calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas State Bank

The Arkansas State Bank (1836–1843) was one of two banks created by the newly formed Arkansas state legislature. It provided some funding for commercial projects, though most of its funds facilitated land sales. Its greatest legacy, however, was saddling the new state government with a burdensome debt and instigating several accounts of political corruption. In the end, the bank’s failure jeopardized both public and private banking in Arkansas due to the public outcry against its operation.

Banking was one of the most prominent political issues of the early nineteenth century. Waves of banking mania spread across the country as advocates sang the praises of increasing available currency and spurring on economic development. On the western frontier, demands for banks ran high as settlers sought capital with which to make their start. Planters especially called for the erection of banks because their plantations required lots of capital for labor and supplies, not to mention the need to clear vast amounts of land. Arkansans were among the most robust of antebellum Americans in their demand for banks as banking became an early concern for legislators. Even in the territorial period, several prominent politicians and planters called for the creation of a state bank, which would receive the support of the legislature in hopes of ensuring financial stability and providing capital.

The first state constitution included a provision for the creation of two banks. One, the Arkansas Real Estate Bank, would facilitate agricultural development. The other would serve the general public and become the depository for state funds. The Arkansas State Bank received much attention in the early days of statehood from both politicians in the legislature as well as planters and newspaper editors.

Both the Real Estate Bank and the State Bank garnered overwhelming support from Democrats and Whigs. Typically, Democrats opposed federal banking, but they were stalwart supporters of state banking. The Whigs supported nearly all banks. The State Bank’s legislative supporters, led by John Ringgold of Batesville (Independence County) and Chicot County planter Anthony H. Davies, chartered the Arkansas State Bank in 1836. Few opposed its creation, and fewer still of the bank’s detractors gained public office. The bank’s first president was Captain Jacob Brown, who was forced from office because he held a simultaneous position with the army while also trying to preside over the bank. Its directors were leading planters and businessmen: Edward Cross, David G. Eller, David Fulton, and William B. Wait. Also serving as a director was Chester Ashley, a prominent attorney and future U.S. senator. But it was State Treasurer William E. Woodruff who took the lead in raising capital.

Many state banks, including Arkansas’s, were capitalized by the selling of state-issued bonds to other banks or investors. In some cases, most of the assets of state banks existed in the form of other state bank notes. But according to the Arkansas State Bank’s charter, it could not begin operation until $50,000 of specie (commodity-based money) was raised or deposited. Further complicating the bank’s opening was the country’s economic condition. In 1837, the United States entered one of the worst and longest depressions of its history. Demand for state bonds ran low, and specie was increasingly scarce. In many ways, the depression resulted from state bonds and bank notes flooding—and inflating—the market because of bank mania. Above all, sufficient local demand for the State Bank did not arise, and few depositors sought the bank’s services. Most supporters believed funds could be gained by the sale of bank notes distributed by the federal government. In the mid-1830s, the federal debt was extinguished, and the federal government received more in revenue than it spent. Congressmen decided to distribute the surplus to the states—but as bank notes, not as specie. Arkansas officials hoped to sell the state’s portion of the notes to other banks for specie, but this proved virtually impossible.

In the spring of 1837, the Department of War commenced buying some state bonds, including $300,000 from Arkansas. Now that the bank had sufficient funds, it started distributing those funds to its branches. The charter allowed for branch banking, a notable innovation practiced across the South. The Arkansas State Bank had branches in Batesville, Fayetteville (Washington County), and Arkansas Post (Arkansas County), while the main office was in Little Rock (Pulaski County). The branches opened at different times between January 1838 and January 1839, depending upon available funds and office supplies.

The branches and the Little Rock bank followed a similar fiscal pattern, as loans were more important than deposits. Loans in the form of bank notes went to both individuals and government entities such as counties, and considerable expenses mounted for the construction of bank buildings and accoutrements. The requirement of paying specie for interest on the bank’s own bonds it issued to raise funds further complicated its operation. It took only about a year for the bank to cease redeeming its notes in specie, further depreciating the bank’s inflated notes.

By the early 1840s, many prominent Arkansans sought to cease making payments on the state bank bonds to remedy the situation. The major defenders of repudiation were prominent Whigs in Little Rock and supporters of the presidential ambitions of Kentucky statesman Henry Clay. While outright repudiation failed to materialize, the financial weakness of the State Bank and the Real Estate Bank continued. The Arkansas State Bank ceased operation in 1843.

Almost immediately, politicians and voters led by Governor Archibald Yell blamed not only the bank’s faulty and inflationary lending policy but the bank itself. Many blamed all banks. As a result, the first amendment to the state’s constitution forbade banks from operating in Arkansas. It gained voter approval in 1846. The banking crisis in Arkansas reflected the end of an era both nationally and locally. But while a private banking system rapidly developed elsewhere, Arkansas remained plagued by the lack of significant stores of capital, and the impact of the banking prohibition may never be truly known.

For additional information:

Schweikart, Larry. “Banking in Antebellum Arkansas: New Evidence, New Interpretations.” Southern Studies 26 (1987): 188–201.

Worley, Ted R. “The Arkansas State Bank: Antebellum Period.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Spring 1964): 65–73.

Carey M. Roberts

Arkansas Tech University

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Collins, Richard D'Cantillon

Collins, Richard D'Cantillon Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Politics and Government

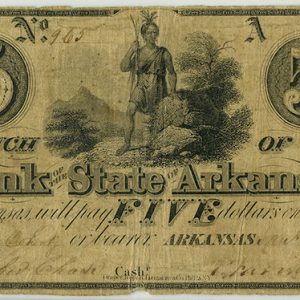

Politics and Government Arkansas State Bank Note, 1839

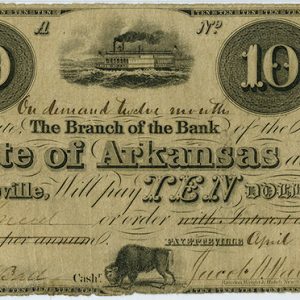

Arkansas State Bank Note, 1839  Arkansas State Bank Note, 1838

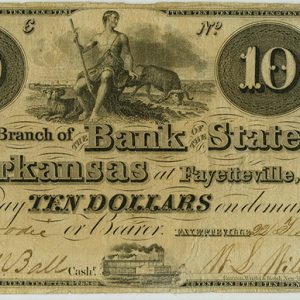

Arkansas State Bank Note, 1838  Arkansas State Bank Note, 1840

Arkansas State Bank Note, 1840

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.