calsfoundation@cals.org

Maud Robinson Crawford (1891–1957)

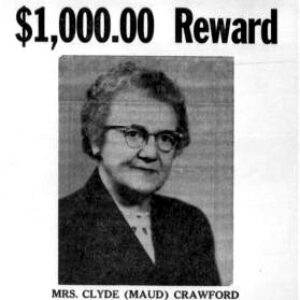

Maud Robinson Crawford, a lawyer with the Gaughan, McClellan and Laney law firm in Camden (Ouachita County), mysteriously disappeared from her stately Colonial home on Saturday night, March 2, 1957, at age sixty-five. U.S. Senator John L. McClellan, a former partner in the law firm, was at the time of her disappearance the chairman of a high-profile Senate investigation into alleged mob ties to organized labor. The disappearance of Sen. McClellan’s former associate was international news, a first assumption being that she had been kidnapped by the Mafia to intimidate the senator. When no ransom note appeared, however, the theory was rejected by law enforcement. No body was ever found, and the case was never solved.

Maud Robinson was born on June 22, 1891, at Greenville, Texas, the oldest of four children of John W. “Jack” Robinson and Ida Louise Faucett Robinson. Her mother died when she was nine years old, and she was raised by her grandmother, Mary Louise Faucett Ritchey, who operated a boarding house with her husband, Thomas, in Warren (Bradley County). In 1911, Robinson graduated from Warren High School as valedictorian of her class. She attended the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) for the 1911–12 school year. On December 7, 1925, she married Clyde Falwell Crawford, a young man from a pioneer Camden family. They had no children.

Maud Crawford began her career in 1916 as a stenographer at the Gaughan law firm in Camden. In 1927, only ten years after women were first allowed to practice law in Arkansas, she “read for the law,” which meant that she had acquired legal knowledge without attending law school and was allowed to take the bar exam. She took the exam with University of Arkansas School of Law graduates and passed first in the class. She excelled in abstract examination and title work during the south Arkansas oil boom of the 1920s through the 1950s, when she disappeared.

Crawford was active in civic affairs. She was the first woman elected to the Camden city council, serving from 1940 to 1948. In 1942, she was a founder of Arkansas Girls State, a program making it possible for high school girls to go to Little Rock (Pulaski County) for a week each year to learn how state government works. She served as one of the program’s eight counselors every year from 1942 until her disappearance in 1957. She was elected president of every women’s civic club for which she was eligible in Camden: the Business and Professional Women’s Club, the American Legion Auxiliary, and Pilot Club International, sister club of Rotary International. In 1954, the Pilot Club named her “Woman of the Year.” In 1955, Camden won an achievement award for “Outstanding Community Improvement” in the state, and Crawford was chosen to go to Little Rock to give a speech and accept the award on behalf of the community.

The night she disappeared, her husband, Clyde, had gone to a movie. When he returned home at about 11:00 p.m., all the lights were on inside and outside the house, his wife’s car was in the driveway where she always left it, the television was on in the living room, her purse was on a chair with $142 cash in it, and her guard dog was undisturbed. When she had not returned home by 1:00 a.m., he drove to local cafes and then past homes of some of her friends to see if lights were on. He flagged down two policemen to ask if there had been a car accident that might explain her absence. At 2:00 a.m., he drove to the police station and reported her missing.

The next day, the police and local citizens began an extensive search for her body, but none was ever found. Two weeks after her disappearance, the local newspaper, The Camden News, reported that, according to Police Chief G. B. Cole, the investigation was “stalemated” and quoted Ouachita County Sheriff Grover Linebarier as saying, “We have not turned up a single clue.” The newspaper declared the widely reported case “at a dead end.”

In 1969, the Probate Court of Ouachita County legally established Crawford’s death, stating in part: “It is the finding of the Court that Maud R. Crawford is deceased and has been dead since March 2, 1957, as a result of foul play perpetrated by person or persons unknown.”

In 1986, twenty-nine years after Maud Crawford’s disappearance, an eighteen-article investigative series by Beth Brickell was published on the front page of the Arkansas Gazette. The series implicated a deceased Arkansas State Police commissioner, Henry Myar “Mike” Berg, in the case. Berg, a Camden multimillionaire businessman, was appointed to the Arkansas State Police Commission in 1955 by Governor Orval E. Faubus. Berg served as a commissioner until shortly before his death in 1975.

After the first article was published linking Berg to Crawford’s disappearance, Berg’s widow, Helen Berg, threatened the newspaper with a lawsuit if it published subsequent articles. After examination of the reporter’s extensive records by the Gazette’s attorney, Phil Carroll of the Rose Law Firm in Little Rock, Gazette publisher Carrick Patterson proceeded to print the complete series over a five-month period. A lawsuit against the newspaper was never brought by the Berg family.

The series revealed sensational new information from Odis A. Henley, the original State Police detective on the case who, at the time of the reporter’s investigation, was a deputy sheriff at El Dorado (Union County). Henley was quoted as saying that he was assigned to the case the day after Crawford disappeared and that he found a clue and other evidence regarding the disappearance. According to Henley, he reported to the captain of the State Police Criminal Investigation Division, Alan R. Templeton, that all of his findings pointed to State Police Commissioner Mike Berg having had Crawford murdered. According to Henley, he was told, “There’s too much money involved,” and he was taken off the case and was told to leave his reports at the headquarters. The next time Henley went to Little Rock, all of his files had disappeared.

The Gazette series also revealed for the first time a motive for the murder of Crawford. The motive involved two fraudulent deeds that the reporter located in the Hempstead County Courthouse. A first deed transferred large timber assets belonging to Berg’s aunt—Rose Newman Berg, an elderly woman declared incompetent in 1955 by the Ouachita County Court—to a timberman, Hugh Moseley, who worked for Mike Berg. On the same day, a second deed transferred the same assets from Moseley to Mike Berg. The newspaper series quoted former state attorney general Jim Guy Tucker as saying, “If I wanted to prove that Mike Berg defrauded Rose Berg, these deeds would be powerful evidence.”

According to Henley, one or two months before Crawford disappeared, she went to Berg’s office and angrily accused him of stealing timber from Rose Berg’s estate. Crawford was Rose Berg’s attorney and had been appointed her personal guardian by the court when Rose was declared incompetent. At an earlier time, Crawford had drawn up a will for Rose leaving her estate, valued in excess of $20 million, to three out-of-state nieces on her side of the family: Jeannette Newman Simpson, Marian Newman Peltason, and Lucille Newman Glazer. Mike Berg was not named in the will.

According to the nieces, shortly before Crawford disappeared, she told them she “had the goods” on Mike Berg and that, upon her retirement, she intended to bring a lawsuit against him that would expose a pattern of fraudulent deeds designed to thwart Rose Berg’s will. In addition to the timber deeds, earlier deeds had been discovered at the Ouachita County Courthouse transferring assets over a period of years from Rose Berg to Mike Berg. One deed, eight pages in length with a shaky Rose Berg signature, conveyed to Mike Berg 21,211 acres of timberland in fifteen counties, as well as sixty-two city properties and an estimated 150 producing oil royalties.

When Crawford disappeared, Rose Berg’s will disappeared. Mike Berg succeeded in getting all of Rose Berg’s estate. In a settlement one year after the disappearance, Berg granted $187,000 to each of Rose Berg’s three nieces in exchange for a relinquishment of all claims to their aunt’s estate.

As a result of allegations in the investigative series, the twenty-nine-year-old case was reopened by the south Arkansas prosecuting attorney, Bill McLean, based in El Dorado. McLean obtained a subpoena to interview Mike Berg’s bodyguard, Jack Dorris, whom Henley believed was involved with Berg in Crawford’s demise. Dorris was dying of cancer at the time. When McLean arrived at the Dorris home for the interview, Dorris was surrounded by family members and the current Ouachita County sheriff, Jack Dews, a cousin of another Mike Berg employee who was angry that McLean was operating in his county without his cooperation. According to McLean, Dorris was “groggy and couldn’t talk.” Dorris died seven hours later.

Former governor and U.S. senator Dale Bumpers added a curious footnote to the Maud Crawford–Mike Berg saga in an oral history with journalist Ernest Dumas in 2002 for the UA’s David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History. Bumpers recalled that a few days after he became governor in 1971, he returned to the Governor’s Mansion from the capitol to find a small package from Berg, who hoped to be reappointed to the Arkansas State Police Commission, as his term was expiring. Bumpers said Berg “wanted to be reappointed to the Police Commission worse than he wanted to go to heaven.” Inside the package was an expensive Rolex watch with the price tag of about $800 still attached. Bumpers said he returned the watch with a note thanking Berg but noting that he was returning all gifts of any size. Sometime later, a state trooper in the State Police Criminal Investigation Division told Bumpers that a new inmate at the state penitentiary, obviously hoping for some amelioration of his sentence, volunteered to prison officials that Mike Berg had tried to hire him to assassinate Bumpers but that he had committed another crime that landed him in prison before he could carry out the assassination. The lawman asked Bumpers what he wanted done. Bumpers said he replied that someone in law enforcement should go to Camden and tell Berg that if anything happened to the governor or any member of his family, they were coming for Berg. Bumpers said he never heard anything from Berg or the State Police after that. Berg remained on the commission until January 1975, when Governor David Pryor replaced him.

For additional information:

Brickell, Beth. “Mystery at Camden.” Eighteen-part series. Arkansas Gazette, July 25, 30, and 31, 1986; August 1, 3, 7, 11, 13, and 22, 1986; September 21, 1986; October 19, 1986; November 9, 12, and 23, 1986; December 21, 22, 23, and 24, 1986. Beginning on p. 1A each issue.

Beth Brickell

Luminous Films Inc.

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Mike Berg

Mike Berg  Maud Crawford

Maud Crawford  Maud Crawford

Maud Crawford  Maud Robinson Crawford Reward Poster

Maud Robinson Crawford Reward Poster  John McClellan and Robert Kennedy

John McClellan and Robert Kennedy

Mike Berg eventually faced the Judge of all judges. He was served justice for eternity.

This story fascinates me. Such a big mystery for a small southern town. It saddens me that such a prominent figure in the town was not given justice to have her disappearance properly and professionally investigated by the FBI, as the local authorities were not trained or perhaps were too afraid to seek the truth.

I look forward to going to Camden this summer to see her home and reflect on the fact that money stood in the way of truth.