calsfoundation@cals.org

Prohibition

Prohibition, the effort to limit or ban the sale and consumption of alcohol, has been prevalent since Arkansas’s territorial period. The state has attempted to limit use of alcoholic beverages through legal efforts such as establishing “dry” counties, as well as through extra-legal measures such as destroying whiskey distilleries. Since achieving statehood in 1836, prohibition has consistently been a political and public health issue.

As early as the 1760s, European settlers at Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) took steps to limit alcohol use by Quapaw Indians living in the area. When the area was under Spanish control, British traders successfully maneuvered to trade goods and spirits in Arkansas, plying the Quapaw with rum despite a Spanish law prohibiting the furnishing of alcohol to natives. The Spanish, in turn, often used alcohol as a diplomatic tool for settling disputes with Indians. By the early 1780s, Spanish-controlled Arkansas settled on heavily regulating the production and sale of alcohol, falling just short of outright prohibition.

Control of alcohol initially focused on consumption by Native Americans, but as Arkansas’s population began to increase, interest in prohibition began to widen. In the early nineteenth century, as Indians began resettling in present-day Oklahoma in accordance with the Indian Removal Act of 1830, a commander at nearby Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Lieutenant Gabriel Rains, organized a sting operation to disrupt the widespread illegal alcohol trade with Indians.

In 1832, a grand jury was empanelled to assess the problem of alcohol in Arkansas Territory. The jury attempted to invoke an outdated Spanish law that prohibited alcohol production and sale, but it could not enforce the ordinance. The emerging Arkansas middle class grew alarmed by the frequent, alcohol-fueled unrest that seemed to surround taverns. There was also a developing sense that alcohol hindered the ability of workers and craftsman to perform their jobs adequately, which some business owners feared would result in lower profits. The rising chorus against alcohol coincided with the sweeping antebellum religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening. A national temperance movement emerged in the 1820s and quickly spread to the drink-sodden South. In Arkansas, drinking was not only an everyday fact of life but also an integral part of state politics, since candidates typically won favor with voters by providing ample amounts of whiskey on Election Day.

The organized temperance movement in Arkansas began in earnest with the formation in 1831 of the Little Rock Temperance Society, which was closely aligned with local churches. Methodists were usually the most ardent in supporting prohibition, while Baptists were not widely involved in opposing alcohol until after the Civil War. At first, Arkansas temperance advocates spoke against whiskey and other “hard” liquors while tacitly condoning beer and wine consumption. Significantly, the Little Rock Temperance Society—unlike other such organizations—allowed women to join its ranks, opening the door for greater female participation in state politics. Women eventually formed the heart of the prohibition movement in Arkansas, opposing alcohol as a threat to the family structure.

In more rustic parts of the state, alcohol consumption was essentially immune to efforts to curb its abuse. Nevertheless, William Woodruff, founder and publisher of the Arkansas Gazette, cosponsored an 1841 rally to encourage the state legislature to outlaw liquor sales. In the 1850s, the Arkansas General Assembly moved to ban the manufacture and sale of alcohol, but this measure did little to curtail consumption. Thus, while alcohol use thrived during the decade, so too did efforts to ban or limit its sale. For instance, in 1854, saloons and stills throughout Hempstead County were boarded up and closed by order of local officials. An 1855 law gave municipalities the power to ban alcohol, mandating that prospective taverns be approved by a local majority. This established a precedent that largely still exists today, as counties have been able to hold referendums on whether or not to allow alcohol to be sold within their borders.

The push for prohibition generally came from emerging urban centers such as Little Rock (Pulaski County), where residents worried that the state’s economic development would be hampered by Arkansas’s reputation as an intemperate frontier. Some of the state’s most notorious outposts known for libertine attitudes toward drink, such as Napoleon (Desha County), were subject to attacks from temperance advocates.

The Civil War brought greater efforts by state leaders to prohibit the sale of liquor. In 1862, under Confederate rule, the state government passed a statewide ban on distilleries in order to save grain for the war effort. This did little to curb backwoods “bootleg” whiskey production, and indeed, many prominent Arkansans openly ignored the law, such as Fayetteville (Washington County) judge David Walker, who proclaimed that he would pay “any price in or out of reason” to acquire whiskey. In 1864, the state’s efforts to stop the production of alcohol fell apart when Governor Harris Flanagin signed a bill that allowed distilleries to pay the state for the right to produce alcohol. After the war, amid renewed calls for temperance, the Republican Party embraced the issue as part of a broader platform that endorsed greater government activism on social causes. In an attempt to limit election fraud, Arkansas Republicans passed legislation banning the sale of alcohol on Election Day, while making it illegal to refuse to sell alcohol on the basis of race. In many towns, African Americans were regularly denied alcohol for fear of social unrest.

In the post-war era, farmers found they could earn far greater profits by producing alcohol than by growing corn or other agricultural products. The spread of moonshine stills and the illegal trade in alcohol spurred response from Arkansas law enforcement. Throughout the 1870s, in what became known as the “moonshine wars,” federal revenue agents (who assailed moonshine as a violation of the law because it was being sold without paying the requisite liquor tax) fanned out across the hilly terrain of northern Arkansas in search of illegal stills. Raids against moonshiners (also known as “wildcatters”) were common, and stories of violent shootouts were vividly recounted in local newspapers. Local officials often sided with wildcatters in opposition to federal authorities, and jury nullification—in which accused wildcatters were given extremely light sentences or acquitted—was commonplace. In the 1890s, John Burris, a deputy revenue collector, personally closed over 150 stills and investigated hundreds more while posing as a timber buyer.

Meanwhile, in communities throughout Arkansas, women were increasingly engaged in urging saloons to close. Local chapters of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the leading national organ for alcohol reform, sprang up across the state. By the late 1880s, over 100 anti-saloon or temperance organizations existed in the state, seeking not only legislative reform but also encouraging young Arkansans to pledge to “abstain from intoxicating liquors.” The efforts of temperance proponents culminated in substantial policy reform. In 1871, the General Assembly voted to allow local referendum to decide whether saloons should be banned within three miles of colleges and schools. Eight years later, the legislature passed a law that called for towns to hold referendums every two years on whether or not to allow the sale of alcohol in quantities less than five gallons. This caused many saloons and stills to go out of business and resulted in gradual, piecemeal prohibition.

The most famous of the state’s temperance champions, Carry Nation, garnered national attention for her efforts to make prohibition a reality. While most of her career was spent outside the state, she settled in Eureka Springs (Carroll County) in 1909. Nation became famous at the turn of the century for attacking saloons in Kansas with a hatchet, and she dubbed her home in Eureka Springs “Hatchet Hall.” She had been interested in Arkansas’s prohibition movement as early as 1906, when she criticized the leniency toward alcohol exhibited by Governor Jeff Davis, whom she called “the worst governor in the Union.” Davis had, while a prosecuting attorney, called for prohibition in 1891, but once he was governor he switched sides, and out of expediency, supported the anti-prohibition movement, which in turn helped fill his campaign coffers.

The prohibition movement gained momentum in the first decade of the twentieth century as Arkansas, and indeed much of the nation, continued to ban saloons. In 1906, sixty percent of American towns had done so, and the Arkansas chapter of the Anti-Saloon League, founded in 1899, urged for more restrictions. In this period, Arkansas governors such as George Donaghey led the way for tighter control of alcohol.

Race played a role in local referendums as in 1913, when the legislature passed a bill that required petitions in support of a new saloon to be signed by a majority of white voters. In an era of widespread African-American voter disfranchisement, black opinion on alcohol was simply ignored or suppressed. By 1914, only nine Arkansas counties had managed to keep their saloons open. In 1915, the General Assembly passed the Newberry Act, effectively banning the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the state. In addition, the act failed to exempt the sale of alcohol for medicinal purposes.

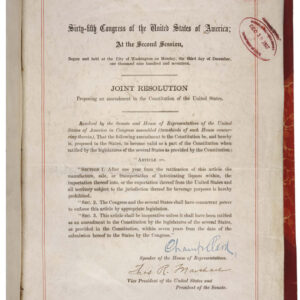

In 1916, “wets,” or those who favored loosening alcohol restrictions, managed to campaign successfully for a referendum on the issue, but efforts to repeal the Newberry Act—and restore liquor sales—failed by a two-to-one margin. Prohibitionists prevailed, in part because they appealed to prominent African Americans such as Scipio Jones, who urged black Arkansans who were able to vote to support a ban on alcohol. The following year, the legislature made Arkansas one of the first states to pass complete prohibition by outlawing the importation of alcohol. Governor Charles Brough—long a proponent of prohibition—signed the bill at the state Chamber of Commerce. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the national move toward prohibition gained the final motivation it needed, as the war effort’s demand for grain (a key ingredient for producing liquor) outweighed the need for alcohol. (Indeed, Arkansas passed its own “Bone Dry” law that same year.) As such, Congress passed the Eighteenth Amendment, which Arkansas ratified in January 1919. However, advocates for Prohibition did not stop with this success. For example, noted activist Jennie Carr Pittman remained a spirited proponent of temperance in the 1920s and 1930s.

During the 1920s, temperance formed an unlikely partnership with the resurgent Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which claimed to have over 50,000 members in Arkansas at its peak. For instance, Lulu Markwell, former president of the Arkansas chapter of the WCTU, was the Imperial Commander of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan was particularly active in the oil boomtowns of southern Arkansas, such as those in Union County, where bootleggers and gamblers openly flouted laws prohibiting such activities. In November 1922, a group of Klansmen calling themselves the “Cleanup Committee” launched attacks on liquor and gambling dens, expelling an estimated 2,000 people from the town of Smackover (Union County). By the late 1920s, the assault on liquor was subsequently taken up by Homer Adkins, sheriff of Pulaski County and later governor of Arkansas.

Joseph T. Robinson, longtime Democratic senator from Arkansas, was never a supporter of Prohibition, and he used the sweeping Democratic Party victory in the 1932 elections as an opportunity to draft legislation ending Prohibition. The onset of the Great Depression had encouraged many Americans to view repealing the ban on alcohol as economically beneficial. Indeed, by the early 1930s, the public’s mood toward alcohol had softened. With the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1933, the entire state of Arkansas was once again wet. This ushered in a new phase in the state’s history of alcohol control, in which prohibition was determined county by county. A 1935 state law mandated that, in order to hold a referendum on the matter, a petition had to be signed by at least thirty-five percent of a county’s electorate. This was a formidable hurdle to “dry” advocates, and throughout the 1930s, liquor flowed relatively freely throughout the state.

While the national prohibition movement collapsed following World War II, Arkansas temperance advocates still pushed for dry counties but also had to reconcile with Arkansans’ changing attitudes toward consumption. The business community—once stalwart dry proponents—no longer sided with the fading temperance movement. Indeed, from the late 1940s through the 1960s, dries suffered one setback after another. Winthrop Rockefeller, governor of the state during the late 1960s, argued that liquor sales would boost tourism and stimulate the economy.

By the end of the twentieth century, the lines between wet and dry counties had solidified, with forty-three counties dry and thirty-two wet. A 1993 bill essentially updated the 1935 legislation, restricting referendums on county-wide prohibition to once every four years. Yet in order to get on the ballot, thirty-eight percent of the electorate must sign a petition—a high threshold in most counties. In 2003, the state Alcohol Beverage Control Board began granting private club licenses (which gave club proprietors in dry counties the right to serve alcohol) in, among other locations, Batesville (Independence County) and Jonesboro (Craighead County). Indeed, throughout nominally dry counties, private clubs that serve alcohol proliferate, the largest number being in Benton County, prior to citizens voting that county wet in 2012. Although Governor Mike Huckabee was himself a staunch teetotaler, pleas, largely from religious organizations, for restricting the issuance of private club licenses came to no avail.

In November 2014, a ballot initiative to approve alcohol sales statewide failed, in part due to extensive advertising paid for by liquor stores neighboring dry counties. However, in the same election, Saline County and Columbia County approved the sale of alcohol, evidence that prohibition of alcohol remains a county-by-county issue in Arkansas.

Efforts to prohibit the sale and consumption of alcohol have existed throughout Arkansas’s history, from before the territorial era to the present day. The peak of the state’s prohibition movement, roughly from the 1850s through the 1920s, witnessed a confluence of disparate political forces all aiming to curb the use and abuse of alcohol. Prohibitionists came in several forms, from health and anticrime advocates to religious leaders, business owners, women, and even white supremacists. Though each of these groups came to support prohibition for different reasons, they found common ground in the belief that alcohol represented a scourge and a threat to the state of Arkansas.

For additional information:

Arkansas Woman’s Christian Temperance Union Records. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Carver, Danna K. “The History of Prohibition in Hot Spring County.” The Heritage 46 (2019): 43–49.

Combs, H. Jason. “The Wet-Dry Issue in Arkansas.” Pennsylvania Geographer 43 (September 2005): 66–94.

Dorer, Chris. “A Bootlegger’s Oasis: Central Arkansas’s Craving for Little Italy’s Prohibition-Era Concoctions.” Pulaski County Historical Review 65 (Spring 2017): 3–10.

Eaton, Herchel L. “The Moonshine War in Eastern Craighead County (Part 1).” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 30 (October 1992): 30–34.

———. “The Moonshine War in Eastern Craighead County (Conclusion).” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 31 (January 1993): 3–8.

Frith, Timothy J. “Local Option Petitions: Unconstitutional Impediments to Happy Hour in Arkansas.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 46 (Spring 2024): 377–402.

Hunt, George H. “A History of the Prohibition Movement in Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1933.

Johnson, Ben, III. John Barleycorn Must Die: The War Against Drink in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Julian, James Basil. “Prohibition Comes to Conway.” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 11 (Spring 1969): 7–13.

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Caging the Blind Tiger: Race, Class, and Family in the Battle for Prohibition in Small Town Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 71 (Spring 2012): 44–60.

Wilkerson, Jane Ann. “Little Rock’s Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, 1888 to 1903.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2009.

Brent E. Riffel

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Arkansas Wet/Dry Counties

Arkansas Wet/Dry Counties  Bootlegged Liquor

Bootlegged Liquor  Captured Still

Captured Still  Eighteenth Amendment

Eighteenth Amendment  Hatchet Hall

Hatchet Hall  Moonshine Still

Moonshine Still  Moonshine Still

Moonshine Still  Mountain Still

Mountain Still  Carrie Nation

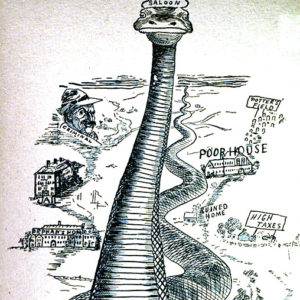

Carrie Nation  Pro-temperance Cartoon

Pro-temperance Cartoon  Prohibition Book

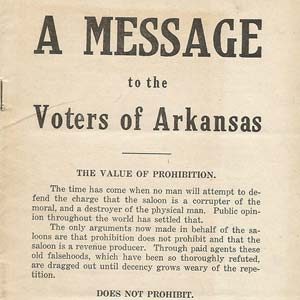

Prohibition Book  Prohibition Tag

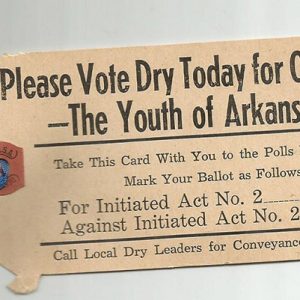

Prohibition Tag  Sheriff Destroys Booze

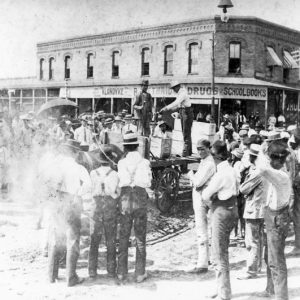

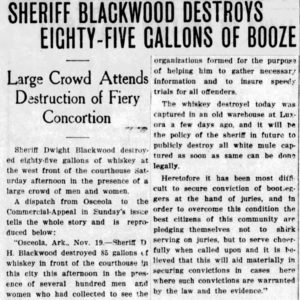

Sheriff Destroys Booze  Stone County Still

Stone County Still  WCTU Banquet

WCTU Banquet  WCTU Float

WCTU Float  WCTU Meeting

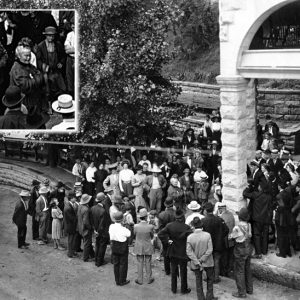

WCTU Meeting  WCTU Parade

WCTU Parade

I’d like to hear about Faulkner County and Judge Harper’s case on why it should be a dry county. I’d like to think it’s because of three colleges in the county.

My grandfather, Foster Aubrey Renfroe Sr., lived in a pair of logging camp tents in the mid-to-late 1920s with his wife, Ruby May Nelson Renfroe, and their three children [Maurice, Foster Jr. (my father, born in Lake Village, Aug. 27, 1922), and Travisteen]. Their tent home was located across from a dairy owned or operated by the Hazelbaker family near a place called Gum Corner, close to Eudora. You may also be interested in a family story. When tornados ravaged the pecan groves and homes near Lake Village just before 1930 (I think), it destroyed my grandfathers house along Lake Chicot. He and the family moved into the apartment attached to a filling station in Lake Village and ran that station for some time. The stations foundation and pump connections are still visible on a corner lot across from the NE corner of the city cemetery. Daddy tells stories about my grandfather brewing beer on that site in the shed behind the station. Dad and his older sister, Maurice, bottled the beer and capped the bottles that were then sold from the stations ice box along with the Cokes. Dad also tells about going to the main street of Lake Village one day and seeing the federal marshals smash kegs of bootleg whiskey along the sidewalks. The whiskey ran down the gutters.