by never giving a minute’s trouble and working diligently.